A huge component to what writers of Historical Fiction do is

write about real people. That’s a huge component of what the readers are

looking for – not just the clothes and habits of a distant time, but the

flesh-and-blood beings who wore those clothes and had those habits.

One type of HF novel that take a fictional lead character

and sets him or her in real places, interweaving them into the action – Lymond,

Sharpe, Flashman, Aubrey, to name just a few stellar examples.

Then there’s the other kind, when the author takes a real

person, a person who existed in history, and breathes new life into them on the

page. Penman’s Dickon, McCullough’s Caesar, Gortner’s Isabella, Moran’s

Nefertiti all leap to mind amid a wide sea of others.

Having done both, I find the first far easier. Inserting

fictional characters with their own backstories, motives, and desires into

history is great fun, allowing them to influence real events while not needing

them to conform to someone’s facts. In those novels, real people become the

supporting cast, fixed points that my fictional ones can move around.

To me, writing a novel entirely about real people is far

more challenging. Bad enough if it’s someone obscure, largely forgotten by

history (like, say, Dante’s son Pietro). It’s even more daunting to take

someone already famous and write a tale that is at once interesting and true –

true to history, true to our perception, and true to the zeitgeist, how the

culture perceives that person.

I’ve found that writing a real person well depends greatly

upon three things: Truth, Motive, and Tone.

Truth is most often thought to be found in facts – who did

what, when. Some people are better documented than others, which is both a help

and a hindrance – more signposts to guide the story, less wiggle-room to play.

Yet facts don’t tell the story. Motive does. Because the

best stories don’t just tell us what the person did. They give us the why. And

the why should surprise us. Figuring out why historical figures did what they

did is the great joy in these kinds of novels, and I think why most of us write

and read them. It’s like being a detective, examining clues among the sources

to determine the link of events that brought Caesar to cross the Rubicon, or

Elizabeth to order the death of her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots.

To me, it’s also important to flout preconceptions. If I’m

telling the readers what they already know, why am I writing? Which brings us

not just to character motives, but the author’s as well. Take for example

Sharon Kay Penman’s portrayal of Richard III, which turns Dickon into a noble

and good man, thus flipping Shakespeare’s version on its head.

Shakespeare himself performed a similar feat with Brutus.

Until he set his quill to inking down the play Julius Caesar, Brutus lived in

Hell with Judas and Cassius, the great betrayers. But Shakespeare’s play has

revivified Marcus Brutus, redefining him for the last four hundred years as an

honorable man who did a bad thing for the right reasons. That’s the power of a

good story.

That’s also the tricky part. The author’s motives matter

just as much as the character’s. For example, when writing The Master Of

Verona, I fell in love with Cangrande della Scala, worshipping him just as much

as my lead character did. So I had to turn it around and give him feet of clay.

Because no matter how much you admire or loathe a figure from history, it’s

important to keep them human. Archetypes are not, in themselves, interesting –

look at the plays from the early English Renaissance, the Mystery Plays with

characters like Greed and Charity doing battle. Those are far less interesting

than complex and contradictory people. No one is just one thing. Which is why

Shakespeare’s plays are still read today the world over, while the Mystery Plays

have vanished entirely.

Shakespeare. Elizabeth. Mary, Queen of Scots. Theatre. I’m

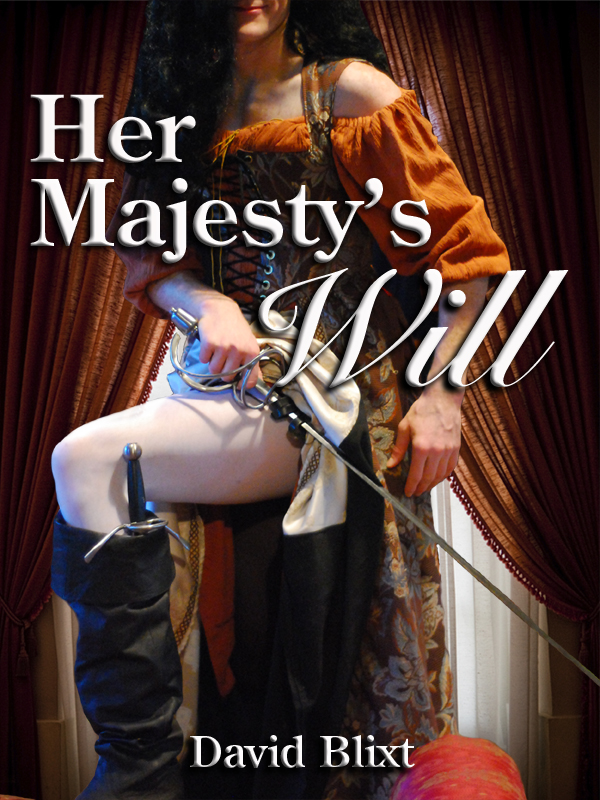

not using these examples lightly – though in Her Majesty's Will I’ve treated

them very lightly indeed. Which brings us to the final aspect of determining a

good novel – Tone.

Most often the tone of Historical Fiction is serious – This

Most often the tone of Historical Fiction is serious – This

Is What Happened. These are the novels I love. Yet there always are exceptions,

of which the Flashman novels but one brilliant example of where the author’s chief

intent is not to inform or educate, but simply to entertain.

That was my aim with Her Majesty's Will, which is a romp and

meant to be. I don’t for a second want anyone to take the novel seriously,

except as a rollicking good story. Because while I’ve contradicted no fact, I’ve

not hewed close to the probable either. This is a wonderful What-If, a

ridiculous conjecture about how Will Shakespeare came to London, before he ever

set his quill to paper, and accidentally became a spy.

Which, oddly, brings us back around to Truth. Just as in

Shakespeare’s silliest plays there are glimpses of human truths, it was my aim

to portray a Will Shakespeare who, if he didn’t exist, should have. Even if the story I tell is preposterous, I wanted to

breathe life into Will and Kit and the rest of my cast in a genuine way, giving

glimpses of the people I think they were. Or could have been. Or might have

been.

That was my Motive – through a ridiculous Tone, explore the

gaps in the Facts to expose a Truth. I’ll let you judge if I’ve succeeded. Just

know that I was smiling the whole time I wrote it.