It’s dangerous,

playing the expectations game. You rewrite Romeo

& Juliet, you’d best bring something new to the table. You write

about the fall of Jerusalem, there had better be something surprising and

uplifting in that awful story. And if you write a novel about William

Shakespeare, you’d best hope that you don’t get crushed by the weight of

expectations. Especially your own.

That was the

That was the

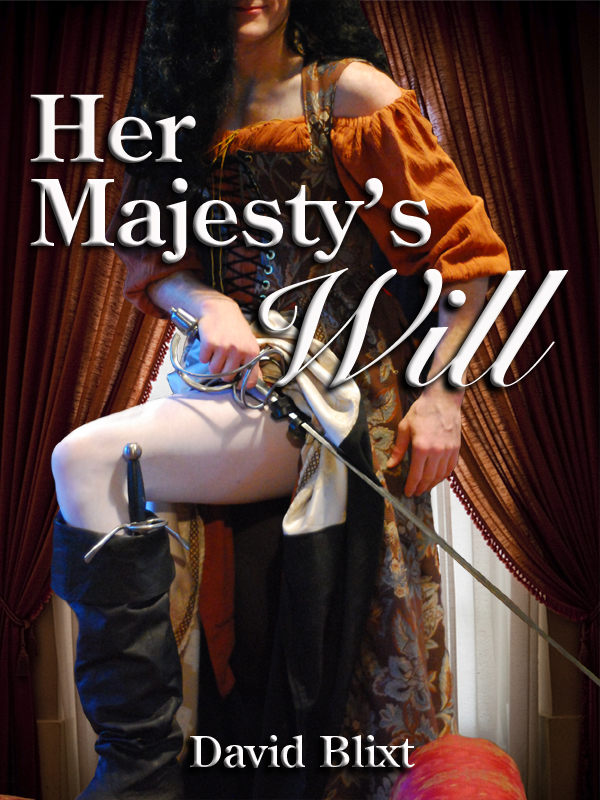

danger I was facing as I sat down to write Her

Majesty’s Will. Even though I knew it would be light-hearted and joyful,

a romp of a spy/buddy/comedy, I was still casting William Shakespeare as my

lead character. William Shakespeare! The man who invented one of every ten

words we use. The man who created more common phrases than we can count. The

man whose only rival in terms of influence is the Bible. William Shakespeare!

That’s the problem,

you see. I love Shakespeare – or rather, I love his plays. I’ve been performing

them professionally for over half my life now. I met my wife doing Shakespeare.

Last summer our six year-old son joined me onstage to do Shakespeare. Of the 36

accepted titles that bear his name, I’ve played roles in 19, so I’m just about

halfway through the canon. Through the plays, I think I’ve got a vague sense of

the man: his values, his mistrusts, his instincts, his loves, his hates, his

sense of humor, his sense of drama.

But almost all

of it is negative space. We don’t have anything even remotely resembling an autobiography,

only lines here and there that we can speculate about – Hamlet’s instructions

to the actors, Jacques’ cynical musings on life, Richard II’s thoughts on

England itself. Any of those might be the playwright’s true voice. Or they

might not. Then there are sonnets, which we might take as his own voice, if we

did not know that many of them were written on commission for other people.

Taken together,

that’s not a lot to go on. So when it came time to craft a tale with young Will

Shakespeare at the center, I had to infer a lot. Fortunately, there are themes

that emerge in his plays time and again, snippets and beats and moments that,

taken together, present a picture.

So what do I see

in Shakespeare’s plays?

– I see mistrust

of power and those who crave it. From Henry IV to Richard III, from Lear to

Macbeth, from Caesar to Antony to Octavian, Shakespeare shows how ambition is

often a snake swallowing its own tail, how desire for power leads men to evil.

How power itself is unfulfilling, yet absolute power corrupts absolutely:

BRUTUS: But 'tis a common proof

That lowliness is young ambition's ladder,

Whereto the climber-upward turns his face;

But when he once attains the utmost round,

He then unto the ladder turns his back,

Looks in the clouds, scorning the base degrees

By which he did ascend.

That formula is

as true for the Church and for Government as it is for Mankind. Power is

dangerous, as is ambition. Yet he resolutely holds out hope that man can

transcend this evil. Perhaps my favorite line from Macbeth belongs to Malcolm: Angels

are bright still, though the brightest fell.

Conclusion: Shakespeare mistrusts authority – does that mean

he’s seen the evil of authority up close?

– I see a

longing for justice. It’s in the comeuppance he gives all his evil-doers. From

Richard’s dream to Edmund’s recantation to Iago’s silence to Macbeth’s

sleep-deprived madness, the evils men do return to them. It’s almost a sense of

karma, though if that were the case, then there would not be the harm to the

innocents that also appears – Macduff’s children deserved no karmic suffering,

and poor Cinna the Poet did nothing wrong. No, Shakespeare makes it clear that

there is evil in the world, but also that God or Fate or the nature of evil

itself brings evil back to evil. Blood will have blood, as they say.

This is as true

for the Comedies as for the Tragedies. Malvolio gets a cosmic comeuppance as

he’s made the fool of by those he sought to overmaster. Yet his tormentors go

too far, and he swears he will have his revenge. At that moment, I agree with

him that they deserve it. His crime did not warrant such treatment, and shows

the danger of trying to effect justice outside the law. Shakespeare is no fan

of vigilantism, yet he understands it. And he detests arbitrary justice, as

seen in Justice Shallow in Merry Wives.

Conclusion: Shakespeare

longs for justice – because he has been wronged?

– I see his need

to side with the misunderstood. So many of Shakespeare’s best characters are

outsiders. Othello, Iago, Shylock, Aaron, Edmund, the Bastard Arthur, Richard

(thanks to his deformity) – these men are, every one, outsiders. Yes, the

majority are villains, because that’s what the audience expected, and because

villains are the ones who make a story move. But to a one, Shakespeare gives us

some of the most amazing, heartfelt defenses for who they are:

SHYLOCK: If you prick us, do we

not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not

laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you

wrong us, shall we not

revenge?

EDMUND: Why bastard? wherefore

base?

When my dimensions are as well

compact,

My mind as generous, and my shape

as true,

As honest madam's issue? Why

brand they us

With base? with baseness?

bastardy? base, base?

RICHARD: I, that am curtail'd of

this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling

nature,

Deformed, unfinish'd, sent before

my time

Into this breathing world, scarce

half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark

at me as I halt by them.

That is to say

nothing of the women, outsiders in their own right. The life he gives to

Rosalind, Viola, Kate, and Merchant’s Portia is truly astonishing. They are, in

fact, the true leads of their plays, challenging gender roles either by being

shrewish and assertive, or else by donning man’s attire and becoming men

themselves, always proving better and wiser men than the actual men around

them.

Conclusion: Shakespeare

embraces the outsider – because he is one?

– I see him

challenging his audience’s perceptions. There are obvious examples, such as

writing a Comedy and then killing everyone off (Romeo

& Juliet) or rewriting a popular play like The Taming Of A Shrew to make the female the one who “wins”

at the end (and in his version, she’s not whipped and beaten). But the one

that’s been most on my mind lately is the startling nature of his play Julius Caesar. Until 1599, Brutus was

firmly denounced as one of the great betrayers, being eternally chewed by

Lucifer in Hell, second only to Judas in terms of his crime. Shakespeare does

the unimaginable and recasts Brutus as the hero, the man who does a terrible thing

for an excellent reason, raising all sorts of moral questions, while at the

same time redefining Brutus for all time. It may not seem like much to us, but

it was a revolutionary act.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare sees the world differently from other men.

– I see the law

of unintended consequences. Nothing in Shakespeare goes according to plan. From

the death of Caesar failing to restore the Roman Republic to the secret

marriage of Romeo and Juliet failing to solve the feud (well, it does, but not

in the way the Friar intended). Tricking Benedick to fall in love with Beatrice

leads to Benedick challenging one of the tricksters to a duel. Shylock

demanding his pound of flesh ends with him impoverished and a forced convert to

Christianity. Nothing – nothing –

goes according to the plan of men.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare knew that life was unpredictable, and one must think quickly to

survive.

Above all, I see

Shakespeare’s love for the common man – the peons, the rabble, the rank and

file. Oh, as a group he disdains them – he rails at mobs at the top of Caesar, and during Mark Antony’s speech

proves how short their memories are, how quickly they can be swayed. But individually

he loves them. He certainly caters to them, pandering to their tastes with low

humor and bawdy jokes. But he also finds more good in their raw honesty than in

all the upright nobility. It is the rough, the rude, the boisterous that he

admires. Oh, they have faults, but he loves their faults along with their

virtues. Drunkenness, lewdness, cowardice, cheating, lying – these are all

accepted purely as clever means to survive in the world. He gives his greatest

wit to clowns and fools, and makes drunkards the most joyful of his creations.

Conclusion:

Shakespeare accepts and loves low men – because he came from their ranks.

So as I thought

about my Shakespeare – not the real one, but the one being created by my pen – this

is the man I saw. A fellow of common birth and uncommon thoughts. A man who

understood the vagaries of life and yet longed for justice and order. A man who

has played the villain for the best of reasons. A man quick on his feet. A man

mistrustful of authority. A man who craves the approval of his peers, even when

his nature renders him peerless. A man who has always felt on the outside,

misunderstood, different, alone.

Even before I

cracked Stephen Greenblatt’s wonderful Will

In The World, which gave me incredible historical details for

Shakespeare’s origins and contemporaries, the man himself was shaping from the

negative space created by his plays into a positive and (thankfully) very human

character.

I’ve always

maintained that Her Majesty’s Will

isn’t serious, and it’s not. Will Shakespeare and Kit Marlowe running around as

spies for Walsingham, working for the Queen? Ridiculous! I certainly wasn’t

aiming to write a biography or some serious piece of literature. This is farce.

I am the first to acknowledge that.

But just as

Shakespeare gave his best bits of wisdom to his fools and clowns, I hope that,

through my own clowning, I’ve been able to imbue my Shakespeare with something

close to Truth. If this is not who the real Shakespeare was, this is perhaps

who he should have been. A man not

dragged down by the weight of my expectations, but rather raised up by his own.