“Writing is easy. You only need to stare at a piece of blank paper until your forehead bleeds.” – Douglas Adams

When I set out to write “Her Majesty’s Will,” I was scared. Why? Because I wasn’t going to be able to rely on my usual bag of tricks. I was setting out to do something I’d never tried before. I was going to write a Comedy.

Now technically, Comedy doesn’t mean funny. In the loosest sense, it means it has a happy ending – Shakespeare always ends his Comedies with a marriage, sometimes accompanied by a song. Aristotle tells us that Tragedy is about grand things and noble people, while Comedy is about small things and ignoble people (Mel Brooks says that Comedy is about Tragic things happening to other people).

But today if you say you’re writing a Comedy, everyone expects to laugh. And when I first came up with the notion of filling in the gap of Shakespeare’s ‘Lost Years’ by making him a hapless spy, I knew I couldn’t treat it as one of my ‘serious’ novels. It was a silly idea, and had acknowledge that fact. It had to be funny.

The problem with that is, simply, I’m not funny. I’m in theatre, so I know some insanely talented funny people, and that’s not me. I have a very dry sense of humor, and I loathe most sit-coms and any movie that relies on embarrassment for a laugh. I like (some) buddy comedies, (most) screwball comedies, and anything full of wit (hello, Douglas Adams and Eddie Izzard) or ribald badinage (hello, Shakespeare and Aristophanes).

So when it came time to be funny, I went to the well of my favorite humorists to figure out the elements of what I like in a Comedy.

Not to learn.

To steal.

“Mediocre writers borrow. Great writers steal.” – T. S. Eliot

Naturally, any Comedy about William Shakespeare has to employ Shakespeare’s own comedic devices – cross-dressing, mistaken identities, disguises, musicians, mis-timings, clowns, bawds, and big reveals (if I could have added a ship-wreck, I would have!). The Bard thus gave me a mental check-list to cover. A good start. Besides, Shakespeare stole the plot for every story he ever wrote. So he couldn’t judge me for thieving.

That raised the issue of a plot. But in perfect truth, I didn’t really care about the plot. Not this time. I simply looked at a list of events during the years before Shakespeare appeared in London, and right there was the Babington Plot. Elizabeth, Mary, Walsingham, Catholics, spies, and a beer barrel? Sold!

I also knew right off the bat that this was a buddy comedy, teaming Will Shakespeare with the wily, mercurial Kit Marlowe (who really was a spy). At once I recalled my favorite books in that vein, the Myth Adventures series by Robert Asprin. I actually knew Bob back when I was a kid, and to this day I love the adventures of Aahz and Skeeve.

Of course, those books are Bob’s own homage to the Road Movies of Hope and Crosby. So the book became a Road Movie. That gave me the framework. Watching those films, I love how Hope and Crosby are always undermining the other, and through their self-interest they create their own perils. Every decision they make to save themselves only gets them in deeper. In their self-assurance and arrogance, they were their own worst enemies.

Of course, those books are Bob’s own homage to the Road Movies of Hope and Crosby. So the book became a Road Movie. That gave me the framework. Watching those films, I love how Hope and Crosby are always undermining the other, and through their self-interest they create their own perils. Every decision they make to save themselves only gets them in deeper. In their self-assurance and arrogance, they were their own worst enemies.

Where had I seen that before?

“Comedy is unusual people in real situations; farce is real people in unusual situations.” – C. M. Jones

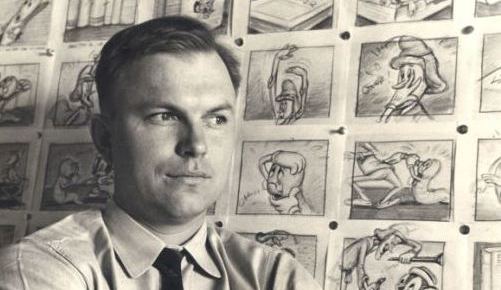

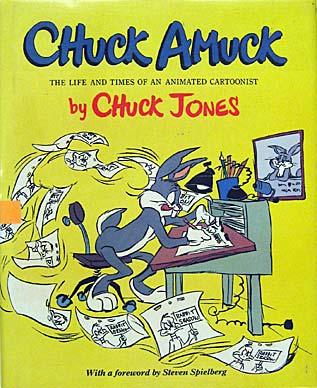

Before Shakespeare, before Aristotle, before Bob Asprin, Eddie Izzard, or Douglas Adams, I learned Comedy from one source, and one source only: Charles M. Jones.

It mortifies me to think that there might be people alive in the world who do not know his name. But all one has to do is start singing “Kill the Wabbit, Kill the Wabbit!” and everyone smiles and nods. Yeah. That’s him. One of Bugs Bunny’s creators, the inventor of Road Runner, Coyote, and Pepe le Pew, and the re-inventor of Daffy Duck. The man who gave the Grinch his Grinchy smile. That’s Chuck Jones.

Chuck had his own inspirations – Charlie Chaplin, H. L. Mencken, and Mark Twain. You can see his comic timing and commentary on humanity come from them. In marvelous, 6-minute snippets, he distilled them into pure comedic gold. I’ve watched all of Chuck’s cartoons, from his early attempts to be as cute as Disney through him slowly finding his voice to the height of his career, when he crafted the best comedic moments of the 20th Century. Because Chuck understood that comedic heroes never go looking for trouble, just react when it arrives. Moreover, he created the best buddy comedy team of all time in his pairing of Bugs and Daffy. The one is who we want to be, and the other is who we are. Or as film teacher Richard Thompson once said, “Bugs talks, and Daffy talks too much.”

Why hello, Will. Hello there, Kit.

“Writing is easy. All you have to do is cross out the wrong words.” – M. Twain

So – theme, tricks, frame, ‘plot,’ all complete. All that was lacking was the Voice.

More than any other kind of story, Comedy has a voice. On stage or in film, it’s often a literal voice, with a character looking at or talking directly to the audience. But sometimes it’s the frame of the shot, the juxtaposition of lines and action, or simply lingering an extra beat to watch a comedian react. Chuck called it a Motivated Camera, and the motivation is sharing something with the audience. Like laughter itself, Comedy is best when it’s shared.

It’s always hard to pull off. But in novels, it becomes even trickier. The true master of this was Douglas Adams, who never hesitated to use his narrative voice to be absurd and wonderful. Knowing that I am certainly no Douglas Adams, I found myself thinking, of all people, of Charles Dickens. Because while he was never absurd, he also didn’t stint from commenting upon his characters: “Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner!” Imagine the shock and sneers if some modern author described a character in such a way. But it’s a tradition stretching proudly back from Homer to story-tellers around campfires to minstrels and bards – the active voice of the narrator. Also wonderfully used in the Goofy cartoons of the early 1940s (watch “How To Ski”), as well as top and bottom of Chuck’s forgotten classic “Fin’n Catty.” So I decided to employ that same voice – arch, but never winking, and never afraid to comment on the action or the people.

Thus I was ready. Armed with the best elements of my favorite Comedies, I jumped in.

Then stopped.

Because it wasn’t funny.

“The secret to humor is surprise.” Aristotle

I was daunted. Oh, the tone was right, and the action was fine. But there was one element that I had entirely neglected, a key ingredient, the je ne sais quoi, an X-factor that kept it from singing, kept it from leaping off the page, kept it from making me want to keep writing.

So I put the story in a drawer for a couple years. I knew what I wanted, but I decided I just wasn’t funny enough to pull it off. Maybe I’d grow funnier with age – though it hadn’t happened so far.

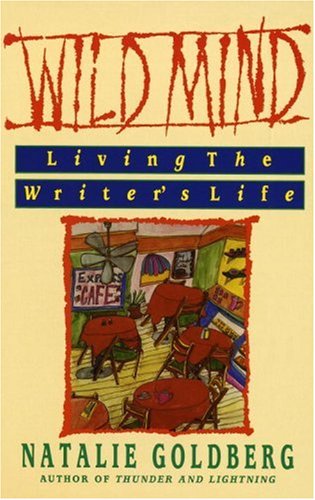

There’s a great chapter in Natalie Goldberg’s “Wild Mind” where she talks about the perils of wanting something too much. That’s happened to me in lots of auditions. I want it too badly, so I blow the audition. Whereas if I’m relaxed, if I’m myself, that’s when I tend to get cast. It’s a truth I’ve known since I was 19, but like all truths in my life, it’s one I have to keep relearning.

There’s a great chapter in Natalie Goldberg’s “Wild Mind” where she talks about the perils of wanting something too much. That’s happened to me in lots of auditions. I want it too badly, so I blow the audition. Whereas if I’m relaxed, if I’m myself, that’s when I tend to get cast. It’s a truth I’ve known since I was 19, but like all truths in my life, it’s one I have to keep relearning.

Here’s another truth, one I also forget to my peril – the answer is always in the research. That’s where inspiration lies.

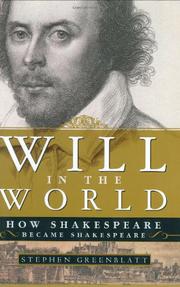

In the case of this novel, the answer was in Stephen Greenblatt’s marvelous “Will In The World,” a book not strictly about Shakespeare himself, but about the world he inhabited, extrapolating out small details from what little we know and putting them all firmly in context. It is a treasure on its own, but to me, it gave me the thing I’d been lacking, the true key to crafting the story I wanted.

I had forgotten that, more than anything else, all great Comedy has to have heart.

“Comedy is defiance. It’s a snort of contempt in the face of fear and anxiety. And it’s the laughter that allows hope to creep back on the inhale.” – Will Durst

A comic hero rises from pathos, from a desire to be understood. He also owns strong indignation at injustice. It was something Chuck knew, and wrote about frequently: “Like all heroes and heroines, Bugs Bunny grew strong when strong villains began confronting him… Bugs never engages with an opponent without reason. He is a rebel with a cause.”

In Greenblatt’s book, I saw glimpses of a potential comic hero in Will: a brilliant, frustrated, eager, disappointed, gullible, cynical, empathetic, cutting, witty, and humble young man. I know Shakespeare from his plays. But by putting him firmly in his world, he became more human. He became the mass of contradictions that we all are, that Comedy seeks to exploit. He became that rebel with a cause. With something to say.

In Greenblatt’s book, I saw glimpses of a potential comic hero in Will: a brilliant, frustrated, eager, disappointed, gullible, cynical, empathetic, cutting, witty, and humble young man. I know Shakespeare from his plays. But by putting him firmly in his world, he became more human. He became the mass of contradictions that we all are, that Comedy seeks to exploit. He became that rebel with a cause. With something to say.

Then there’s this, too: “Bugs emerges into the battle zone as a sort of cross between Groucho Marx, Dorothy Parker, James Bond, and Errol Flynn. Bugs loves the thrill of the chase. Once engaged, he is the most enthusiastic of participants: saucy, impudent, and very quick with words in circumstances that would confound most of us.” Ah, yes. That’s my man.

And Kit? Again Chuck writes: “Bugs succeeds because he is successful, but Daffy needs great determination in the fight to win the recognition he knows he deserves… A public loss of dignity will all but destroy him. The more you know Daffy, the better you like him, because you are going to recognize yourself.”

And Kit? Again Chuck writes: “Bugs succeeds because he is successful, but Daffy needs great determination in the fight to win the recognition he knows he deserves… A public loss of dignity will all but destroy him. The more you know Daffy, the better you like him, because you are going to recognize yourself.”

The secret to Comedy is humanity. If Tragedy is about rising above our frailties and foibles to be our best selves, Comedy exploits those frailties and foibles, but never maliciously. Lovingly. With empathy.

“Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long-shot.” – Charlie Chaplin

So when I finally sat down to write Her Majesty’s Will, it practically wrote itself. Standing on the shoulders of comedic giants – Twain, Mencken, Chaplin, Hope and Crosby, Adams, Asprin, Jones, and Shakespeare himself – they all reminded me that Comedy is all about us getting a happy ending we probably don’t deserve. Will gets better than he deserves in this novel. Kit absolutely gets better than he deserves. And this book turned out far better than I ever deserved.

The best part was that I was smiling the whole time I wrote it.

(One last Chuck quote: “The rules are simple. Take your work, but never yourself, seriously.” Amen, brother)