There’s been a great deal of talk about violence in media (meaning film and video-games), painting all fictional violence with a damning brush. It’s an important conversation, and one I’d like to have. But I’m not for toning down the violence in film. I’m for making it better. By which I mean, making it matter.

The trouble is not the violence. The trouble is violence without consequence.

There are many talented writers out there, writing brilliant stories. But a lot of what I see in the Action-Adventure movie world has no weight, because violence has no cost. A guy fires off a million rounds of ammo, mowing down faceless badguys. It can be visually awesome, and it’s fun to watch, and you forget it ten minutes later. It has no weight.

For me, all violence should tell a story. That story should never be easy, never be comfortable. It can be enjoyable, sure. Even better, it can be inspiring, heart-pounding, and cathartic.

Clearly I’m a fan of Shakespeare. I love his plays. And Shakespeare learned the rules of his craft from Aristotle, including the importance of catharsis, the cleansing that happens through a shared trial. As an audience, we share the hero’s trial. The greater the trial, the deeper the catharsis. That’s the theory.

Unlike Aristotle, Shakespeare never wrote down rules, or at least he didn’t pass them along to us. But reading his plays, there are some very definite rules at work:

– Instigate an act of violence, and you will receive a violent end

– There is no justification for murder. Ever.

– Justice is for the authority of King, Prince, or God, not the average man

None of this is to say that Shakespeare doesn’t have his characters flout these rules. Nor do these rules apply to warfare, where armies meet. But he is absolute in his rules for personal violence. If you commit violence, or if you take the law into your own hands, you are sowing the seeds for your own destruction.

A few examples:

– Romeo attacks Tybalt for murdering his friend, Mercutio. Though in our eyes he’s justified, he is taking the law into his own hands. And by killing Tybalt, he is dooming himself and Juliet.

– Titus Andronicus, whose sons have been murdered and his daughter raped, kills the rapists and cooks them into meat dishes to serve to their mother. Revenge is achieved, and perhaps some form of justice, but he is again placing himself in the place of authority, and dies. Unlike Romeo, he accepts this as the cost of his revenge.

– Laertes agrees to kill Hamlet in revenge for the Danish Prince murdering his father Polonius behind the arras. Laertes, of course, is cut with the same poisoned blade he used to cut Hamlet, a lovely ironic touch, mirroring the old phrase ‘when setting out for revenge, first dig two graves.’

– Brutus, the best example of all. He tries to save Rome from monarchy by killing his friend and mentor Caesar. He is clearly portrayed as a good and honorable man doing a terrible deed for the best of reasons. But motives cannot change the fact that it is still a terrible deed, and he pays the ultimate price for it.

Then there are those who are not even trying to justify their violent deeds – Macbeth, Iago, Richard – who commit acts of violence to satisfy their ambitions, their jealousies, and their rage at life. None of them live. In Shakespeare, the instigators of violence are always, always, consumed by violence.

In short, there is never violence without consequence. And that’s what’s missing today – the cost.

Making violence have meaning was much easier to achieve in a world where any gun held only one shot and most of the violence was performed with sword or dagger. In the words of Frank Miller’s Batman, ‘We kill too often because we’ve made it easy… too easy… sparing ourselves the mess and the work.’ If you’re going to kill someone with a sword or knife, there’s a certain commitment to the deed, as it will take work. What a good story-teller can do is make taking a life require an effort, re-create that commitment, and never make it casual or easy.

Here’s a modern example of violence with consequence – DIE HARD. Not the second, fourth, or fifth installments of the series, but definitely the original, and to some extent the third.

Most everyone agrees that the original DIE HARD is, if not the pinnacle of the Action genre, certainly a touchstone and model to be emulated. But what producers and writers mistakenly focus on is the set-up – one man against twelve villains in a high rise – and not what makes the film so compelling, which is the humanity of John McLane.

In DIE HARD, surviving hurts. The violence is messy, and has unintended consequences. John is so battered by the end that his wife doesn’t recognize him. He’s been shot, beaten, and had to run (or hop) across broken glass. Of course, this is Hollywood, so they didn’t go the extra mile of NOTHING LASTS FOREVER, the book upon which the film is based, and have Holly go out the window with Hans, killed by that damned wrist-watch, the symbol of her success. But at the end there is a real catharsis. John suffered to do what was hard, what was right.

That he did so with grim humor makes him more heroic. His were not James Bond-like coy tag-lines after an enemy’s death. McLane’s humor was bravado, a way to keep up a brave face against the enemy. But we also see his guard down, in that great monologue where he asks the cop outside to apologize to his wife for him. Also in that moment of pure honesty. “Please, God, don’t let me die.”

Speaking of Bond, there is a reason I enjoyed CASINO ROYALE more than any other Bond film in years, perhaps ever. I am a huge Bond fan, but have cared less and less for the films over time. I’ll still watch the original trio of Connery’s films, OHMSS, THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS and maybe GOLDENEYE. But CASINO ROYALE was a return to the Bond of Ian Fleming, the Bond of the books, the damaged, cynical man who kills for his government and who doesn’t get the girl. Twice in the books Bond fell truly in love. Both times, the woman he loved died – once by her own hand, once murdered. While the fantasy of Roger Moore’s Bond was childishly fun to watch, those films have no weight. They don’t matter the way that CASINO ROYALE and SKYFALL do. Because violence has consequences.

In contrast, there’s the movie TAKEN. I enjoyed it, and I remember how much of a badass Liam Neeson’s character was. But I don’t remember his name, or much of anything but the fighting. I remember his daughter being dragged out from under the bed. That was the only human moment in that film.

The trouble with films like TAKEN or the DIE HARD knock-offs, which try to replicate the original’s formula, is the indestructibility of the hero. Because the explosions have to be bigger, the violence bigger, there’s less and less room for humanity. And it’s humanity, not the lack of it, that makes an Action film great. Jason Bourne’s search for his identity; Aragorn’s reluctance to lead juxtaposed against his natural ability; Tony Stark’s growth from naïve weapon-maker to arrogant protector; and of course, the greatest of all Action heroes, Indiana Jones. Remember that scene in Raiders where – well, remember all the scenes in Raiders, because it’s a perfect film. But there’s no point at which the violence is easy. It can be funny and still be desperate and thrilling. The giant ball at the beginning is hilarious and very scary at the same time, while the great scene on the ship with the ‘years/mileage’ line is a perfect example of simple humanity and the cost of these adventures.

No, we’re not in the age of Shakespeare, and we don’t need or want all our heroes to die if they commit an act of violence. But we do need them to be mortal, and we need their deeds to have weight.

So, to my fellow writers, I have this simple suggestion. If you write a scene of violence, don’t make it bigger. Make it matter. Don’t make it easy, make it hard. Look to character and motivation to root the violence in the people committing it, both for villains and heroes. Because villains are rarely villains in their own mind. Make everyone the hero of their story, make the violence matter as much to them as it should, and make it as surprising and upsetting as it is in life.

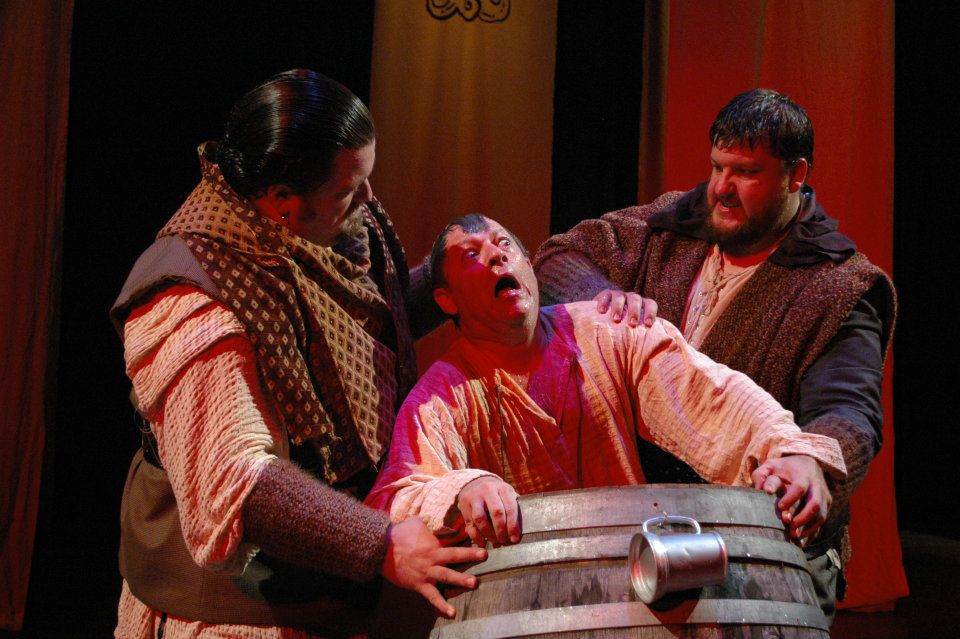

Top photo from the Michigan Shakespeare Festival’s 2012 production of Richard III, directed by Janice L Blixt.

Visit www.michiganshakespearefestival.com

Follow David on Facebook here.