Late one April evening in 2016, sitting at my desk not writing, this article in The Atlantic caught my eye. The premise was that there were more female action stars 100 years ago than today. Most were in the mold of the Perils of Pauline, with an intrepid young woman leaping off horseback or clinging to the side of a train. From the article:

“In 1914, a breakout year for the category, the actress Mary Fuller played a daring reporter in The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies. The same year, Grace Cunard appeared in Lucille Love, The Girl of Mystery, which was billed as the “Most Sensational Series of Pictures Ever Produced … AEROPLANES—LION—TIGERS—CANNIBALS—SHIPWRECKS …” Also in 1914, Pearl White, perhaps the best-remembered serial queen of all, made headlines as the fearless heiress Pauline Marvin in The Perils of Pauline, and Helen Holmes began her stint as the brave railroad telegrapher in The Hazards of Helen, which went on to become the longest-running serial, with 119 episodes over six years.”

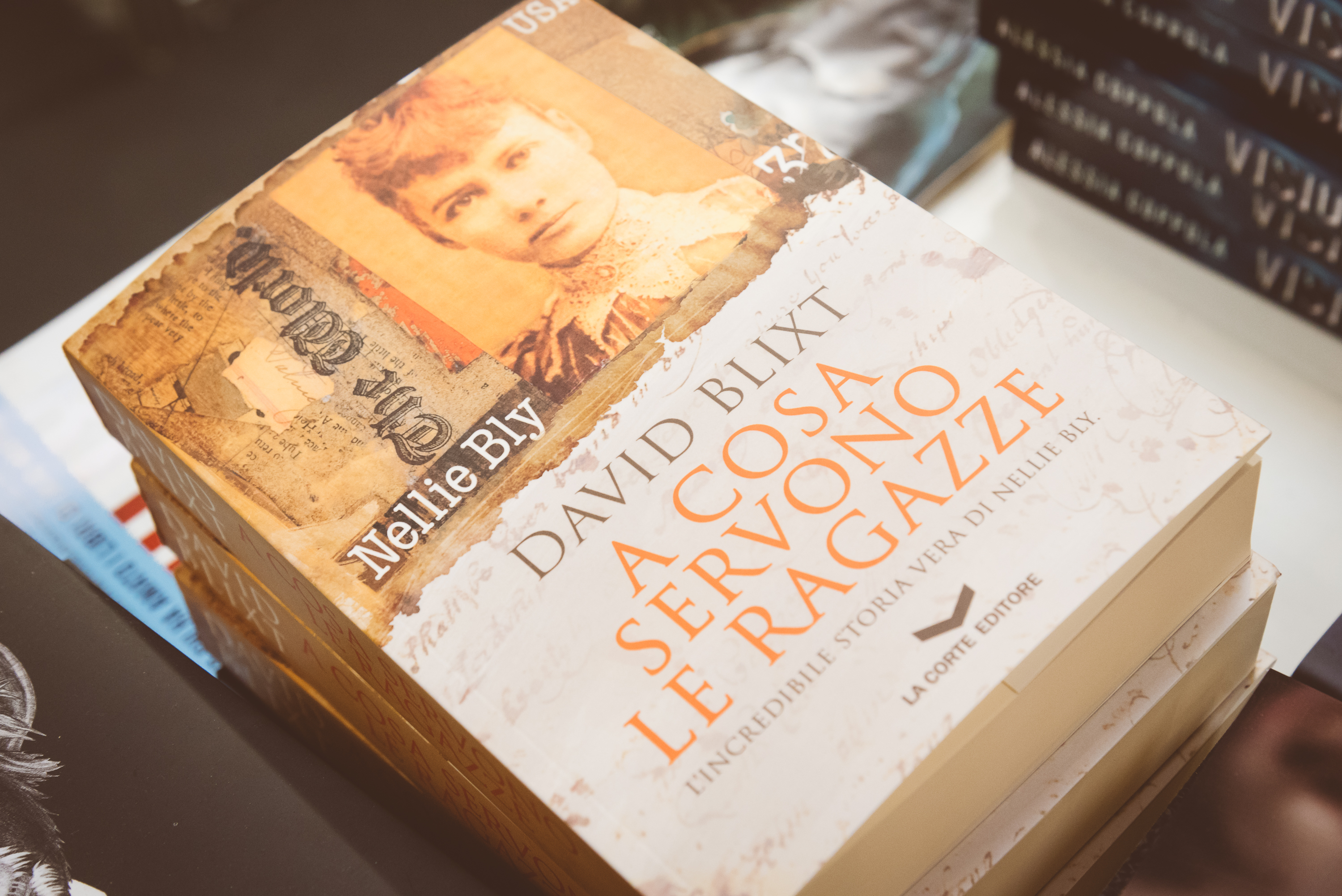

Intrigued, I started looking up these films only to discover most of the daring fictional females portrayed were newspaper reporters. Of them, the majority were based on Nellie Bly.

The name rang a very specific bell. In the second season of the television show The West Wing, the President’s amorous intentions are thwarted when he belittles the achievements of Nellie Bly, whose statue the First Lady had just unveiled. No longer in the mood, Stockard Channing gives him a short biography of Nellie, which Martin Sheen again puts down. Needless to say, the night did not work out the way he planned.

That being my sole knowledge of this intrepid reporter, I typed ‘Nellie Bly’ into The Googles and stayed up deep into the night reading, knowing I had struck gold.

Female characters drive historical fiction. My trouble has always been that the historical women who fascinate me – Cleopatra, Anne Boleyn, Boudicca, Isabella of Spain, Eleanor of Aquitaine – have all been done, and done well (I have the same problem with King Arthur stories – sure, I’d like to write one, but it’s been done). Moreover, I have a deep resistance to writing about queens or princesses. In looking for a heroine, I wanted an exceptional woman who rose from nothing to make her mark.

As a writer, I was waiting for the right woman to come along.

In Nellie Bly, I found her.

Here I had the chance to explore early Feminism, a piece of history largely ignored in the fabric of American history. If Nellie is mentioned, it’s for pioneering undercover journalism. Totally true, but hardly the whole story. It wasn’t just how she got the stories. It was the stories she chose to tell. Fought to tell. Nearly died to tell.

Most people have heard about “10 Nights In A Madhouse” or her race around the world. But there are also dozens of stories, starting right out the gate with her Factory Girls series, to her apprehending a serial rapist in Central Park and exposing a white slavery ring selling children. Her very first piece was about women who need to work to survive. Her second was about divorce. These were stories that were simply not told.

What snagged my attention was how she became a reporter in the first place. Maybe because I love origin stories, maybe because it struck me as both brave and pointed. She was responding to columnist Erasmus Wilson, who wrote under the name “The Quiet Observer”. He’d just recently penned a piece entitled “What Girls Are Good For”. Infuriated by that and by his follow-up piece responding to an “Anxious Father” who didn’t know what to do with his plain, dull daughters, 20 year old Elizabeth Cochrane wrote a scathing letter to the Pittsburg Dispatch. She signed it “Lonely Orphan Girl”.

That outraged letter prompted editor George Madden to place an advertisement in his own paper summoning the “Lonely Orphan Girl” to appear at the Dispatch offices. Filled with trepidation, she went, which directly led to him hiring Elizabeth as an investigative reporter, giving her the name Nellie Bly.

Nearly 150 years later, her outrage is still palpable. Her energy, her drive, her vanity, her vitality, her vulnerability – it’s all right there, laid bare in the pages of her stories.

Falling down a midnight internet rabbit hole, I suddenly couldn’t resist. Setting aside all plans of Star-Cross’d sequels or the long-awaited Othello novel, I dove into the research and started to write.

The result is WHAT GIRLS ARE GOOD FOR, a title I owe to Gianni La Corte. I would never have thought to repurpose Wilson’s offensive article to tell Nellie’s story.