On April Fool’s Day, 1888, undercover reporter Nellie Bly revealed her most shocking story since her escape from the madhouse on Blackwell’s Island, trapping lobbyist Edward Phelps in a bribery scandal. This is the original story that was the basis for my latest Nellie Bly novella, CLEVER GIRL (Sordelet Ink, 2020. You can download a free ebook version here). Enjoy! — David Blixt

New York World — Sunday, April 1, 1888:

THE KING OF THE LOBBY

Nellie Bly

Edward R. Phelps Caught in a Neatly Laid Trap

Nellie Bly’s Interesting Experience in Albany

How the Lobby King Contracts to Kill Bills for Cash

Dealing with Legislators as with Purchasable Chattels

Phelps Furnishes “The World” Representative with a List of Assembly Committeemen Who Are Bribable

His Agreement to Kill Assembly Bill №191 for $5,000

Afterwards Concludes to Take Less

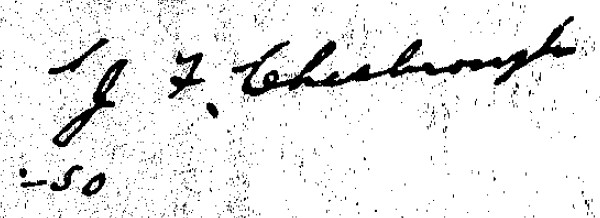

The Check to Be Made Out to His Side Partner, J.W. Chesbrough

“I Pass or Kill Any Bill”

A Revelation of Baseness Which Should Fill the State with Indignation

The Watch Here

I’m in the Lobby Ring!

Oh! what an uproarius

Jolly and glorious

Biz for a Pirate King!

I was a lobbyist last week. I went up to Albany to catch a professional briber in the act. I did so. The briber, lobbyist and boodler whom I caught was Mr. Ed. Phelps He calls himself “King of the Lobby.” I pretended that I wanted to have him help me kill a certain bill. Mr. Phelps was cautious at first and looked carefully into my record. He satisfied himself that I was honest and talked very freely for a king.

He said that he could buy up more than half the members of the Assembly. It was only a question of money. I pretended to doubt his ability to do this. To prove his strength he took out a list of members and put a lead pencil mark against those he swore he could buy. In his scoundrelly anxiety to provide his strength and to get my money he besmirched the character of many good Assemblymen.

Everybody knows Ed. Phelps, the lobbyist. He has been in trouble before, but his assurance has carried him through. During the celebrated Conkling-Platt Senatorial fight I am told that Phelps, in company with Lo Sessions, was indicted for bribing a member, who took the money up to the Speaker’s desk and exposed him.

Again, Mr. Phelps had the assurance to sue one Jones, who lives at One Hundred and Thirty-fifth street and Alexander avenue, for $5,000 on a note which Jones gave. The suit was brought in the Supreme Court here. He even tried to get the courts to sustain his wrong-doing. Jones claimed that he had given Phelps the note because the latter claimed to be able to buy certain Senators in aid of a bill. He found that the Senators were already in favor of the bill and so refused to pay. The suit was afterwards dropped, because Phelps was threatened with exposure.

But enough of Phelps. He is notorious. Anything I can say cannot blacken his character more. I can only tell what I did.

I selected a bill that I pretended to be interested in. It was Assembly bill №191. I said that if it passed it would ruin my husband’s patent-medicine business. He said he could suppress it.

The bill itself is not very interesting, but here it is:

STATE OF NEW YORK

№191, Int. 298

In Assembly

January 27, 1888

Introduced by Mr. J.W. Smith — Read twice and referred to the Committee on Public Health — Reported from said committee for the consideration of the House and committed to the Committee of the Whole — Ordered, when printed, to be recommitted to the Committee on Affairs of Clinics.

An ACT

For the better protection of the public health in relation to the sale of medicines and medicinal preparations

The People of the State of New York, represented in Senate and Assembly, do enact as follows:

SECTION 1. It shall be unlawful for any person, firm or corporation to sell, offer or advertise for sale in this State any secret or proprietary medicinal preparation or any substance, fluid or compound for use, or intended to be used, as a medicine or for medicinal purposes, unless the person, firm or corporation preparing or putting the same up for use shall first file with the State Board of Health a formula or statement under oath showing all the ingredients and compound parts of said preparation, and the exact proportion of each contained therein, which shall be of standard strength, and also the name under which it is intended to be sold. If said Board of Health shall be satisfied that said preparation or its ingredients are not detrimental to public health or calculated to deceive the public, they shall issue a certificate, under the seal of said Board, authorizing the sale of said preparation in this state, setting forth the formula under which the same is to be prepared, and stating the name under which the same is to be sold, and it shall be unlawful for any other or different article to be placed in or added to said preparation, or of a different article to be placed in or added to said preparation, or of a different degree of strength, or to sell the same under any different name than as set forth in such certificate, and there shall be paid to said State Board of Health for each certificate so stated the sum of $1 for the use of said Board.

SEC. 2 It shall be unlawful to sell, offer or advertise for sale in this state any secret or proprietary medicinal preparation of any substance, fluid or compound for use or intended to be used for medicine or for medicinal purposes, unless the bottle or other vessel containing the same shall have plainly printed upon the outside of the wrapper and label thereof, in the English language, statement of each and all of the component parts and ingredients of the same and the proportion of each contained therein, and in addition thereto the name ad place of business of the person, firm or corporation manufacturing the same, and also the words “Sale authorized by the New York State Board of Health.”

SEC. 3. Every violation of the provisions of this act shall be deemed a misdemeanor, and in addition thereto the person, firm or corporation violating the same shall forfeit the sum of $200, to be recovered by any person who will sue for the same in any court of competent jurisdiction, one-half thereof to be paid to the person bringing suit and one-half to the State Board of Health for the use of said Board.

SEC. 4. Nothing contained herein shall be construed to prohibit the sale of compounds or medicines put up by a licensed pharmacist in accordance with a physician’s prescription, delivered at the time of such sale.

SEC. 5. This act shall take effect immediately.

The Trip to Albany

Armed with this little bill and what I had learned, without confiding in any one, I took the train for Albany. The day (last Tuesday) was not bright, so I spent the time reviewing what I had learned. The only thing that amused me was my list of lucky odd numbers. It was the 27th of March, the train was an odd number, my chair was №3 and there was an odd number of passengers. Even when I reached Albany this odd streak did not desert me. I walked to Stanwix Hall and was given room №15, and there were only three chairs in the room. I did not look any further for odds.

The next day about noon I made my appearance at the Kenmore Hotel, where Mr. Phelps resides and keeps his legislative office. A half-grown boy in uniform met me at the door ad politely escorted me through the lobby of the hotel to the elevator. A number of men who sat around glanced at me curiously.

“I want to see Mr. Phelps, please,” I said as the boy started the elevator on its upward flight.

“Do you want to send your card up?” he asked. I had intended to send up a card — not Nellie Bly’s, of course — until the boy unwittingly let me know that it was possible to get in without the use of that modern passport. I immediately decided to storm his castle.

I followed Buttons along the softly carpeted halls until he stopped at a door which bore on a little china plate the number 98.

At the boy’s second knock an invitation to enter was given in a gruff voice. I stood at the half-opened door and saw a gray-haired man busily writing at a desk which occupied the center of the room.

“He’s in the other room,” he replied to Buttons’s inquiry for Mr. Phelps, without lifting his head. The boy knocked on the door which separated the two rooms, as he said, “A lady to see you Mr. Phelps.”

“Very well, show her to the other door,” was the answer, delivered in a rather smooth and not disagreeable voice.

The Meeting with Phelps

“Are you Mr. Phelps?” I asked, only to make him confess the fact.

“Yes, madam,” he replied, smiling slightly, while he offered me a chair, with the request to “please be seated.”

I sat down and looked about me. This was not what I had pictured to myself. This self-possessed, smiling man could not be the vampire I had been made to believe him. As he sat in the chair close by me with a reassuring smile on his face he did not look more than fifty-five years old. He is not a robust man, yet he is not of delicate build. He was dressed plainly, but with taste. There was nothing gaudy or loud about him, as one might imagine from his position. His hair and his side whiskers are gray. His upper lip and chin are clean shaven and he has something of the parson in his appearance.

The room in which we sat was comfortably furnished. It was apparently fitted up for an office; the only piece of furniture which looked out of place was a wardrobe which stood against the centre wall.

I thought my surest bait for this occasion was assumed innocence and a natural ignorance — not entirely assumed — as to how such affairs are conducted.

“Mr. Phelps, I came to consult you on a matter of importance,” I began nervously, as if afraid of my position. “I — I hope no one can overhear us?” and I looked at him imploringly.

Winning Her Confidence

“Oh, no, you are safe to speak here,” he assured me with a pleasant smile. He drew his chair closer to me and adjusted his glances carefully on his nose, meanwhile looking me over critically.

“I have come to see you about a bill,” I began to explain. His face lighted up a girl’s will over strawberry soda on an August day. He smiled encouragingly and rubbed his hands together gently.

“What bill is it?” he asked eagerly.

“A bill about patent medicines,” I answered. “My husband is ill and he sent me to New York from Philadelphia to place some advertisements and a friend, who also has a patent medicine told me of this bill, so I came up to see if anything could be done.”

“Have you the bill with your?” he asked in a low tone.

“Yes, my friend gave it to me when he told me about it,” I replied. He got up and walked over to the door, as if to be positive it was tightly closed. Then he came back, and taking the bill, which I held in my hand, he quickly scanned it.

“Do you think you can kill it?” I asked, with a proper amount of enthusiasm

“Oh, yes,” he responded heartily. “Never fear, I’ll have it killed.”

Excusing himself he went to the other room. When he came back he had a large ledger in his hand and a large smile on his face. He sat down and, resting the book on his knee, he ran his finger down the alphabet. He turned to a page which was filled with data of bills — a sort of a memorandum. He grew very happy after this and closed the book in order to pay all attention to the poor little lamb who had come to be fleeced.

“What made you come to me?” he asked. I hardly knew what was my best reply, so I said:

“Well, I had often read of you, you know; so when my friend told me about the bill I did not want to place the advertisements and so lose all my money. If that bill passes, you know it will ruin our business.”

“That is true,” he assented warmly. “It will kill patent medicines. But who sent you to me?” he still urged.

“My friend said I might consult Mr. Phelps,” I answered evasively.

“Who is he?” he asked sharply.

“I would not like to give his name without his authority,” I said, while I wondered what I would do if he pressed the subject.

“I only wanted to know, because we have had lots of people up here paying to have that bill killed. Do you know Pierce of Buffalo? He is trying to get it killed,” he said.

“I never heard of the bill until recently,” which was true. “I concluded not to go home, so I telegraphed my husband and came on here.”

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Philadelphia. We make a patent medicine there but it sells all over New York state. Do you think you can kill the bill?”

It Will Take Money

“Oh yes; I assure you of that. Now you keep up your nerve,” he said, seeing my assumed nervousness. “I’ll kill that bill. It will take money, you know.”

It was a shock, this cool assertion. I clutched at my umbrella.

“I am willing to pay anything up to $3,000,” I said faintly, “if you assure me it will be stopped.”

“I can assure you that,” he replied confidently. “Of course, you don’t need to talk of $3,000. You see there will be my expenses, and then I will have to pay some Assemblymen.”

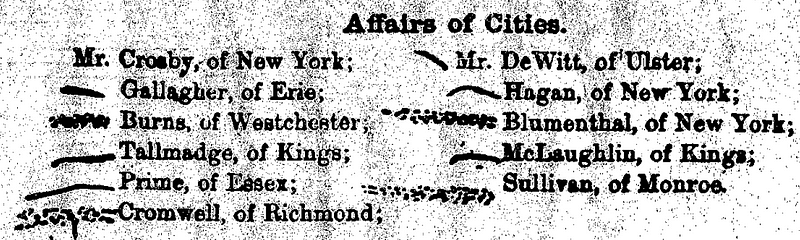

He went to the end of the room and took from there some pages containing the names and classifications of Assemblymen and Senators — a list of committees. Under the title of “Affairs of Cities” he showed me the twelve names of the men who he said would kill or save the bill.

“Mr. Crosby,” of New York, is a rich man and can’t be bought, he said calmly. “But we can buy Gallagher, of Erie, Tallmadge, of Kings; Prime, of Essex; DeWitt, of Ulster; Hagan, of New York, and McLaughlin, of Kings. The rest are no good.”

Oh, Mr. Phelps, I thought sadly, you are into the trap with both feet, for he had marked with his lead pencil the names as he read them off.

“But if the rest are opposed?” I urged quietly.

“The majority gains,” he said sweetly. “There are six out of eleven I can buy.”

“How much will it take for them?” I asked, innocently.

“You can get the lot for $1,000.”

Great goodness! just imagine, the whole lot for $1,000!

“I must never be known as connected with this,” I began to cry. “It frightens me. I wouldn’t have it known for anything; though,” I added, “I’m willing to pay all it may cost to have the bill killed.”

“That is nothing,” he said lightly. “That’s my business. I just stay here to watch bills for railroad presidents, insurance companies, &c. I’m kept here just to do this,” he said firmly. “There is a lawyer of the name of Batch in New York who is also assisting me in getting people who want to fight the same bill you are here about. I’ve had my agents send out hundreds of copies of it.”

She Came to the Right Man

I felt inclined to ask if it were to bleed the public, but I was afraid. I had not finished yet, so I said, “I thought when I came up that I would go to see Mr. J.W. Smith, who introduced the bill, but I did not know where to find him, so I came direct to you.”

“It’s a good thing you did,” he said warmly. I wondered if he would feel so sure of that in a few days. “Smith is a dissipated and unprincipled fellow. He would have taken your money and given you no returns. You came just to the right one to help you this time.”

“You are sure then for about $3,000 — which I would rather spend this way than lose it in advertising — you can kill the bill?”

“I can have it killed for that amount or near it,” he replied confidently. “Now, where can I see you again to make final arrangements?”

“Any place you state,” I replied.

“Well, when you come from Philadelphia could you come Friday. Well, you telegraph me to meet you at your hotel in New York. Where do you stop?”

“Sometimes at the Sturtevant and again at the Gilsey,” I answered. “But then I dread exposure in this affair. Could you not appoint a place where it would attract less attention? Have you no place I could see you?”

“You might come to my office,” he said, falling easily into the trap I had laid for him. That’s where, of all place, I wanted to go, but I said with well-feigned surprise:

“Oh, you have an office in New York also?”

“Yes in the Boris Building. Do you know where that is? Well, when you cross the Cortlandt Street Ferry you cross to Broadway, and it is about two blocks below. №115, room 97. Wait, I’ll write it here for you on the bill.” And he thereupon took the bill and wrote on the margin, “E.R. Phelps, 115 Broadway, Room 97, Boris Building.”

“How very kind of you,” I said.

“Now you come down Friday; meet me there between 12 and 1. If I’m not in when you arrive wait for me. I’ll be there as soon as possible. I live out of the city. Come down prepared to make final arrangements (this meant pay the price) and I assure you I’ll kill the bill afterwards.”

“Then I can place my advertisements on Friday, on your assurance that the bill will be killed?” I asked.

“Don’t place them until you see me.” This was for fear I would resent the price after my advertisements were safely placed. “I assure you, after you see me you can safely place them. The bill will then be dead, or just as good, it will be harmless.”

Trying to Get Rid of Her

“Why stay in Albany any longer?” he asked. “Why not take the 1.30 train for New York?” It was close on to that time, and I wanted my dinner, so I told him.

“They carry an eating car,” he urged. “Take that train; it will get you in at 5 o’clock”

“That will allow me to go on to Philadelphia,” I said, apparently falling into his plans, while I had no intentions of going.

“There is no use in waiting any longer,” he urged. “You’ll be seen, and that will raise comment. You might as well go now, and be sure to meet me Friday.” I began to suspect that he feared if I remained longer some other boodler would get hold of me and rob him of his prey, or that I would discover that which I already knew, i.e., that the patent-medicine bill was really dead and had been for some time. So I promised to go.

“I’ll take that list home to show my husband,” I said, as I reached for the list he had marked of buyable assemblymen.

“Give it to me,” he exclaimed hurriedly, as he took it from my grasp. “Your husband may know some of these men and may tell them. It wouldn’t look well for me to cross off those that can be bought. I’ll cross out all the names.”

The List of Honest Men

My heart sank. I really believe if hearts could faint mine fainted. Here was my only clue to those who, Mr. Phelps alleged, could be bought. If he crossed out all I could not tell one from the other. I shut my eyes and thought of several nasty things against cunning men and odd numbers. Then I opened them and looked blankly as he started to destroy my clue. He placed the sheet on a book on his desk and made crosses against the remaining names, excepting Mr. Crosby’s, and then he handed it to me. I glanced at it, and with a prayer of thanks folded it hurriedly and placed it in my purse.

The rough covering of the book had caused the lead pencil to make a peculiar spotted line against the second lot of names marked by Mr. Phelps.

When marking the original ones the committee list was on a flat, smooth surface, and as it had pens that the lines are as distinctly recognizable as though they were in difference colors.

Here is a fac-simile of the list just as he marked it:

After dining at my hotel I started for the city. I had told Mr. Phelps that the name I gave him — Miss Consul — was an assumed one, taken because my own and my husband’s name was so familiar that everybody would recognize it at once So I went under my maiden name.

As soon as I got to New York I sent a telegram to a friend in Philadelphia, instructing him to forward it from there to Mr. Phelps. It was done to ease any doubts he might have. This ran as follows:

Philadelphia, March 28.

E.R. Phelps, Room 96 Kenmore, Albany, N.Y.

Have made satisfactory arrangements with husband. Will see you as agreed.

Miss Consul

The Second Meeting

Friday came and with it the disquieting intelligence that the bill I professed to be interested in had been reported adversely by the committee on Thursday. How would Mr. Phelps act under this news? However, I borrowed a long sealskin dolman to give me a matronly look, and hiring a hansom I was driven to №135 Broadway, the Boris Building.

Mr. Phelps name was on the boor of №97, and before I could knock the door was opened, and he, smiling sweetly, stood before me and invited me in. “My son,” he said, introducing a rather handsome young man who sat behind the solitary desk the office contained. I was wondering how Mr. Phelps knew I was at the door, when I glanced out and saw that from his window he could see everybody who came up on the elevator. The door of the office was darkened.

“I suppose you know about the bill?” he inquired sharply.

“Oh, no,” I said, in assumed voice of alarm and ignorance. “Can’t it be killed?”

“Yes, that’s it,” he said smiling, “it has been killed.”

“So soon. How clever you must be!” I remarked flatteringly.

“Well, I saw that you were anxious to kill the bill and I told you that it should be killed. It’s done. That will never bother you again.” Mr. Phelps’s son here took his silk hat and left the room.

“How did you ever manage it?” I asked simply, with a world of admiration in my eyes.

How Clever Mr. Phelps Was

“Why, you see” — he talked in a confiding whisper — ”I went to work on it right away. You see I had it transferred from the committee that first had it. As I told you, Mr. Crosby could not be bought, and I knew he and some others determined to pass it, so I went to the ones I told you I could get and told them I wanted that bill killed. They said they were anxious to get rid of it, so I had it reported back to the Committee on Public Health. I knew I could get them easier.”

“Oh, how very clever!” I breathed rapturously, “and they did not refuse?”

“No, they asked me what it was worth,” he said boldly, “and I told the $1,000, and so they promised to do it.”

“They did not dare refuse,” I murmured again.

“No; I should say they did not,” he said laughingly. “You see that’s my business. I’m the head of the Lobby.”

Oh, indeed! What a good thing I went to you. How can you ever do all the work?”

“Why, I keep a lot of runners who watch and know everything that happens I am head. They report to me, and I have books in my rooms where entries are made of every bill and notes of every incident connected with it. You noticed when you gave me the bill in the Kenmore I went into another room and got a large book? Well, by that book I at once saw all about the bill and knew just what to say to you.”

“What did you say to the committee about the bill?” I asked, curiously.

“I just told them the bill had to be killed, and I told them it was worth $1,000. I had to give my check for it right off, but I told you that I could have it done for $1,000 for the committee, with my expenses extra.

“My husband could not understand how you could buy the whole committee for $1,000. It seems so little,” I suggested.

“I couldn’t if that was my only case, but you see this is my business. I spend all my time at it. I pay these men heavily on other bills, so that makes some bills more moderate.”

“Then you can have any bill killed?”

He Owns the House

“I have control of the House and can pass or kill any bill that so pleases me,” was Mr. Phelps’s astounding reply.

“Next week,” he continued, “I am going to pass some bills and I’ll get $10,000 for it. I often get that and more to pass or kill a bill.”

I was stricken dumb. I did not know what to say. The brazen effrontery of this appalled me.

“You can take this,” handing me the Albany Journal, “to show your husband that the bill was killed. You will also see an account of it in today’s world.”

“I would like you to tell me who sent you to me,” continued Mr. Phelps. “Not that I want to pry into your affairs, but it may be one of my agents and I want to pay him.”

The only agent had been my own sweet self, so I demurred and said I feared to give the name without the man’s authority.

“I have to pay the money for killing the bill to the committee this week,” Mr. Phelps began, returning to the subject of money, “and as I got it done so quickly I thought I would deal honestly with you and only charge you $250 for my expenses. That will make a total of $1,250. Could you write a check here for that amount?” he asked boldly.

Fencing About the Money

“I — oh, dear, I’m dreadfully frightened,” I exclaimed, to give myself time to think. He smiled, as if well pleased. “You see, my husband told me not to do anything that would connect me with this affair.” I breathed easier. “For that reason I do not want to give a check.”

“Well, you could write out a check payable to J.F. Chesbrough. He is a relative of mine, and it’s just the same as giving it to me; or you could make it out in my son’s name.”

“No, I don’t want it made out to Phelps, I’m afraid,” I said; “but if you send your son up to the St. James Hotel, where I am stopping, I will give it to him there.”

“That will do,” he said carelessly, and then he called “Johnny! Johnny!”

“Aha! Johnny is waiting on the outside,” I thought, and comes at the call when the poor lamb is fleeced. I began to fear that really, somehow, they would compel me to pay the money.

“I’d rather make out a check,” I began, hastily.

“Very well, I’ll write the name for you,” and suiting the action to the word he took from his desk a white envelope, smaller than the ordinary envelope, and made the check payable to. He then wrote in the corner the amount, $1,250.

“My son will go up with you and get the check,” he said, and again began to call “Johnny.”

“Oh, then I might just as well get the money and hand it to him,” in half hopes of getting him to abandon the idea of sending someone with me. I wanted a chance to escape. He took the envelope from me and tore the ends and back off it. I wanted to save that name, so I said quickly: “Give me that, I’ll write the check after all and give it to your son.”

He handed it back. The name was yet clear, but the numbers were partially torn away, only “50” remained. Here it is:

Mr. Phelps showed me the telegram, which purported to come from me in Philadelphia, after he had called his son in to tell him to accompany me to my hotel.

Such an Honest Little Woman

“I felt queer about you at first,” he said. “It is the most natural thing in the world for a woman to come to me for such work. First I thought it was a trap to catch me.” I looked at him and then at his son in a hurt manner. “But then I saw how innocent you were and how honest I must stay I was surprised though.”

“Well, you see, I did not know what to do,” I urged, as if I had blundered. “I was so ignorant of it all.”

Mr. Phelps, Jr., leaned on the desk and glanced at me admiringly. My cheeks began to burn and I began to long for freedom. Would I never escape them?

“Madam is going up to the St. James,” Phelps, Sr., explained to Phelps, Jr., “and you are to go with her. She will give you a check there for some work I have been doing for her.”

“Can’t you come along?” I asked Mr. Phelps, Sr. “I hate to have your son connected with this; besides I am better acquainted with you.” I was getting deeper and deeper into it and I didn’t know what to do.

“Father, you go,” urged the young man. “You might as well. You would leave the office in a half hour, anyway.”

I said I had a cab at the door, but that I would not like to be seen taking Mr. Phelps away in it. They urged, but I was firm, and at last Mr. Phelps sad his father would go up on the Elevated Railway and would get there about the same time I did.

Farewell Words

“He can wait for me in the parlor,” I began, joyously, now that I could escape. Wait for me? Well, he would wait years before I would come.

“I’ll get the money, and when I go in the parlor I will hand it to you. No one will see me there.” He could be sure, no one would ever see me give him money.

“Where will you get the money?” he asked, impudently.

“Father, that’s nothing to you, so she gets it,” the young man remarked, for which I looked my heartfelt thanks.

“In a half hour, in the parlors of the St. James Hotel?” said Mr. Phelps, as I arose to start.

“Yes,” I replied, and walked smilingly with the young man to the elevator.

“I was extremely nervous over this,” I said, half apologizing for my hesitating manner.

“You’ll get over that by the time you have had more bills to kill,” he said, encouragingly. I laughed and said that I thought I should.

I got into the cab, gave the driver instructions to go a thousand different ways and to stop at the world office, where I could write my story. He was a man who knew his business and I felt confident in a short time that I was not followed.

So far as I personally know, Mr. Phelps is still waiting my arrival in the parlor of the St. James Hotel.

— Nellie Bly