This is a complete transcription of the article “Champion Of Her Sex”, containing Nellie Bly’s interview with Susan B. Anthony, originally printed in The New York World, Feb. 2, 1896.

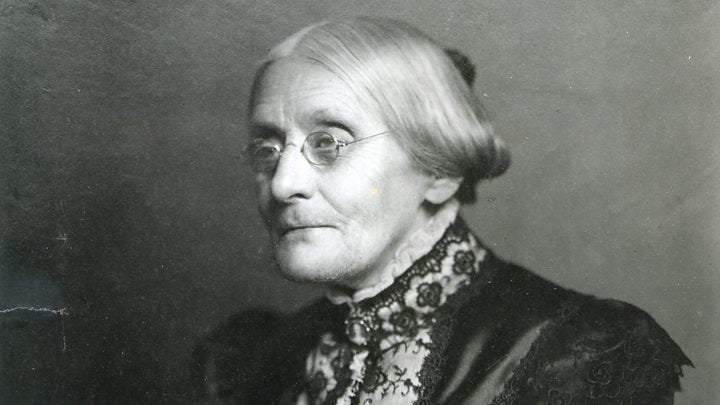

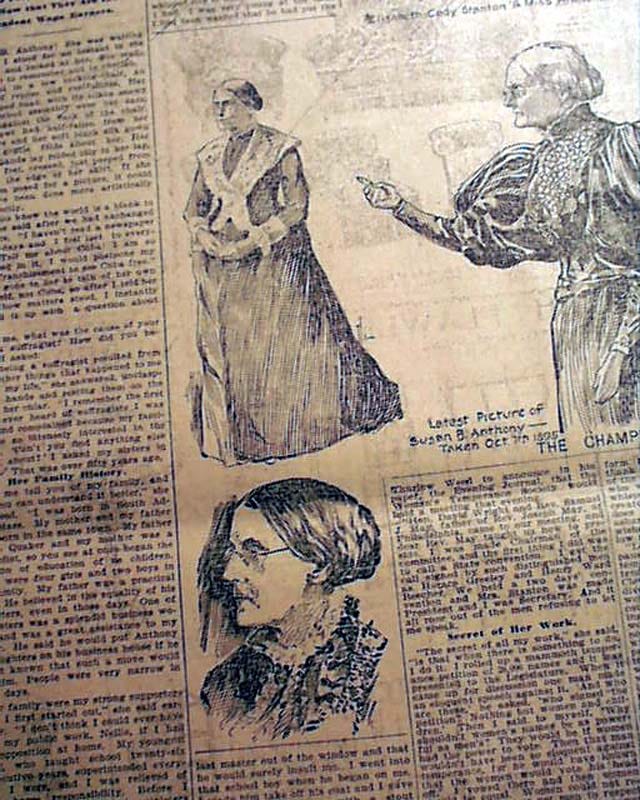

Susan B. Anthony! She was waiting for me. I stood for an instant in the doorway and looked at her. She made a picture to remember and to cherish.

She sat in a low rocking-chair, an image of repose and restfulness. Her well-shaped head, with its silken snowy hair combed smoothly over her ears, rested against the back of the chair. Her shawl had half-fallen from her shoulders and her soft black silk gown lay in gentle folds about her. Her slender hands lay folded idly in her lap, and her feet, crossed, just peeped from beneath the edge of her skirt. If she had been posed for a picture, it could not have been done more artistically or perfectly.

“Do you know the world is a blank to me,” she said after we had exchanged greetings. “I haven’t read a newspaper in ten days and I feel lost in everything. Tell me about Cube! I am so interested in it. I would postpone my own enfranchisement to see Cuba free.”

I had gone to her to talk of her own great self, not Cuba, so after I told her briefly how matters stood, I instantly followed it up with a question about herself.

“Tell me, what was the cause of your being a suffragist? How did you begin” I asked.

“My being a suffragist resulted from many other things that happened to me early in my life,” she answered, unclasping her hands and resting them on the arms of her chair. “I remember the first time I ever heard of suffragists I was bored and complained because my family were so intensely interested in the subject. ‘Can’t you find anything else to talk about?’ I asked my sisters in disgust. That was over forty years ago.”

HER FAMILY HISTORY

“Let me tell you of my family, and then you can understand it better,” she continued. “I was born in South Adams, Mass. My mother and my father were born in the same town. My father was a Quaker and my mother was a Methodist, so you see at once began the question of education of us children. There were four girls and two boys in the family. My father was a practical man. He believed in the equality of his daughters, even in those days. One of my sisters was a splendid business woman and was a great assistance to my father. He said he would put Anthony & Daughters on his business house if he hadn’t known that such a move would kill him. People were very narrow in those days.

“My family were my strong supporters when I first started out,” she said earnestly. “I don’t think I could ever have done my public work, Nellie, if I had had opposition at home. My youngest sister, who taught school twenty-six consecutive years, superintended everything I wore, and I was relieved of every home responsibility. Before I would go to a town to speak, ministers would preach against me. They would say I was a member of the Quaker Church and, while we were good people morally, we had no orthodox religion. When I went home disheartened and told my father, he would say, ‘My child, you should have thought of such a text to quite against them.’ And he could always furnish me with some text that aptly replied to my enemies.”

“But what gave you the idea of becoming a suffrage leader?” I urged.

HER FIRST IDEA OF SUFFRAGE

“Many people will tell you,” she answered, stalling, “that from their earliest days they cherished the idea that eventually became their life’s work. I won’t. As a little girl my highest ideal was to be a Quaker minister. I wanted to be inspired by God to speak in church. That was my highest ambition. My father believed in educating his girls so they could be self-supporting if necessary. In olden times there was only one avenue open to women. That was teaching. I began when I was fifteen and taught until I was thirty.

“I think the first seed for thought was planted during my early days as a teacher. I saw the injustice of paying stupid men double and treble women’s wages for teaching merely because they were men.

“But I should go back,” she added. “When I was six years old we moved from Massachusetts to Eastern New York. A company to which my father belonged owned all the down except the tavern. My father was a pattern for capitalists. The men in those days had long hours and worked until 8 in the evening. My father started a free school for them, where they were taught from 8 until 9. He also had a Bible class, where they were taught good principles and general intelligence.

“Being a Quaker, and public schools being very inferior, we always had a select school. When I was twelve years old my father made and burnt his own brick and built a splendid two-story brick house. And my mother baorded all the men engaged in the work. My father also made the woodshed two stories, and the upper floor was used for a schoolroom, where we Quaker children attended. You can know how thorough my father tried to be when he secured for our first teacher Mary Perkins, who graduated at Miss Grant’s school, in Islip, about the same time as did Mary Lyons, who founded the Holyoke Seminary.

“That laid the foundation to our education,” she continued. “You probably know enough of Quakers to know they teach of the Bible as if it were a history. Not that it is especially sacred. So you see in what a free way I was brought up.”

“Tell me about your first school,” I pleaded. “Were you frightened?”

Susan B. Anthony leaned on the arm of the chair and studied me.

USED TO THINK SHE KNEW IT ALL

“I wasn’t a bit timid,” she said frankly. “I was only fifteen, but I thought I was the wisest girl in all the world. I knew it all. No one could make me think anything else. The first time I taught was in 1835. An old Quaker lady came to our house for a teacher for her children and several of her neighbors’, making in all a class of eight. I accepted the position. I lived in her family, and for teaching their children three hours before dinner and three hours after, I got $1 a week and my board.

“After that, as I wanted to finish my own studies, I taught in the summer and went to school in the winter. And my father was the richest man in the country, too. For several terms I taught district school and boarded around among my pupils. My pay was $1.50 a week. In 1838 I gave up teaching and came to Philadelphia to a boarding-school.”

“Did you ever whip any of your scholars?” I inquired anxiously.

“Oh, my, yes!” she laughed. “I whipped lots of them. I recall one pupil I had. I was very young at the time. I had been warned that he had put the last master out the window and that he would surely insult me. I went into that school boy when he began on me. I made him take off his coat and I gave him a good whipping with a stout switch. He was twice as large as I, but he behaved after that.

“In those days,” she said, “we did not know any other way to control children. We believed in the goodness of not sparing the rod. As I got older I abolished whipping. If I couldn’t manage a child I thought it my ignorance, my lack of ability as a teacher. I always felt less the woman when I struck a blow.

“You spoke in your article the other day about the way some of our women dress,” Mrs. Anthony observed, suddenly changing the topic. “Forty-five years ago I tried to reform dress. But I gave it up. People couldn’t see a great intellect under grotesque clothes. Although I saw Horace Greeley go before an audience once with one trouser leg inside his boot and one outside!”

“For whom were you named?” I asked.

“I was named Susan after my father’s sister and after my grandmother on my mother’s side. My grandmother’s name was Susannah, but they never put that on me. When I was a young woman there came a great craze for middle initials. We girls scratched our heads to find one. The aunt who named me afterwards married a man named Brownell, and I decided to take her initials for mine. So, you see, I named myself. And I am always glad I did. There might be a thousand Susan Anthonys, but the B. makes it distinctive.

EQUAL RIGHTS WITH MEN

“Now you want to know when I first heard of woman suffrage,” she resumed. “I will tell you. In 1848 I came home at the end of my school term to visit my family. Mrs. Stanton and Mrs. Mott had just been in Rochester, and my family could talk of nothing else. I didn’t understand suffrage, but I knew I wanted equal wages with men teachers. However, I had no idea between voting and equality. I went back to my school and forgot all about it.

“In 1849 I heard Abby Kelley Foster, the Quaker Abolitionist, and I read the reports of a great convention that gave me the first clear statement of the underlying principles of woman suffrage. The next year I went to an abolition meeting at Seneca Falls where I met Mrs. Stanton, who was head of the Daughters of Temperance society. As I was a schoolma’am, I was asked to make a speech. I’ve got the yellow manuscript now of that speech. There was nothing to it. I never could think of points, and I can’t write a speech out. I must have an audience to inspire me. When I am before a house filled with people I can speak, but to save my life I couldn’t write a speech.

“A little later the Sons of Temperance held a convention at Albany, and they invited the Daughters to send delegates. I was one of the delegates. They were assembled in the hall and something was under discussion when I arose to address the Grand Worthy Master. ‘The sister will allow me to say,’ he shouted me, ‘that we invited them here to look and learn, but not to speak.’

“I instantly left the hall, and Lydia Mott, cousin of Mrs. Mott’s husband, followed me. We hired a hall, and got Thurlow Weed to announce in his paper, the Evening Journal, that the Woman’s Temperance Society would hold a meeting that evening.

“Hon. David Wright and Rev. Samuel J. May, father of Rev. Joseph May, of Philadelphia, came to our meeting, and dear Rev. May taught us how to preside. I was made Chairwoman of the committee, and the first thing I did was to call a State convention. I got the call signed by such distinguished men as Horace Greeley and Henry Ward Beecher. We held a two days’ convention and Mrs. Stanton was made President and I was Secretary. And it all rose out of the men refusing to let me speak.”

SECRET OF HER WORK

“The secret of my work,” she said, “is that when there is something to do, I do it. I rolled up a mammoth temperance petition of 28,000 names and it was presented to the Legislature. When it came up for discussion one man made an eloquent speech against it. ‘And who are these,’ he asked, ‘who signed the petition? Nothing but women and children.’ Then I said to myself, ‘Why shouldn’t women’s names be as powerful as men’s? They would be if women had the power to vote. Then that man wouldn’t have been so eloquent against temperance, for he would have known that the women would vote his head off.’ I vowed there and then women should be equal. Women could not respect themselves or get men to respect them as equal until they had the power to vote.

“In the spring of 1853 we held the first annual convention of the Daughters of Temperance. Mrs. Stanton made an address advocating the right of divorce for women whose husbands drank. It raised an awful hubbub. The prejudiced women said Mrs. Stanton was going to violate the Bible. Same old battle, don’t you see? It resulted in their saying that Mrs. Stanton was not good enough Christian to be their President. I knew if she wasn’t good enough to be their President I wasn’t good enough Christian to be their Secretary. So I resigned. ‘If Mrs. Stanton was too much of an infidel,’ I said, ‘I certainly am.’

“I want to go back to 1852 and tell you about the first convention held by the Temperance Association. We sent some delegates, but the men said that while it was good for women to be members, they could not be received as delegates because it was contrary to the teachings of St. Paul for them to speak. Nearly half the members were ministers, too. Twenty of them got up and fired away at use and then a vote was taken and we were voted down. William H. Burleigh said in his report that he hailed the Women’s Auxiliary as a valuable power to temperance. Oh! it roused the most scandalous talk. Billingsgate wasn’t in with it. The result was that Mr. Burleigh had to strike the paragraph out.

“In 1853 the Teachers’ Convention was held. By this time I had gained a little bit of public spirit, but not enough to speak. One man rose and said that men teachers were not respected as men in other professions were. He said teachers were more important than doctors, more necessary than ministers and lawyers.

“Notwithstanding all this they were never elected to high offices and were called “Miss Nancys.”

HOW SHE KNOCKED OUT A WEST POINTER

“I rose to my feet and said: ‘Mr. President!’ No woman’s voice had ever been heard in the hall before, and everybody sat dumb with amazement. The President was Prof. Davies, of West Point, and the author of several school books. He had on what was called a Websterian blue coat, with brass buttons. A very fine affair it was. He caught his thumbs under his arms and, coming to the side of the platform, said: ‘What will the lady have?’ Just as if I had fainted or something of that sort!

“I said I wanted the privilege to say a few words. Prof. Davies said that must be at the pleasure of the convention. There were about one thousand women present and about two hundred men, but it was left to the men to decide. After half an hour’s discussion on the question it was decided in my favor ,but you can imagine that then my heart was up in my throat. However, I was not going to back out then. I rose to my feet and this is what I said. I remember it word for word:

“‘Do you not see that so long as society says a woman hasn’t brains enough to be a lawyer, doctor or minister, but has ample brains to be a teacher, that every man who becomes a teacher tacitally (sic) admits before Israel and the sun that he has sunk to woman’s level?’

“Three men came down from the platform to shake hands with me and thank me for what I had done, but out of the 1,000 women there was not twenty two were not shocked. I heard them whisper all around me, ‘Who was that creature?’ ‘Do you know her?’ ‘Where does she come from?’ ‘I was so ashamed,’ said one woman, ‘that I wished the floor would open and swallow me.’

“Let me see,” Miss Anthony said, pausing. “That takes the school and temperance conventions. In 1853 I attended a woman’s rights convention in Cleveland and there I got fired up on divorce. So may women with families were supporting them on what they could earn by washing and white-washing, the only work besides teaching, for women in those days. But a wife had no right to her wages, her children, or what property she had brought into the partnership. Every thing belonged to the husband. And drunken husbands would not only collect and spend their wives’ wages, but would apprentice the little girl and boy out to the tavern-keeper and their wages would go to pay for his drink.”

DEVOTES HER LIFE TO THE CAUSE OF WOMEN

“Mrs. Stanton wrote a magnificent address on divorce, which so inspired me that I said I would burn my bridges and would devote all my life to the cause of women. But while women were the bond slaves of men, it was not use to try to do anything. I knew what ought to be done, and I had the power to get people to do it for me. I sent a call for a woman’s convention. Mrs. Stanton and Lucy Stone were there. That began my suffrage work proper.

“I had barked up the temperance tree, and I’d barked up the teachers’ tree and I couldn’t do anything. I had learned where our only hope rested. I got petitions signed for property laws and for suffrage. Until 1860 I took them in to Albany every year. Then I borrowed $50 from Wendell Phillips to pay my expenses for a canvas and I went through fifty-four counties. I had written one speech in two parts. ‘Legal Disabilities of Women’ and ‘Political Disabilities of Women,’ and I charged a York shilling (12 1/2 cents) admission. When I was through I had paid expenses and had saved $100 dollars. I sent Wendell Phillips the $50 I borrowed, but he returned it, saying I had well earned it.

“In 1860 we got the Legislature to pass a law making equal the right of guardianship of parents, giving a woman the entire right to the money she earned outside her home and, if her husband died and left little children, giving her the possession of all property and control of the children until the youngest became of age.

“When we gained all this we were the happiest mortals you ever saw. Then the war broke out and we thought it selfish to go on with our work during the time. But while we rested the lawyers had our property law repealed. In 1866 we banded together again and ever since we have been gaining steadily.”

“Do you ever lose hope?” I asked the little silvery-haired warrior.

“Never!” she answered stoutly. “I know God never made a woman to be bossed by a man. You know Lincoln said, ‘God never made a man good enough to govern other men without their consent.’ I say, ‘God never made a man good enough to govern any woman without her consent.’”

“What do you think of women promising to obey?”

“It was not to my liking,” Miss Anthony said, smiling; “but it is different to-day. Women say, ‘I take him to love, but not as my master — to obey.’ That is fair and equal.”

“What is the main thing the suffrage association is trying to get now?” I asked.

BATTLING FOR THE 16TH AMENDMENT

“The Sixteenth amendment: ‘Citizens right to vote shall not be denied on account of sex,’” was her reply.

“What is your greatest ambition now?”

“Oh, my!” with a laugh. “The right to vote. Not that I care for myself, but I want to see discrimination against women killed. We have three States in which women have the right now to vote, and we hope before ’97 to have Oregon, and Nevada and perhaps California.

“I understand,” she added with quick thought, “that Brown, of Utah, is opposed to woman’s rights. If he is, and he dares to peep, we’ll never come down to Washington again.

“You know that the law says that only idiots, lunatics and criminals shall be denied the right to vote. So you see with whom all women are classed.”

“Do you expect to see women enfranchised?”

“Yes; if I live four years longer, I expect to see it. A tidal wave will sweep us right over. It it may sweep us back. Our work is exactly like the tide of the ocean. We are swept forward and back.”

“Are you superstitious, Miss Anthony?” I asked, for I adore the little peculiarities of people.

“No; never!” she declared, laughing. “But,” she added slyly, “I never see the new moon that I don’t stop to notice whether I see it over the right or left shoulder. Not that I believe it alters anything. And I never start away on Friday that I don’t think of it. Still, I do not change the time of my departure because it is Friday.”

“Are you afraid of death?”

“I don’t know anything about Heaven or hell,” she answered, “or whether I will ever meet my friends again or not. But as no particle of matter is ever lost, I have a feeling that no particle of mind is ever lost. The thought doesn’t bother me. I feel that nothing is lost and that the hereafter will be managed as this life is managed now.”

“Then you don’t find life tiresome?”

“Oh, mercy, no! I don’t want to die just as long as I can work. The minute I can’t, I want to go. I dread the thought of being enfeebled. I find the older I get the greater power I have to help the world. I feel like a snowball — the further I am rolled the more I gain. When my powers begin to lessen, I want to go. But,” she added, significantly, “I’ll have to take it as it comes. I’m just as much in the hands of eternity now as when the breath goes out of my body.”

SOME IDEAS ON PRAYER AND MARRIAGE

“Do you pray?”

“I pray every single second of my life. I never get on my knees or anything like that, but I pray with my work. My prayer is to lift women to equality with men. Work and worship are one with me. I know there is no God of the universe made happy by my getting down on my knees and calling him ‘great.’

“True marriage, the real marriage of soul, when two people take each other on terms of perfect equality, without the desire to control the other, to make the other subservient, it is a beautiful thing. It is the truest and highest state of life. But for a woman to marry a man for support is a demoralizing condition. And for a man to marry a woman merely because she has a beautiful figure or face is degradation.”

“Do you think women should propose?”

“Yes!” very decidedly. “If she can see a man she can love. She has the right to propose to-day that she did not have some years ago because she has become a bread winner. Once a proposal from a woman would have meant, ‘Will you please support me, sir?’ And I think woman will make better choices than man. She’ll know quicker what man will suit her and whether he loves her and she loves him. But what strange marriages people make! That matter of love is beyond the ken of mortal. The different classes of minds that get together and marry! All their friends know they are not suited and can never get on together before they marry, but they never suspect it and go blindly on to their fate. It beats me!”

FLOWERS, MUSIC, ART AND POETRY

“Do you like flowers? I asked, leading her into another channel.

“I like roses first and pinks second, and nothing else after.” Miss Anthony laughed. “I don’t call anything a flower that hasn’t a sweet perfume.”

“What is your favorite hymn or ballad?”

“The dickens!” she exclaimed, merrily. “I don’t know. I can’t tell one tune from another. I know there is such a thing as ‘Sweet By and By’ and ‘Old Hundred,’ but if I heard them I couldn’t tell them apart. All music sounds alike to me, but still if there is the slightest discord it hurts me.

“Neither do I know anything about art,” she continued, “yet again when I go into a room filled with pictures my friends say I invariably pick out the best. I have grand company, I always say, in my musical ignorance. Wendell Phillips cannot tell one tune from another. Neither could Anna Dickenson.”

“What’s your favorite motto, or have you one?”

“For the last thirty years I have written in all albums, ‘Perfect equality of rights for women, civil or political.’ There is another, one of Charles Summers: ‘Equal rights for all.’ I never write sentimental things. There isn’t much sentiment in me. Neither can I read poetry. I cannot make it jingle. I suspect that is also due to my lack of musical ability.”

DRESS REFORM AND BICYCLING

“What do you think of dress reform?”

“I think the newer and better woman, the self-helpful and self-reliant woman, needs clothing that is more suited to her getting about than are the fashions of to-day. I don’t indorse hideous clothes merely because they are less cumbersome, but I think woman must evolve something that will give her freedom in clothes and yet not make her an object of ridicule. Men can wear trousers and change to gowns and caps when on the Judge’s bench. I want women to exercise the same freedom. I tried the experiment of short dresses forty years ago, and it taught me one thing — you can’t carry two thoughts before the people at the same time. One or the other will suffer. And when a woman is working for a great cause she cannot afford to indulge in peculiar notions.

“Let me tell you what I think of bicycling,” Miss Anthony said, leaning forward and laying a slender hand on my arm. “I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel. It gives woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. It makes her feel as if she were independent. The moment she takes her seat she knows she can’t get into harm unless she gets off her bicycle, and away she goes, the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.”

“And bloomers?” I suggested, quietly.

“Are the proper thing for wheeling,” added Miss Anthony promptly. “It is as I have said — dress to suit the occasion. A woman doesn’t want skirts and flimsy lace to catch in the wheel. Safety, as well as modesty, demands bloomers or extremely short skirts. You know women only wear foolish articles of dress to please men’s eyes, any way.”

WHAT WILL THE NEW WOMAN BE?

“What do you think the new woman will be?”

“She’ll be free,” said Miss Anthony. “Then she’ll be whatever her best judgment wants to be. We can no more imagine what the true woman will be than we can what the true man will be. We haven’t him yet. And we won’t until women are free and equal. The present, unfair arrangement brings out the worst in man, as well as the worst in woman. And for a hundred years after we gain freedom we’ll not know what the real man and woman will be. They will constantly change for the better, as the world does. What is the best possible to-day will be childish to-morrow. I think just the same of the man. He can’t be real and great now. His absolute control develops all his autocratic powers, just as it subordinates the woman. No woman can possibly be honest so long as her position compels her to study to please a man merely because she belongs to him and knows she must suffer if she doesn’t.”

“What would you call woman’s best attribute?”

“To have great, good, common-sense. She has a great deal of uncommon-sense now, but I want her to be rounded down to a level — not to be gifted overly in one respect and lacking in others.”

“What kind of a woman do you think succeeds best?”

“The all-around woman. I have noticed women especially gifted in one respect can never make a living. We want fewer extreme characters and ones more on the level. All abilities should be cultivated, or we’ll lose them, and we are poor creatures when left with but one. It recalls to my mind what Sojourner Truth said. Sojourner Truth was as black as the ace of spades and six feet tall. She have been a slave for four years, and attending one of our conventions after the war she was called upon to speak. ‘I can’t, chill’ern,’ she said. ‘Whare the l’arnin’ ought to be is all growed up.’ That’s what becomes of our abilities that we neglect to cultivate — they grow up.”

“What (do) you think is woman’s greatest forte in life?”

“That she shall be a woman. My point is this: that she must first be a woman — free, trained, above old ideas and prejudices, and afterwards the wife and mother. The old theory of a wife and mother needing only the capacity to cook and scrub is rapidly going to the dark ages.”

“Who is the greatest woman of our age?”

“Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She is a philosopher, a statesman and a prophet. She is wonderfully gifted — more gifted than any person I ever knew, man or woman — and had she possessed the privileges of a man her fame would have been world-wide and she would have been the greatest person of her time.”

“And now,” I said, approaching a very delicate subject on tip-toes, “tell me one thing more. Were you ever in love?”

“In love?” she laughed merrily. “Bless you, Nellie, I’ve been in love a thousand times!”

“Really?” I gasped, taken aback by this startling confession.

“Yes, really!” nodding her snowy head. “But I never loved any one so much that I thought it would last. In fact I never felt I could give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper. When I was young, if a girl married poor, she became a housekeeper and a drudge. If she married wealth she became a pet and a doll. Just think, had I married at twenty, I would have been either a drudge or a doll for fifty-five years. Think of it!

“I want to add one thing,” she said. “Once men were afraid of women with ideas and a desire to vote. To-day our best suffragists are sought in marriage by the best class of men.”

APPEARANCE AND CHARACTERISTICS

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on the 15th of February, 1820. She is 5 feet 5 inches tall and weights 155 pounds. She is very well-formed, splendidly so for an elderly woman, and she is so solid that she gives the impression of being rather slender.

Unlike most suffragists, or “brainy” women for that matter, Miss Anthony is very particular about her dress. She is always gowned richly, in stlye and with most exquisite taste.

She has an abundance of jewelry given to her by admiring friends, but she wears very little. She always carries a gold watch, and it is fastened to her with a gold chain and a strong pin in the form of a dagger stuck through a crown.

She wears one ring. It is a plain narrow wedding ring, and was given to her by her friend, Dr. Clemence Lozier, when she was thought to be upon her death bed. Miss Anthony promised to wear the ring always, and she has done so.

Miss Anthony possessed wonderful health. She never has headaches or the usual trifling complaints that afflict the modern woman. In fact, there has only been one time in her life when she had a doctor, and that was during her first illness in Kansas ten years ago.

Perhaps her good health is due to the simplicity of her life. She is a very modest eater, and is absolutely temperate. She has never tasted liquor in any form.

When she is travelling (sic) she must of necessity keep late hours, but she is a very early riser.

Her home is in Rochester, N.Y., where she lives with her youngest sister, Mary Anthony. The home was left to them by their father. Two sisters are dead, but the two boys of the family, Daniel and Merritt Anthony, still live. They reside in Kansas. Miss Anthony has six nieces and five nephews and several grand nephews and nieces.

At her home Miss Anthony rises at 7 and breakfasts on fruit, grain and coffee at 7.15. In the middle of the day she has her dinner of vegetables and one meat. She drinks water with it. At 6 she has tea with fruit and crackers. The thing she loves most of all and which she has all the time on her table is orange marmalade. At home she goes to be at 10.

She loves her home and is able to support it on a little money that has been given to her. A Mrs. Jackson, of Boston, left Miss Anthony $24,000, nearly all of which she spent in preparing and publishing and placing in libraries “The Woman’s Suffrage History.” Mrs. Rachel Foster Avery, a lovely and lovable woman whose good deeds are never ending and at whose home in Philadelphia I interviewed Miss Anthony, bought an annuity for Miss Anthony that gives her a regular income of $550 a year. Mrs. Avery is Recording Secretary to the Woman’s Suffrage National Association.

In disposition Miss Anthony is very lovable. She is always good-natured and sunny tempered. Everybody loves her dearly and she never loses a friend. She has a remarkable memory and in speaking is both eloquent and witty. She keeps an audience laughing during an entire evening.

Miss Anthony enjoys a good joke and can tell one. She never fails to see the funny side of things though it be at her own expense.

Susan B. Anthony is all that is best and noblest in woman. She is ideal and if we will have in women who vote what we have in her, let us all help to promote the cause of woman suffrage.

— Nellie Bly