This is a complete transcription of the article “Nellie Bly With The Female Suffragists”, originally printed in The New York World, Jan. 26, 1896.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 25. — I pushed in the swinging door, noticing as I did that it was covered with yellow canton flannel, and stood within the Church of Our Father.

I had an instant impression of many women, standing in groups and seated in pews; a great mingling of voices in busy conversation and the flutter of yellow. I felt frightened and confused.

Then I saw very clearly a sweet, smiling face, a face so untroubled, of such happy repose, that I ceased to fear.

“Will you tell me, please,” I begun, “where I can sit so I can hear everything?”

“Are you a delegate?” she asked, kindly.

“No. I represent a newspaper,” I answered.

“What paper?” she inquired.

“The New York World,” I said.

“Oh!” she ejaculated. Then added: “Come with me. There are tables for the newspaper people down front, and I will find a place for you. You can hear and see everything there.”

I followed her down the centre aisle of the church, which inclines like a theater. Before the elevated platforms were two plain tables. Two women and two men reporters sat around one. A woman sat alone at the other. My guide touched the solitary woman on the shoulder.

“Mrs. Colby,” she said, as the woman turned. “Here is a representative of The World.”

Mrs. Colby smiled welcome and pulled out a chair for me to take. My guide, who proved to be Mrs. Jeannette M. Bradley, of Washington, smiled and left me.

Feeling quite at ease after this evidence of kindness and consideration, I very leisurely looked about me.

WHAT THE CONVENTION LOOKED LIKE

Before me was the platform. On it was a small table, evidently for the President, a little desk for the Secretary and some dozen chairs, mostly back under a projection that formed a loft for an organ. A large flag looking very strangely with only three stars on it was draped across the projection. A small palm at either side of the platform and a vase of lilies and pinks on the Secretary’s desk was the extent of the floral decorations.

Back of me the church was filled with women. Every pew was crowded, and from the slender rods fastened at the end of the pews hung, like flags of distress, limp and ragged yellow pendants. The names of the different States were printed on them, and the delegates were expected to sit where their State was indicated.

The first thing I learned was that women suffragists do not differ in one respect from women of lesser ambitions. The hour of the meeting was announced for 10 o’clock, and it was exactly 10.20 when the President, Susan B. Anthony, appeared upon the platform.

She wore a black silk dress and a white knitted shawl around her shoulders. Her head was bare, and her gray hair was parted in the middle and combed very smoothly down over her ears. Susan Anthony’s face is thin, but it shows strength in its firm chin and strong, square jaw.

From a black cloth bag she laid up on the table she took a pair of spectacles, while rubbing them with her handkerchief she stepped forward to the reporters’ table.

“Boys, boys,” she called, smiling, “I want you to look up here. I got a present this morning. Someone sent me this white shawl.”

She turned around, that they might have a good view of it, and seemed quite pleased.

But the reporters, men and women, began to beat the table with their pencils and to shout noisily:

“Red shawl! Red shawl! Red shawl!”

“Red shawl it shall be then,” Susan Anthony said to humor them.

A red cashmere shawl hung over the back of her chair, and some one told me later that the red shawl and Susan Anthony had been inseparable for years, and that it had been spoken of so often that she had finally changed for a white one, that she was wearing for the first time. I noticed she took off the white one, but later she put it on again.

This little business being attended to, the President turned to the convention by wrapping up on her table.

“Delegates will please get their seats under their respective banners,” she said. “I am late,” she added, “because the hackman said I’d get here sooner if I rode. And I rode!”

VARIOUS SORTS OF NEW WOMEN

Laura Clay, of Kentucky, daughter of Cassius M. Clay, was called upon to pray. She rose to her feet and with eyes closed prayed, but the audience remain seated.

Then the Recording Secretary, Alice Stone Blackwell, read the proceedings of the previous day. She had a cold, unsympathetic voice and wore frightful clothes. She wore a broadcloth coat of a style fully six years old. It was double-breasted, with two rows of enormous pearl buttons. And her black cashmere skirt was shocking. I never saw skirt hang worse or one more badly made. It was short and showed her common-sense shoes, which was far from inspiring to those in front. And I judged without hesitation that Alice Stone Blackwell does not believe in confining the waist or encouraging any one part of the human body to a greater development than the other.

I never could see any reason for a woman to neglect her appearance merely because she is intellectually inclined. It certainly does not show any strength of mind. I take it rather as a weakness. And in working for a cause I think it is wise to show the men that its influence does not make women any the less attractive.

Alice Stone Blackwell is an able woman mentally. She is the editor of the Woman’s Journal of Boston. In the evening Miss Blackwell put on a red silk waist and, though it was worn with the same atrocious skirt, she was so improved that I did not recognize her.

Rev. Anna H. Shaw, of Philadelphia, Vice-President-At-Large, sat on the right of the stage, watching the proceedings with smiling eyes. She is a little dumpling of a woman, filled with good nature and a quick and pleasing wit. Her clothes fit her and are refined and genteel. She wore a tailor-made suit of dark green cloth and a wee bonnet on her gray head that tied with black velvet ribbons under her double chin.

The President read letters and telegrams from different States and balanced on her toes and heels all the time she stood. At the conclusion a tall woman advanced to the front of the platform and was introduced by the President as Mrs. Emma Smith De Voe.

“She was one of my right-hand girls up in South Dakota,” Susan Anthony added, as she laid her hand fondly on Mrs. De Voe’s shoulder.

DID SHE BEGRUDGE IT TO HER HUSBAND?

Mrs. De Voe read a report, of which I only recall one sentence.

“The time and labor, if given to any other man than her husband, would bring her money.”

Susan Anthony smiled at this and made some remark to those around her.

Nothing is unimportant at this Women’s Suffrage Convention. So I beg to note that had Mrs. De Voe been a man she would not have spoken with her hat on. It was a large black hat, with plumes on it; becoming, I acknowledge, but in striving to gain rights held selfishly by men it might be well to copy some of their few good points.

After the letters were read some women rose and moved that the Secretary be instructed to write letters of greeting to all who had sent messages, and the motion was so talked over and amended, and so many got up and sat down again, that I was completely lost and gave up all attempt to track the keep track of the matter.

WOMAN PARLIAMENTARIANS

This is what I caught and I give it for what it may be worth:

“Madame President, I would like to make a motion” — “Madam President, I request that motion to be reduced to writing.” “Madam President, I would like to suggest that the matter be left to the discretion of the clubs.” (Susan Anthony whispers to women in back of her regardless of the speakers at last she turns.) “Mrs. Thompson seconded the motion — ” the President said. “That was Mrs. Marble, and not Mrs. Thompson,” corrected a woman. “Oh, that’s all right,” the President replied, unmoved. “Madame President” — “ I’ve got one more, if you’ll just wait, Miss Clay,” said the President. (Then reads letter from Mrs. Houston, Texas.)

This was followed by a woman, whose name I did not hear, reading a paper. She was very plump, was dressed in black satin, and wore a badge.

“Mrs. President and friends,” she began in a loud voice. She read of the work of a club and then finished up by saying:

“We women have a sort of fellow-feeling for those Cubans. We know what it is to have no voice; what it is to be taxed three or four times as much as men. I know women whose farms are taxed twice as much as the farms of men are joining theirs. We can sympathize with the Cubans in wanting some rights.”

The next speaker was from Michigan I gathered from one thing she said.

MICHIGAN A GREAT PLACE FOR MEN

“In Michigan married women don’t own their own clothes. They belong, with everything else, to the husband. If you live in Michigan and are going to part with your husband, try to get your good clothes out of the house first. If you don’t, they’ll help him get a new wife.

Some women said “Ah!” surprisedly, some smiled and some looked blankly indifferent, but they were mainly the ones in mourning.

Stretch your imagination and picture of man introducing a speaker and then calling attention to the pin in his scarf and telling what kind and how many he had at home. You can’t! Neither can I. That’s why I prefer a woman’s convention. It is not so humdrum. It’s spicy and unique and, heaven knows, improved. For if there is anything stupid in this world it is a political convention. I believe that’s the only kind men have to themselves.

Charlotte Perkins Stetson has a long name, a large vocabulary, a good voice, an attractive smile and magnificent thinking faculties. She hails from California.

I never remember hearing a more pleasant speaker. She certainly should be a walking delegate for the association.

She told her the Suffrage Club had been formed in California and what great progress it had made. She said after their first Congress the men on the coast declared they had no idea women were so intelligent.

As I looked at Mrs. Stetson I mourned. She has an ideal face, clear cut and poetic. She parts her hair and combs it smoothly back over her ears, which is a very becoming style for her.

But oh, how she dresses! I fear she is daft on dress reform or some other abomination. She was decidedly wider at the waist than she was below it. We did not need to be told that she was corsetless and, I fear, petticoatless! Her suit was a mud-colored cloth, the waist being low-necked and double-breasted, and the short scant skirt hung every way but prettily.

With her high-bred and dainty face, Mrs. Stetson could have preached suffrage to all men and won favor if she only dressed becomingly.

In the matter of style, men’s convention is the better off.

SUFFRAGE FINANCES

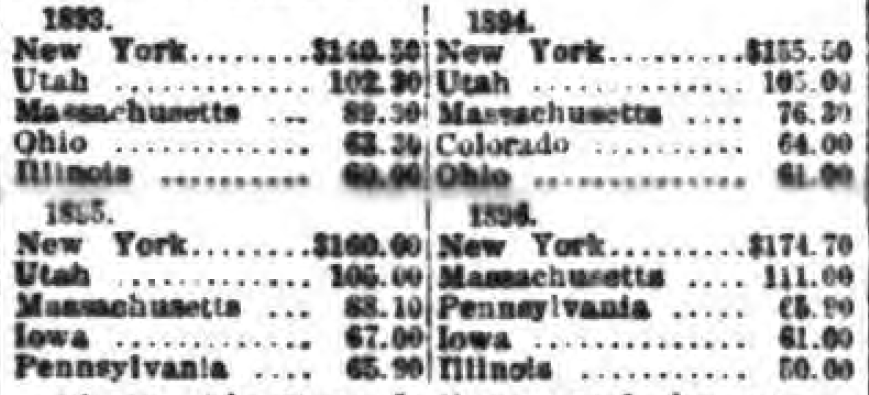

Mrs. Harriet Taylor Upton read the Treasurer’s report. She said that the National Association had paid all its debts and had $300 to the good.

“That isn’t so bad. We’re not bankrupt,” observed the President aloud.

Mrs. Upton brought a blackboard to the front of the stage, saying had a little black on it, and that it belonged to the church, and from it she read the following table, showing which five States had contributed the most money to the association:

About this time I discovered the meaning of the three stars on the woman suffrage flag. They represent Colorado, Wyoming and Utah, the three States that have granted women the right to vote.

This report brought on a heated discussion of money and how money should be sent to the National Association. The dues are 50 cents a year, and 25 cents of this belongs to the National Association.

When one hears the women talk about it being difficult to collect the dues and one realize that it is less than a cent a week, one feels that woman cannot be given suffrage too soon, or anything that will make her less the slave of poverty.

MISS ANTHONY AND THE NEW MAN

“I remember,” said Susan B Anthony, when this long and dreary discussion of money was ended, “that my father was once on a train and a man approached him and said: ‘Are you the father of Susan B. Anthony?’ He said the tables were turned. Women used to be the daughters of men, and now men were only daughters’ fathers. You all know Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt, our organization Chairman. Well Mrs. Catt’s husband is going to read a paper to us. It is the first time, I wish to add, that the husband of any of our women has appeared upon our platform. He is a specimen of the new man.”

This announcement caused great laughter and hearty applause, during which Mr. Catt stepped to the front of the stage. He is a mild-looking man, with a brown mustache and straight collar. He wore a cutaway and a four-in-hand scarf. He read a paper on the suffrage of women in Utah.

I could not see that he was one whit better, or, indeed, as good, as the majority of the women speakers. I had noted their stiffness of movement, but Mr. Catt was no better.

The President listened very attentively, and kept nodding her head in approval. Women in the audience got restless, and some moved about, whispering to each other.

The oldest woman in the audience was probably seventy-five. The youngest was five. She was in the gallery, and the desire to vote did not worry her very much. She spent her time straddling over the backs of benches, having a sort of hurdle race all to herself.

A BEQUEST TO THE ASSOCIATION

Mrs. Apton returned to say she had forgotten that Mrs. Doane, of somewhere she had forgotten, had left $1,000 to the National Association. This did not rouse any feeling of gratitude that I could perceive, though the burden of their cry had been money.

“Tell all rich women about to die to go and do likewise, only more so,” the President, dryly.

Rev. Anna Shaw showed she could think of things physical as well as spiritual by announcing a place near by where luncheon could be had for 20 cents. The announcement was received with murmurs of approval.

A call was made for Mrs. Catt, and she was found whispering to another woman. However, she was dragged up on the stage, and then had to ask what she was there for.

“I guess to know if you agree with your husband,” said the President, dryly, but another woman whispered to Mrs. Catt, who seemed at last to understand.

“This is apart from my husband,” she said. “This is my own private business.”

The matter turned out to be something about the laws governing husband and wife. Mrs. Catt suggested employing a lawyer to tell them.

It was rather interesting to know that there were women lawyers, doctors and dentists among the delegates. There were editors, one Assistant Attorney-General and one wife of a Governor, Mrs. Hughes, of Arizona. There was one colored delegate, Miss Lumkins, of Virginia. I don’t think I saw one woman there between the ages of 18 and 25.

The afternoon session was devoted to instructions and suggestions on organization. There were fewer people present than in the morning. There were two solitary men in the gallery this time and a Quaker woman. A very old man, with snowy hair, came late and walked carefully down the aisle until he found the name of the State he wish to sit under. Rev. Anna Shaw came in beaming and carrying a large bouquet of pink and white roses.

The elderly man got up and said: “Madame President,” and she replied, “Mr. Ruse!”

“I wish to suggest that it is a good thing to find out what portion of taxes are paid by women. In Philadelphia it is 33 per cent. in some wards. When this fact was told to some men they said, ‘Why, if that’s so, women should have some voicing matters.’ It strikes them every time.

CLUB TALK OF ALL SORTS

Mrs. Addison, of Kansas, rose to say that clubs could not be financial successes if they were not social successes. Rev. Shaw said so many good suggestions were made, but would be forgotten, because women had no paper or pencil. The old white-haired man rose to say that they should have a stenographer to take down everything. The colored delegate rose to ask how to select a name for a local club. Mrs. Johns said that informal meetings lead to irrelevant talk and gossip.

Dr. Cora Smith Eaton came from North Dakota. She was a very nice looking little thing and quite unassuming. She brought trouble upon herself by rising in the rear of the church to tell how the club in North Dakota had raised money.

How to get money is a topic of such absorbing interest that she was immediately called on by all the delegates to come forward to the platform and explain how the money was secured.

“The ladies of North Dakota raised it by giving a ladies’ minstrel show,” she explained, as she stood diffidently upon the platform, her hands clasped behind her. “We blackened our faces and gave a minstrel show, and oh! it was so popular! The receipts were $500, and we had $300 net. The ladies hesitated to advertise themselves, so we called it The Daughters of Ham. The part first was a minstrel show; the second part a plantation scene. It was very, very comical. In part III, we had the Highland fling, and part IV was a cake walk. Oh! it was very funny!”

Everybody roared with laughter and whispered to her neighbor.

“Madame President!” said a cold voice and in such great contrast was it to Miss Eaton’s fresh, frank tones that we all turned to look.

A woman in deep mourning was standing. Her face was grim with displeasure.

“Madam President!” she continued sternly, “do you think a minstrel show stamps us with dignity. The Woman Suffragists should not do anything that will cause reflection to be made upon them. A minstrel show is rowdyism and lowers us.”

Dr. Eaton quivered under this bitter attack, but she endeavored to rally.

“Well, that’s the question,” she said. “It brought us up, instead of lowering us.”

“Madam President!” exclaimed another woman. “I’ve known churches to do the same for money, and their dignity didn’t suffer.”

WAS IT UNLADYLIKE?

“If you got the money, that’s the main thing,” the woman in mourning agreed at last when Mrs. Rachel Foster Avery rose to say she thought minstrel shows dangerous for Women’s Suffrage clubs.

“I should be sorry to see minstrels taken up,” said another woman in black. “It hurts our dignity; but my roommate, Dr. Swift, suggested a good idea to get money.”

“We had an Australian ballot,” explained Dr. Swift in answer to the call. “We cleared over $460 net and considered we did not lose our dignity, and were instructing people in the way to vote. We voted with tickets that cost five cents a ticket, and we could vote as often as we pleased.”

This statement amused everybody, and for a few moments the church rang with laughter.

Then the woman in mourning rose again and said solemnly:

“Women suffragists must follow on cautious lines. I suggest that they devote themselves to literary and intellectual debates.”

It had grown late in the afternoon, and Mrs. Catt said that other business would be set aside, as there were some girls present to belonged to the High School and wanted to form a club of their own.

A name for the club was the first consideration. “Equal Suffrage, Jr.,” “Young Ladies’ Suffrage,” “High School Suffrage” and at last the “Young Woman’s Suffrage Club” was going to be chosen, when little Ethel Diggs said quickly:

“But the constitution says there is no distinction as to sex. How then can we call it a woman’s club?”

The “Equal Suffrage Association” was agreed upon, and the work of electing officers was going on when the woman in mourning who denounced Dr. Eaton’s minstrel show came rushing in excitedly.

“I want to let you know,” she said emphatically, “that my purse is gone. I missed it when I got to the door. It is easy to be mistaken, so I thought I would go to my hotel first to see if I had left it on my table. But I hadn’t, so I’ve come back. It is a little brown purse, and had $19 in bills and some silver in it.”

Every woman present felt for her own purse and then looked rather unpityingly upon the woman in the mourning.

“It is so easy to be mistaken,” she repeated, as if she knew where the purse was, if she only made the break to tell. “I had it here, I sat in this pew right here, and now it is gone.”

She got the janitor, and with several sympathizing women around her she went towards the door talking loudly and wholly unmindful of the interruption to the proceedings.

I have thought the day’s proceedings rather stupid, and if it had not been for the unique manner in which it had been conducted it would have had a little interest for me.

AT THE EVENING SESSION

But the evening was great. Excepting a few dreary spots, it bubbled with freshness.

The meeting was set for 8 o’clock. I got there 10 minutes after, and the church was packed to the doors. There were plenty of men present, and they seemed interested, and the women, old and young, homely and pretty, were all attention.

Charlotte Perkins Stetson had just been introduced by the President, who was looking very sweet in a black satin dress. The white silk vest in her bodice matched her snowy hair. Across her knee lay a bunch of pink and white roses.

She talked well and pleased the audience. I wonder if she can realize how much more would be her power if she dressed well!

She was telling about California.

“There is no place so good to live in,” she declared. “You come down in the morning and blow your cold fingers and look at the roses to comfort you. Our children out there get clean dirt and lots of it.

“Once,” she continued, “men in passing farm-houses would look for a clothes-line and would throw up their hats and cheer if they saw women’s clothes up on it. There are some men now who would be pleased if women didn’t wear so many clothes.”

MRS. DIGGS, OF KANSAS

Mrs. Diggs, of Kansas, who Miss Anthony called fondly “Little Annie Diggs,” spoke to refute the stories that have been printed as to the conduct of Denver women on election day. Her dress was well made and she had a pathetic little voice and her hair was dressed becomingly, so that Mrs. Diggs created a very pleasing impression. She was a good speaker, being distinct and impressive.

“I am an American citizen,” she said, “and how can I sit passively without my rights when in my veins is the same blood that was in the veins of him who cried: ‘Will win the battle or Molly Stark sleeps a widow to-night!’”

I noticed one prevailing and curious fashion followed by the women speakers. They all had lace handkerchiefs stuck under the edge of their waists. I really believe women will never be emancipated until they abolish the handkerchief from sight. It suggests tears and weakness, and to be in prominent view looks as if it were in constant demand.

Mrs. Margaret W. Kent, of Delaware, read a paper in a very wee, unemotional voice.

DELAWARE NOT SILENT

“Rather than have Delaware silent, I’ll speak,” she read. “But we’re the association’s last-born child, and you can’t expect us to have much to say. Don’t think I’m the President. I’m not. I am sorry the President is not here, and I suppose you’ll be equally sorry before I get through. We’re a conservative State. Delaware is proud of it and boast of it. Webster says conservatism is opposition to change. That’s what’s wrong with us. We have one thing to be proud of — Delaware was the first State to sign the Constitution of the United States. And it was the last to complete the link of the Women’s Suffrage Association. We are the missing link.”

Mrs. Springer, of Illinois, claimed she didn’t know that she was expected to speak, which she wanted to do from the rear of the church, but vigorous cries of “Platform!” from everywhere brought her front.

She explained how the Illinois women had gained rights through the Republicans by going to Springfield and appealing to them. She said she didn’t favor any one party, but thought it legitimate to work any of them to gain the end in view.

“I don’t think,” Miss Anthony said dryly, as Mrs. Springer left the stage, “that any of you will be able to give a Yankee guess as to Mrs. Springer’s politics.”

Mrs. Devoe began to read a paper on how to get people to attend the lectures, when Mrs. Catt stopped her.

“We had that yesterday, when you were absent,” she said.

“But I want to tell about my bonfire,” urged Mrs. Devoe. “One way to advertise a meeting after you get in a town is to follow my plan. I arrived in a town one night only to find I had not been announced. I began to wonder how Indians sent their messages. Some said by skyrockets, but they were none to be had in the town. So I built three large bonfires on three hills, and the people came in from every direction to see what was wrong. I never had a larger audience.”

“We talked about this for a full hour yesterday,” Mrs. Catt said sternly.

“I’m sorry you won’t let me tell how I do it,” said Mrs. Devoe. “Once I hired a boy with a bell to go out and cry ‘Go to the lecture!’”

But she was not encouraged to proceed, so Mrs. Reese rose, saying slowly:

“To get money you must have a large audience. When Republicans organized first in Pittsburgh they sent two men down to Wheeling, W. Va., to organize there. They held a meeting, but it was attended only by the two men, the President and Secretary. The Secretary wrote his report and said they had a large and respectable meeting. ‘I wouldn’t say that, John,’ said the President; ‘there were only our two selves here.’ ‘Well,’ says John, ‘you are large and I am respectable!’ The report was published the next night the place was crowded.”

Everybody laughed heartily at this.

Mrs. Kate R. Addison, of Kansas, is a woman Roosevelt. “We women citizens of Kansas,” she declared, “will drive the liquor element to the sea and bury it so deep it will never be heard of again. We say there should be no open saloons in Kansas. Men say they are needed. Away with such logic. Let men beware of the power they have usurped to themselves. Once it was said, ‘All things come to those who stand and wait,’ now all things come to those who stretch forth their hands and take them within their grasp.”

“These are Waterloo battles, everyone,” send Miss Anthony as Mrs. Addison made her bow. Rev. Anna Shaw nudged Miss Anthony in the back and whispered to her:

“I don’t mean Waterloo, I mean Bunker Hill,” she added hastily. “Made maybe it wasn’t Bunker Hill. Well, never mind. I never was good at history anyway.”

“Our next speaker is Elizabeth A. Yates, of Maine,” Miss Anthony continued. “There is one good woman in Maine that I know. That is Mrs. Spofford, who used to manage the Riggs House in this city.”

“Mr. Spofford managed the Riggs House,” corrected a voice.

“Oh, well, husband and wife being one,” commented Mrs. Anthony, “Mrs. Spofford manage the Riggs House.”

“I’ll stand by the desk, Aunt Susan,” Miss Yates said, “because I will have to ring myself down.”

Miss Yates is a handsome woman, after the style of Maxine Elliott, of Daly’s; only she was handsomer than Maxine. And what do you suppose? She goes to work as deliberately as a nun and kills her beauty by wearing one of those shapeless abominations called dress reform a la princesse, or something of that sort.

Her dress was a chocolate-colored satin that hung like a bag and looked worse than mud.

“I feel to-night like a Methodist minister I once knew,” announced Mrs. Mary G. Hay, of James Whitcomb Riley’s State. “A woman went to church one night and left her husband at home to attend the babies.”

Rev. Anna Shaw whispered and nudged her until at last she turned around to listen.

“It was prayer-meeting, not church, Miss Shaw says,” she continued with a laugh. “I’ll have to ‘fess’ up. She told me the story. The wife went to prayer-meeting and the man was left at home to attend the children. He wanted to read his newspaper and they were noisy, so he gave them everything he could find to keep them amused, and when his store was exhausted he took his keys and money from his pocket and gave them to the children.”

A JOKE ON THE MINISTER

“During the play the youngest child swallowed a quarter, and the father, after trying in vain to dislodge it, ran for the doctor. The doctor made an examination and looked grave. The father was much alarmed. ‘Better send for the mother,’ suggested the doctor quietly. ‘Do you think it is so serious?’ cried the poor father. ‘What church do you belong to?’ asked the doctor. ‘To the Methodist,’ reply the distracted father. ‘Then send for your minister at once. For if anyone can get your quarter out of the child that man can.’

It was very evident the jokes on ministers are relished even if given in church. Everybody laughed and seem to feel that they would give after that.

“Give liberally,” said Mrs. Hay. “Those who weren’t here last night give double. Don’t pass the hat too fast, and be sure to get them back.”

“Be sure to get them back with something in them,” added Miss Anthony.

It was rather a funny rub on the women suffragists to know that they had to borrow men’s hats to take up the collection.

A MAN SPEAKS

“It is as necessary for men that women should vote as it is for women,” he said in a deep, pleasant voice.

“Isn’t it a relief to hear a man’s voice,” whispered a little woman beside me.

I thought she was interesting, so we kept up our whispering and I found that she was there to write of the convention for the Woman’s Review, published in Ohio. She said she was on her wedding tour and that she practiced medicine two years before she married two weeks ago. Her name is Rosalie Bridewell-Goulding, and from her own story I count her a pride to women. She is a Southern girl and was very poor. She worked for the money that paid her way to college. She has supported herself and family and is a stenographer, a writer, a doctor, a part owner of the Woman’s Review, a manager of the Associated Trade Press and a suffragist.

Mrs. Colby, who sat on my left, is the editor of the Woman’s Tribune and also a member of the Women’s Suffrage Association. She has a good face and a delightful expression, but she makes her form hideous with reform dresses.

Julia B. Nelson, of Minnesota, is a love of a woman except in regard to her clothes. She dresses frightfully, though better than those who wear the shapeless rags of dress reform.

She wore a black silk with the skirt fully three inches too short, and with row after row of graduating ribbon around the bottom. Her waist was badly made and her bonnet unbecoming.

But she is so great that she can rise above all these unhappy details. However, if they were eliminated, she would be greater. If I belonged to the Suffrage Association I would propose that every club have a dressmaker who would visit New York at least once a year. Such matters sound trifling, but I know, as do all women who will confess it, that becoming and appropriate dress is most important to all women. A pretty dress will often bring back a wayward husband, and a pretty dress wins favor where “beauty unadorned” would go begging.

DRESS IS A GREAT WEAPON

Dress is a great weapon in the hands of a woman if rightly applied. It is a weapon men lack, so women should make the most of it. As their motto seems to be “use means to gain the end,” why not use the powerful means of pretty clothes?

Julia Nelson’s cheeks grow sweetly red as she speaks and her blue eyes flash and sparkle. She has a quick brain, a ready tongue and a fund of humor. She pitches her voice in a high key, along which she slides in an even monotone without a break. It is a funny voice, a funny way of speaking, and it’s fascinating.

TELLS SOME STORIES

“Men in trying to protect us,” she said, “forget that the best protection they could give women the right to protect themselves.

“There was a Justice of Peace elected to office in Maine who could not read or write,” she continued later on. “I had a friend explain his position. ‘If you see a crowd of people collecting and you think there will be trouble you can call them by saying: “In the name of the state of Maine I command you to disperse and go home,” and you can marry people.’

“Shortly afterwards the Justice visited New York for the first time, and on Broadway he saw people rushing in all directions. Thinking there was trouble, and being much alarmed by it, he got on a dry-goods box or barrel and shouted: ‘In the name of the state of Maine I command you to disperse and go home.’ But instead of dispersing two policeman came along and, thinking he was crazy or intoxicated, gathered him in. At the station-house he showed them his papers and declared himself a Justice of the Peace. ‘But you have no jurisdiction outside of Maine,’ they explained to him, and he returned home a wiser man.

Shortly afterwards a couple called on him to marry them, and after the ceremony he whispered to the bride: ‘I suppose I ought not to tell you, but I have no jurisdiction outside of Maine. This marriage is no good if you go out of the State.’”

Nellie Bly