When I found the treasure trove of novels by Nellie Bly hidden in the pages of the London Story Paper, I did not start transcribing them in their chronological order. Instead I farmed out the most legible ones to friends while reserving the hardest to discern to myself, postponing the transcribing of the middle-ground ones, neither illegible or perfectly clear.

This was fortunate, because it left her seventh novel, for the end of the queue.

I had finished nine of her novels when I started transcribing and editing Dolly. Instantly, I knew I had a problem on my hands.

By the time she wrote Dolly in early 1892, Bly had already settled firmly into her formula of breathless romantic melodrama. A headstrong woman meets her love, is parted from him, and through a series of misunderstandings, cliff-hangers, and stunning reveals, they are eventually reunited. There is always a fortune-hunting scoundrel and a scheming temptress who together work to undermine the lovers’ happiness. A maiden always attempts suicide in a body of water, and most often the villain dies a justly awful death after confessing his sins.

Since the formula was so standard, Bly attempted to entertain both her audiences and herself by changing her settings. Whether it’s picturesque Bar Harbor or a paper-box factory, the scenery forms an outer shell for the same basic story.

Unfortunately, for the setting of her seventh novel, Bly chose “the South.” Specifically, post-Civil War Virginia. Her lead character is the daughter of a wealthy Confederate general. And the novel utilizes one trope that was, at the time, at the height of her popularity — the southern “mammy,” the stereotypical formerly-enslaved Black woman charged with raising the white children of enslavers. Memorialized by Al Jolson forty years after Bly’s novel and captured in amber by Hattie McDaniel’s Academy Award-winning performance in Gone With The Wind, the “mammy” character persisted well into the 1950s on television, in film, and even in cartoons (“Mammy Two-Shoes” in Tom And Jerry).

The “mammy” was just one of several racist stereotypes to be popularized in the minstrel shows of the late 19th century. As per the norm in the history of American entertainment, what began as Black entertainers making a living was quickly appropriated by White America and fetishized. We see this over and over again, from Spirituals, to the Blues, to Swing music, to rock, to R&B, to rap. In each case, White America turns the originators of the art form to either figures of fetish or of ridicule, while profiting off of their labor.

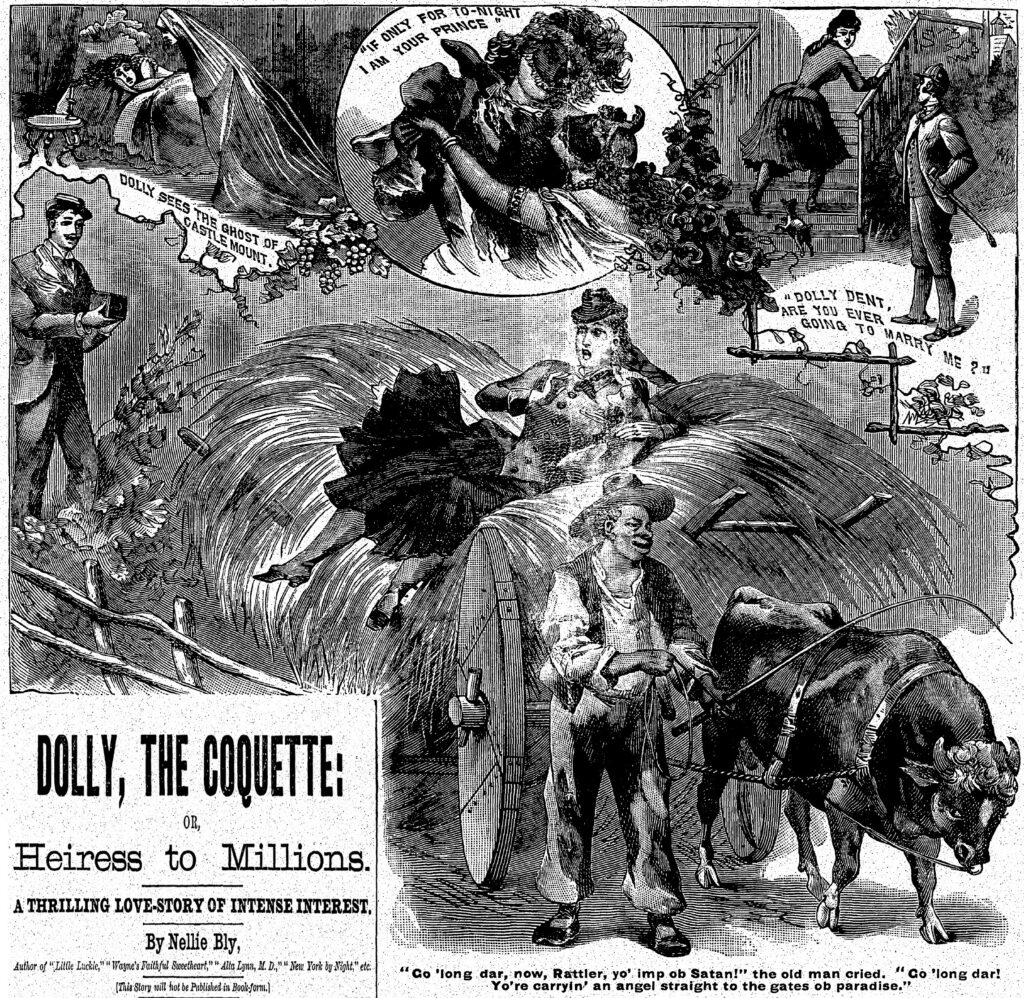

In the case of the minstrel show, it was ridicule. White performers donning blackface to sing and act out grotesquely exaggerated parodies of what they thought was Black culture for white audiences. The dialect alone is appalling (an example of which is used in the caption to the image above).

It is worth noting that Nellie Bly’s own pseudonym was appropriated from the titular character of Stephen Foster’s song “Nelly Bly,” which exhorts a Black serving woman to “bring da broom along” and “hab a little fun.”

It is also worth noting that Elizabeth Cochrane did not choose the name Nellie Bly for herself, that she was given it by an editor. Neither did she abandon it. Which is a good analogy for Bly when it comes to race. She was not more racist than her contemporaries. Neither was she less racist.

Some of Bly’s other novels deal in casual racism. Anti-Chinese feeling was very high in America in the 1890s, and Bly briefly uses an offensive Chinese dialect in two of her novels. There is questionable use of people of Spanish descent in The Love Of Three Girls, especially the “hot-tempers” of the men. Little Luckie deals with the evils of a “gypsy queen,” though without any real understanding of the Romani, using them interchangeably with “Bohemians.”

All of these are problematic. But none rise to the level of Sisley, the“mammy” character in Dolly.

As it happened, I was scanning through issues of Life magazine as I started editing Dolly, looking for theatre reviews by Bly’s then-beau, James Stetson Metcalfe. I was shocked at the prevalence of offensive cartoons that employed the exact written dialect for Black Americans as Bly does in her novel. Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle used this dialect for a villainous Black henchmen in his Sherlock Holmes story The Three Gables, complete with the n-word and references to his “woolly head.” It was clearly common. Which makes it no less offensive.

Early in the novel, Dolly commits murder, then allows Sisley to take the blame and be condemned to hang. Sisley, who speaks in that same dialect and freely uses the n-word when referring to other Black characters, loves her Miss Dolly so very much that she is willing to die rather than let harm befall her mistress. While eventually Dolly contrives to free Sisley, it is a gross example of innocent Black lives being disposable to save guilty white lives.

If all the characters were white, there would be nothing objectionable to the story. Hell, if it was a New York heiress with a French maid, it would be fine. The story itself is not about race. But by the use of race, it becomes incredibly problematic and offensive.

Reading the novel was hard for me. There is nothing in it that was not commonplace at the time more. If it had not been lost, it would simply be another unfortunate upholding of the prejudices common to the era.

But because it was lost, and because I was the one who found it, reintroducing it became my decision. If I put Dolly back into circulation, I would be actively upholding the prejudices of a past era in the modern day.

With each chapter I questioned my responsibility — to history, to the record, to society, to Nellie Bly’s legacy. I could not pretend she did not write a racist novel. I also knew I could not allow myself to profit from it. I considered donating the proceeds to a scholarship. By Chapter Six, I knew even that would not be enough.

It isn’t often one looks to corporate America for moral guidance, but in this Disney sets an example. Song Of The South, their 1946 film, is a near-exact parallel. In it white children are given aid by a loyal, cheerful, parental, formerly-enslaved Black American. While it lacks the plot of murder and cover-ups, it reinforces a harmful caricature of Black Americans in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. So Disney has put it in the vault. They do not pretend it doesn’t exist, but they also recognize that it is wrong to promote entertainment that upholds white supremacy.

I am not an historian. I’m a novelist with a background in both theatre and history. Though I happen to have made a significant historical discovery, I still view the world through an entertainer’s eyes. As such, I know full well that the art we consume matters. More importantly, the art we put into the world matters. This is an age of Lovecraft Country,Watchmen, and Black Panther. It’s time to break down the barriers, not reinforce them.

In the same year that we have our first Black woman as Vice President of the United States, when Stacy Abrams is rightly being lauded for her amazing work in Georgia, when Joy Reid is the first Black woman to anchor a primetime news show, to release a book that contains the backward tropes we are just now barely escaping would simply be irresponsible.

Black women are the unacknowledged leaders of progress in America. Perhaps this is because, suffering the twin scourges of racism and sexism, they have more understanding of what needs fixing in this nation. They see the promise of equality, and the barriers that remain. The Democratic Party would do well to listen to Black women.

To that end, I reached out for guidance to several Black women in my life — in itself problematic, as it is not the job of Black people to educate white people on questions of race. Racism comes from white supremacy, and it is white people’s problem to solve.

Prefacing my request for guidance with that very thought, I presented my dilemma. Some of these women are recent friends, some I’ve known nearly all my life. All agreed to weigh in. Naturally there were varied opinions, but it came down five-to-one against publishing. The argument for preserving the historical record was strong, but the argument against upholding white supremacy was stronger.

The universal agreement was that I could not change a word of Bly’s language. Either I published it as she wrote it, or not at all.

Which made my decision easy. I was not going to publish a novel — a piece of entertainment — written by a white woman that put the n-word in the mouth of a Black woman. Decision made. Done.

There are several justifications for publication ready at hand, and just as readily dismissed:

Would it not be wrong to cover up this piece of Bly’s history, pretending it didn’t exist? Absolutely. Hence this article, as well as my note in the Introduction to every volume of the Lost Novels I have released. I won’t pretend she didn’t write Dolly. In fact, she likely considered her portrayal of a loyal former-slave complimentary. It isn’t.

Bly was a product of her time, when minstrel shows were at the height of their popularity. It doesn’t mean that she was racist, does it? Close. It means she was no more racist than the society in which she lived, which is not the same as not being racist. And in a world where the goal is to be anti-racist, putting this repugnant trope out there as something fresh and new is simply intolerable.

It is wrong to judge historical figures by modern standards. I agree with this sentiment. People should be judged in the context of their own times. However, in matters of human rights, of equality, of dignity, we must look at our forebears and find them wanting. They knew right from wrong then, and if they chose to ignore it, well, they should be held responsible. There’s a meme that says something like, “Excusing someone’s bigotry as being ‘a product of their time’ erases all those who fought against that bigotry at the time.” Exactly. Worse, excusing them then leads the way to excusing us now. I did not tolerate racism in my grandparents, despite them growing up when Segregation was the law.

What about scholarship? Researchers and historians should have access to this novel. They do. They have the same access they have always had — more, since now they are aware of its existence. I cannot make it disappear. But neither do I have to work to make it readily accessible.

If you don’t publish it, someone else will. And that will be on them.

I do fret that making it harder to find will turn this novel into a fetish object for racists. I can only hope that the fact that Nellie Bly was a trailblazing feminist icon will diminish their zeal in unearthing what is, in truth, a pedestrian-level degree of racism for the era.

Because it is important to remember this, too: Bly was ever fighting injustice. She was eager to support the poor and the downtrodden, the swindled and the abused. She championed equality. She was ever interested in the plight of women.

Bly’s racism, therefore, is a product of her time. Her fault was not being able to transcend her era to see the grotesquery of that racism.

As the only living person who has read every word Bly penned for public consumption between 1887 and 1896, I am dead certain that if Bly were alive today she would be the first to disavow this novel. She would see it as I do, an unacceptable prolonging of outdated tropes that should have died with the Confederacy.

Bly is not here, however, to make that determination. In the final balance, it comes down to me. And I say no. I refuse to perpetuate the stereotypes employed in Dolly The Coquette. While I could publish and claim not to be a racist, I could not publish and remain anti-racist.

Onwards.