NEW YORK WORLD – Sunday, December 18, 1887

Nellie Bly in Short Gauze Skirts Kicks at a Mark

How it Feels to Go About in an Abbreviated Costume—Making Her Outfit—Holding on a Bar to Practise—Why It Is Healthful—Comments of the Old Professor—It Seems Easy, but Requires Much Hard Work.

I have been learning to be a ballet dancer. I have always had an almost manlike love for the ballet, and when I go to spectacular plays and to the opera I try to get close to the bald-headed row. Breathless with admiration I have watched the ballet twirl on its toes and spring into picturesque attitudes, the very poetry of motion.

It seemed so lovely that I longed to learn the art. Prof. Mamert Bibeyran, of No. 1 Irving Place, advertised for pupils, and I ascertained that for two years he had conducted the ballet of the American Opera Company and that the last success of the Casino ballet was the result of his instructions. I decided that he should teach me what I wanted to learn.

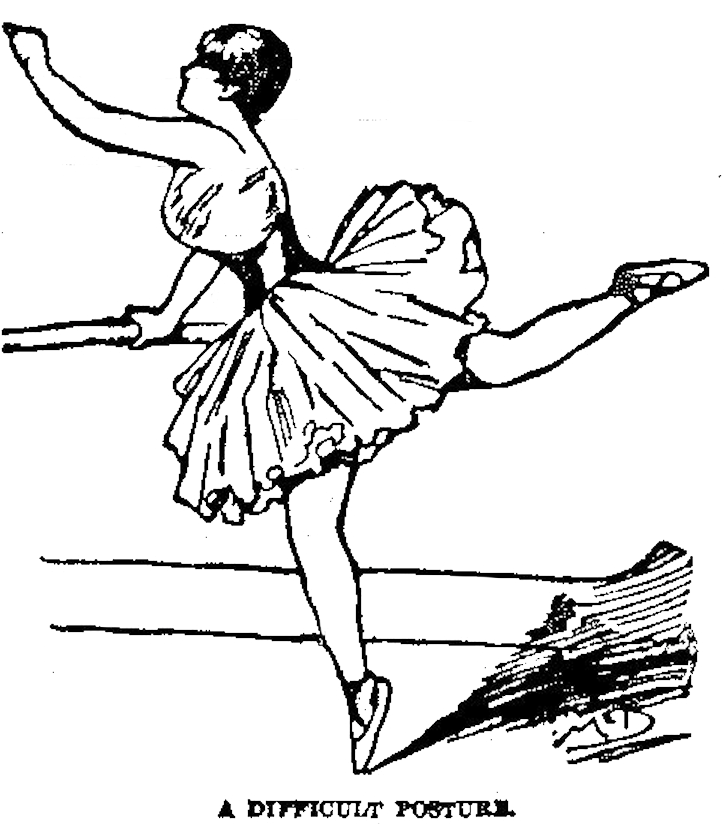

I felt quite brave until I entered the dance hall. Pausing at the entrance I saw at the further end of the hall a young girl in short gauze skirts. She was holding on a bar with one hand and her foot was swinging out into space to the time of a violin in the hands of her instructor. It looked very comical to see her foot go out first front, then to the side and then back, slowly and regularly, while the rest of her body was in perfect repose. She saw me and warned the professor of my presence.

“I want to learn ballet dancing,” I said, by way of introduction, when he came up to me. “How much do you charge?”

“Are you a professional?” he asked. “Do you want to learn for the stage?”

“Well, I am not on the stage at present,” I replied, evasively. “I want to learn ballet dancing, and if I like it I may go on the stage.”

“Yes,” he said, with an encouraging smile. “It is a great art, and requires time and patience to learn. My terms are $20 a month for a lesson of one hour daily.”

“Very well. I am anxious to begin. What sort of a costume must I get?”

“Come, this young lady will tell you,” and he led me to his pupil in short skirts. She was a pretty French girl, with no knowledge of English as it is spoken. She gave me her hand in greeting in a very pretty manner. Her eyes were sparkling, and her cheeks were pink from the exercise. She was well worth looking at.

“Anything will do to practise in,” she said. “I bought crinoline,” holding up the edge of her dainty little skirt. “It takes twelve yards for the skirt, and this only cost me seven cents a yard. Three yards of velvet or plush is plenty for your bodice, and then you must have ballet slippers made.”

“Anything will do to practise in,” she said. “I bought crinoline,” holding up the edge of her dainty little skirt. “It takes twelve yards for the skirt, and this only cost me seven cents a yard. Three yards of velvet or plush is plenty for your bodice, and then you must have ballet slippers made.”

After receiving a few more suggestions about my costume, I gave an assumed name and address, shook hands with my new acquaintances and started out on a buying expedition. I first went to a stage costumer, and as she wanted $10 for an outfit, I concluded to make my own. Accordingly I bought twelve yards of black crinoline and decided to make the bodice of an old evening dress do for the ballet. “How much will a pair of ballet slippers cost me?” I asked a man who makes only theatrical shoes.

“It all depends on the material,” he said. “I can make you a satin pair that will last you a long time if you care for them, for $1.59.” So he measured my foot and I went away feeling sorry ballet suits were no more popular, they are so cheap.

That evening I tried to imagine myself a lonely ballet girl such as I had read of in thrilling romances, sitting in her bare attic room, making her stage costume of gauze and spangles, while the tears coursed down her pallid cheeks. I sat on the floor while I divided my black crinoline into three equal parts. Then I cut them, lengthwise, three different sizes. The longest was a little shorter than an ultra fashionable bathing suit and the third and shortest was—well, it was pretty short.

At 3 o’clock the following day I was at the hall. The Professor showed me the dressing-room and I was left alone. That first dressing was funny! I put on the tights and my black crinoline skirts. I never realized until that moment how short they were and how extremely stiff. My ballet slippers were awaiting my arrival and they were the prettiest little one and a half satin slippers I ever saw. I grew so proud of them I began to feel glad my skirts were quite short enough to show them to advantage.

Dressed at last in a ballet costume I looked at myself and marvelled at the change. There is everything in dress after all. I had entered a quiet, staid-looking spinster, and presto! I now looked like a sixteen-year-old girl and quite flippant and pert. I did not feel as I looked, however. All at once I grew painfully modest. It is not so bad to wear a bathing-suit when everybody else around has one on, but when everybody is in full dress one would feel awfully short in a bathing costume. That was my position. I felt as if I had forgotten and gone to a full-dress reception in a bathing suit.

For an instant I was inclined to put on my street dress, and pleading sudden indisposition, take my leave, but I looked so healthy and there was no powder-puff around, so I was afraid the statement would not bear out. Several times I got up and started and my heart failed. I went back again and sat down. I pulled at my skirts, but they would not lengthen. I began to fear the Professor would soon think I had fainted or committed suicide. “It’s a go,” I said mentally, and I opened the door and closed it rather quickly behind me, lest I should grow faint-hearted and go back in. The Professor was sitting in the hall playing dreamily on the violin. When he heard the door close he looked up and said:

“Ah!”

That “ah” was meant kindly, but it reduced all my courage to pitiful shakes. I caught my crinoline skirts in and vainly tried to increase their length by bending. The Professor smiled.

“Oh, this is your first appearance in ballet skirts, I see. Never mind, you’ll get used to them in a little while,” he said kindly. I did. Before my lesson was finished I was sorry to exchange my short, airy costume for the heavy garments fashion says we must carry.

“And now we will begin,” said Prof. Bibeyran. “Catch hold of the bar with your right hand.” The bar is a long pole fastened firmly to the wall. It is for beginners to support themselves on until they learn to balance on one foot.

“Now, first position,” he said, taking hold of the bar and facing me. “You put heel to heel, with the toes in a perfectly straight line. When I say, ‘Bend,’ you raise the heels slightly, at the same time bending at the knees. When I say ‘Rise,’ you pose the heel which is touching them on the floor again, and straighten the knee. You do this movement eight times. Now begin.”

I clutched the bar tightly and put my heels together, my feet in a straight line north and south. “Bend,” said the Professor. I bent my knees slowly, going out in the direction of my feet. “Rise,” and I go to my first pose. “Bend,” continued the Professor. “There, do not bend with more weight on the right knee. Keep firm, and bend with your weight full in the centre. Rise.” I felt relieved to get back.

“Bend,” he called again. “Hold up your head. Never look at your feet; it is awkward. Keep a bold front, the back perfectly straight and stiff; the movement all at the knees, please, the weight on the centre. Now rise, bend, rise. All right; turn.”

“Bend,” he called again. “Hold up your head. Never look at your feet; it is awkward. Keep a bold front, the back perfectly straight and stiff; the movement all at the knees, please, the weight on the centre. Now rise, bend, rise. All right; turn.”

“Why turn?” I asked.

“Because one side must have the same ease and proficiency as the other. If you learn exercises on the piano with the right hand only you could not play equally well with the left. Just so with dancing. If you would not learn one side as well as the other, I feel you would be a one-sided dancer. Now, again, this time raise the arm that is not engaged with the bar.”

I put my right arm up with a sudden movement, very emphatic and according to my master, very ungraceful.

“Keep the little finger straight and the other three lightly closed. Rest the thumb on the index finger—so. It gives the hand a small appearance from the front. Never turn your hand flatly to your audience, but always give a side view. Now, raise the arm out from the body, curved and then slowly open it in a straight line with the shoulder. Keep the elbow turned back—it looks badly in front and will show the bones when there are any. Slender girls must always be more graceful than plump ones, because there is fear of showing ugly angles.”

At first it seemed a still, unnatural position, but I persevered.

“When you close,” he continued, “bring the arm gracefully down, with the elbow well out from the body. You want to always show the lines of the waist, and you can’t do it with the elbows tight to the ribs.”

My cheeks were burning and I felt as if I had taken a new lease on health and life by the time I had completed my first lesson. I have tried swimming, dancing, driving, riding, fencing, swinging clubs and the gymnasium, but none of them ever equalled the perfect and exhilarating exercise I got during my ten days learning to be a ballet dancer. I felt quite eager for my second lesson, and began to seriously contemplate exchanging literary work for the ballet. I kicked off my long skirts and donned my short ones with much pleasure.

“Do you only have professional people as pupils?” I asked of my ballet master.

“Oh, no,” he replied. “I teach deportment and society dancing as well. I have some pupils, society people, who are anxious to carry themselves well, and the best way to obtain it is to study deportment or the ballet. It is not only the key to all dances, but the key to grace and ease. I call this calisthenics instead of ballet dancing.”

“Well, they tell me that ballet dancing impairs the health,” I said.

“Ridiculous, my dear child. It gives force to the nerves and muscles and develops the body. It throws the head up, the shoulders and arms back and turns the feet out. This is the only exercise which develops all parts of the body. In Boston I have had doctors bring women whose health was impaired to me for care. Now, after our little lecture, we will go to work.”

“We will commence at first position, the same as you learned yesterday.”

I found my master was going to make me perfect in every exercise before he allowed me to pass it. This would use up all my lessons and I would have seen very little of what’s to learn, so I urged that he put me forward.

“This is an art, and if you do not learn the first well, you cannot learn the rest.”

“But I want to see what it is like. Rush me on and give me an impression of what it is.”

“My dear child, I am not all-powerful. I cannot pass my hands over your head and make you a ballet dancer. How can you take an attitude when you can’t balance on one foot, or how can you pirouette when you have not learned to stand on your toe?”

“Take first position.” I did, heel to heel. “Slide a point in line with your shoulder.” This was done by raising the heel and sliding the foot away from its mate, leaving a distance of fifteen inches between them. “Pose the heel.” I let my heel rest on the floor. “Now bend and rise without lifting the heels from the floor and then close front, ankle with ankle, which leaves you in third position.”

This was done repeatedly until my master was partially satisfied. Then he told me to stay in third position and bend and rise, lifting the heels. Ankle touched ankle, and I needed the aid of the bar to keep my balance. Fifth position was more awkward still. The feet had to be closed tightly, with heel touching toe, and so without moving I had to bend and rise. It was with difficulty I did it at first, but after a few days’ practice I was surprised at my own suppleness.

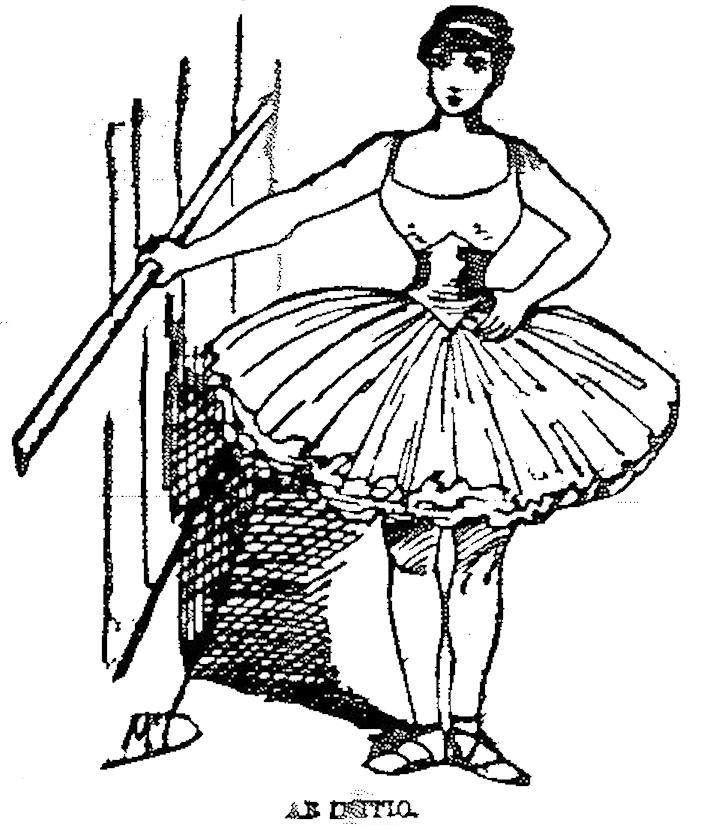

“Now make very straight point,” said my professor briskly.

“What is straight point?” I asked.

“It is to slide along the floor, curving the foot and keeping the toe on the floor, the knee very straight and stiff, allowing movement only to the hip and keeping the rest of the body as firm as a statue. Pose your arms nicely, now batements.”

“What does batements mean?” I asked helplessly, standing all the while with my toe posed on the floor.

“It means to do this,” and the professor gave a sudden kick way up in the air.

“Oh!” I said; “batements means to kick. All right, here goes.”

“No, no; not kick,” interposed the master quickly. “That is not elegant; mules kick. Now do this in good time—one, make a point; two, batements; three, down; four, close the front. Well, repeat.”

Did I kick? Well, it was the funniest exercise of the lot. I felt a little diffident at first and the kick was very low.

“Batement in line with the nose,” said the master. “Longer, longer.”

He put out his hand on a level with my chin, I kicked did not touch him. He urged me to kick higher. I did, and my foot touched his hand. He raised his hand to a level with my eyes and I launched a kick that surprised the gentle master and myself. You see, I was so eager to kick that I forgot all about my balance. Well, I did not fall, but I cut one of the most laughable capers one ever saw. Next I had to kick out at the side, always retaining an immovable front position. It was easier than the front kick. The back kick was the most difficult of all.

He put out his hand on a level with my chin, I kicked did not touch him. He urged me to kick higher. I did, and my foot touched his hand. He raised his hand to a level with my eyes and I launched a kick that surprised the gentle master and myself. You see, I was so eager to kick that I forgot all about my balance. Well, I did not fall, but I cut one of the most laughable capers one ever saw. Next I had to kick out at the side, always retaining an immovable front position. It was easier than the front kick. The back kick was the most difficult of all.

“The knee must be kept stiff during all the movements at the body. Strike out the foot as if you want to touch the crown of your head. Bravo.” I never knew before how much pleasure there was in a kick and I fear had I continued longer I should have become a chronic kicker.

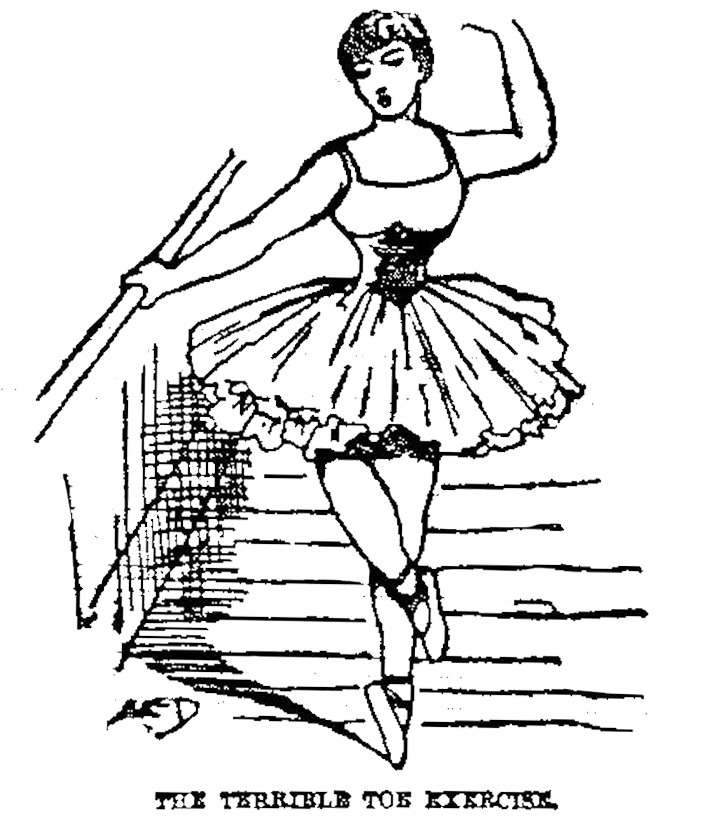

Soon after this I was given a most peculiar exercise. It began by slowly sliding the foot in a half circle to the front, to the side and to the back. The speed was increased until after awhile I was standing on one foot and the other was flying around in a circle like a top. Again I was told to slide a very large circle and let the toe but touch the floor in the rear.

“Raise your foot, curve the knee, bend the body at the waist and turn the face to the raised hand. That is attitude.” I did not bend exactly to please him, so he came, and taking hold of my shoulder and toe, tried to make them meet; at least it felt so to me. Afterward I could assume the position more easily. While yet in attitude he called:

“Straighten the knee and arm. Point the toe. Support the leg high. That is arabesque. Close.”

Again and again I repeated this, and not for a moment did I feel tired or lose interest. I must confess, though, that the following day I felt as if my bed had been too short. I was very stiff until I began to exercise and then it all left me.

In the next exercise I was told to stand on one foot and raise the other foot, resting the heel on the ankle. Then I had to make a kick with the knee straight. This was done higher and higher, each time with greater rapidity, to develop the muscles and make them firm but elastic. A few more exercises, which are too tedious to tell of, and I had, against my master’s advice, who wanted to make me perfect, finished “on the bar.”

I was now placed in the centre of the floor without any support, and to the music of the violin I had to move my arms in rotation, first with an outside and then with an inside curve. This was done with my feet in first position, then in second, and so on. If you want to know how difficult it is, place your feet lightly heel to toe and make curves above your head and at either side and in front. It is no child’s play. This rotation of the arms is made with the feet in all the different positions in order that one may be sure of her balance. Then all the exercises were gone over again, the only difference, which is all the difference in the world, being that I had no support, but must balance myself or fall. Attitude and arabesque are done. If everybody studied ballet dancing for a few lessons the fine work of the dancers on the stage would be more appreciated. It looks very easy from the front to see the graceful girls fall into those lovely positions, but it takes years of practice, and hard work at that, to be able to do so.

I was now placed in the centre of the floor without any support, and to the music of the violin I had to move my arms in rotation, first with an outside and then with an inside curve. This was done with my feet in first position, then in second, and so on. If you want to know how difficult it is, place your feet lightly heel to toe and make curves above your head and at either side and in front. It is no child’s play. This rotation of the arms is made with the feet in all the different positions in order that one may be sure of her balance. Then all the exercises were gone over again, the only difference, which is all the difference in the world, being that I had no support, but must balance myself or fall. Attitude and arabesque are done. If everybody studied ballet dancing for a few lessons the fine work of the dancers on the stage would be more appreciated. It looks very easy from the front to see the graceful girls fall into those lovely positions, but it takes years of practice, and hard work at that, to be able to do so.

I began the preparation for the pirouette by standing on the toe of one foot. The heel must not touch the floor. The pirouette, attitude and arabesque are the most difficult things I attempted. It would be folly for me to insinuate that I learned them. It takes years to become an artist of the ballet, and I could not do it in ten lessons. What I attempted was done imperfectly, and much against the wishes of Prof. Bibeyran, but my only desire was to get an insight into the work done by the ballet.

The first thing to strive for in ballet dancing is firmness and a good balance. Another exercise is to take one position, bend, jump with both feet off the floor, and close in a different position. While doing these exercises the master plays the violin, and the dancers count to keep time, changing rapidly from one position to another. But to attempt to tell all about the ballet dancing would take a volume. I know that is a grand exercise, and that while I was learning everyone remarked my healthier appearance.

Nellie Bly