Shakespeare’s Macbeth explores the darkest recesses of the human psyche, delving into themes of ambition, power, guilt, and the consequences of one’s actions. Macbeth’s arc culminates in the “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy in Act 5, Scene 5, a poignant reflection of the character’s descent into madness and despair.

At the outset of the play, Macbeth is depicted as a valiant and honorable warrior. However, as ambition consumes him, he descends into moral and psychological chaos. This descent culminates in the despairing soliloquy, where Macbeth grapples with the consequences of his ruthless pursuit of power. His world crumbling around him, his once-promising future as king has turned into a nightmare of guilt, paranoia, and isolation. Lady Macbeth has died “by self and violent hands,” his kingdom is under siege by forces loyal to Malcolm, and the feared Macduff is coming to exact revenge. Haunted by guilt, Macbeth is faced with the grim reality that his ambitions have led only to misery, isolation, and ruin.

The famous soliloquy is often taken as a complete piece unto itself, an existential lament recited by actors with a deep sorrowful intonation. That’s not wrong—the speech’s powerful language certainly works. Just watch Ian McKellan’s brilliant, simple version.

However, there is a staging choice that makes the scene far more powerful.

First, it is vital to note the following pieces of context:

1) The first communication between Macbeth and his Lady is a letter (“They met me in the day of success”) in which he tells her about the witches and their prophecy;

2) After the murder of Duncan, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth begin to drift apart. He kills the grooms without consulting her, and cuts her out of the murder of Banquo entirely. After the banquet scene, they never share the stage again.

3) During the sleepwalking scene (“Out, out, damn spot!”), the Gentlewoman tells the Doctor:

Gentlewoman

Since His Majesty went into the field, I have seen

her rise from her bed, throw her night-gown upon

her, unlock her closet, take forth paper, fold it,

write upon’t, read it, afterwards seal it, and again

return to bed; yet all this while in a most fast sleep.

4) When Seaton enters to tell Macbeth that his wife is dead, Mac’s response is “She should have died hereafter; There would have been a time for such a word.” Now, he could carry on into the speech from there. “There would have been time for such a word tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow…” But the verb “creeps” upends this construction.

The speech itself is divided into two distinct sections, the first having several multi-syllable words and soft consonants and vowel sounds, the second having mainly one-syllable words full of plosive sounds. Two parts—as though originating from two minds.

It was my wife, director Janice L Blixt, who honed in on Lady Macbeth frantically writing in her sleep. She also pointed out the change in style in the famous “Tomorrow” speech.

Her analysis makes a strong case for the playing of the first half of the “Tomorrow, and tomorrow” soliloquy is Lady Macbeth’s suicide note.

Imagine this: Seaton enters after the blood-curdling cry offstage. The king says, “Wherefore was that cry?” In reply, Seaton holds out a blood-stained bit of paper with mad scribblings of writing all over it. The seal on it tells us that it is the same letter that Macbeth sent in the first scene, but it has been written over and over, in corners and on edges, until it is covered with words. Seaton says, “The queen, my lord, is dead.”

Imagine this: Seaton enters after the blood-curdling cry offstage. The king says, “Wherefore was that cry?” In reply, Seaton holds out a blood-stained bit of paper with mad scribblings of writing all over it. The seal on it tells us that it is the same letter that Macbeth sent in the first scene, but it has been written over and over, in corners and on edges, until it is covered with words. Seaton says, “The queen, my lord, is dead.”

Macbeth takes the letter from Seaton and waves him off. Looking at the paper, he says, “She should have died hereafter; there would have been a time for such a word” – referring to the letter. Then, squinting, he begins to read the scrawled words written by a despairing, sleepwalking Lady Macbeth:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death.

Macbeth then crumples the paper, and gives his bitter, broken reply:

Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

This past summer, playing the roles again, we took the idea a step further. In Lady Macbeth’s first scene, Macbeth comes onstage to speak his letter to her telling of the witches. Then at the end, as Macbeth speaks the first “Tomorrow,” Lady Macbeth enters, one last ghost conjured by her written words, to speak her final communication to him, ending in “dusty death.” Thus we neatly mirrored their first and last communications, bringing closure to their shared story.

This staging choice helps Macbeth play the existential soliloquy as more personal, building upon the loss of Lady Macbeth. Hearing her voice through these words, he is faced with her despair. He realizes how far he’s fallen, how little is left to him. It also highlights his isolation. Already deserted by the “false thanes,” he no longer has Lady Macbeth at his side.

In this construction, it is Lady Macbeth who contemplates the inexorable passage of time. Her repetition of the word “tomorrow” underscores the relentless march of time, each “tomorrow” representing another day of suffering and despair. Life has become a series of empty moments, devoid of purpose or fulfillment. The “way to dusty death” suggests a path leading inevitably to decay and oblivion. So she ends her life.

“Out, out, brief candle,” becomes a reply to her, and also a plea for his own life to end. Life’s emptiness and transience reflects Macbeth’s own emotional emptiness and isolation. This intensifies his despair, pushing him further into madness. Anger creeps into his words, as Macbeth viscerally likens life to a senseless story, “tale told by an idiot,” filled with noise and chaos but devoid of any real substance or significance. His use of metaphors such as “a walking shadow” and “a poor player” highlights his belief that life is a mere illusion, a fleeting and transient experience. Through these metaphors, Macbeth expresses his nihilistic outlook, where life has lost all meaning and value.

While the speech offers a window into Macbeth’s tortured psyche, it also connects to the broader themes of the play. Shakespeare uses Macbeth’s downfall to explore the corrupting influence of unchecked ambition and the destructive consequences of political ambition run amok. Macbeth’s obsession with power leads to the ruin of his own life and the kingdom of Scotland.

This is all made more powerful by having Lady Macbeth, who began the play by invoking the “spirits that tend on mortal thought” to fill her with cruelty, lamenting where this has taken them. She thought there would be no consequence to their souls. Ironically, it is Macbeth, through his “If it were done” soliloquy, who rightly foretells their fate. He saw it coming, and yet could not stop.

There are actors who rebel at this when it is suggested. After all, this is the most famous speech in the play, and they are determined to play it. Which is perfectly fair. But Janice and I argue that the storytelling is heightened and improved for the audience by giving Macbeth and Lady Macbeth one final time to share the stage and lament what has become of their vaulting ambitions.

The “Tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy is more powerful, and Tragic, if shared.

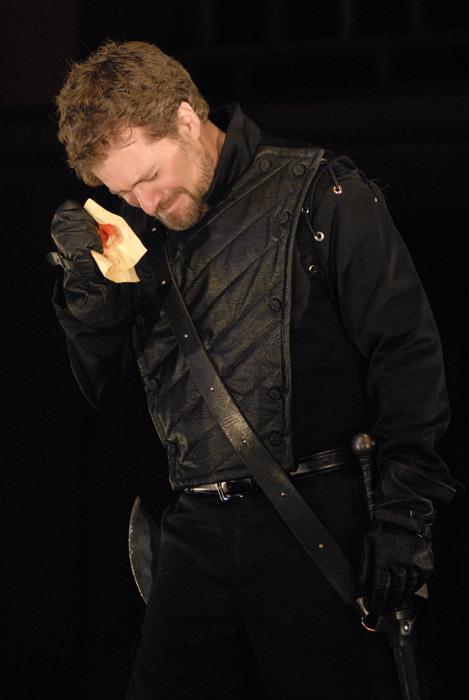

Rehearsal photo, Macbeth, 2023, Michigan Shakespeare Festival

Note: As I’m sure readers have noticed, it is a dire time for live theatre. If you appreciate this content, and the ideas we explore through performance, please consider supporting the Michigan Shakespeare Festival by buying tickets, donating, or joining our Patreon page.

The first time I saw the scene, it was powerful. The second time, after Jan talked about it in the BardTalk, it was even more powerful. Your writing adds more depth. You two show that it doesn’t matter how many times you see a play, or perform a role, there is always has more to discover in Shakespeare. Thank you.