I recently watched The Punisher series on Netflix. I was hesitant going in. Not because I thought it would be bad, quite the opposite. John Bernthal is terrific, absolutely compelling to watch. The whole production team did a spectacular job. And they almost – almost – addressed my deepest qualms. They came so close to telling a perfect story. But in the end they made the mistake everyone does with the Punisher.

They make him heroic.

That’s a problem, because the Punisher is not a hero. In fact, he started as a villain.

Now, sometimes you want to root for the villain. Shakespeare’s Richard III is absolutely a villain, and he works hard to get the audience on his side. Part of the allure of Hannibal Lector is to see him get away with his monstrosity. Walter White’s descent into villainy takes us along his slippery slope, and we absolutely want Dexter to off the next bad person on his hit list.

But in every one of those cases, we are careful to keep our distance from the lead. We know we’re not supposed to be like them. We’re not meant to empathize with them. It’s a dark mirror, and we walk away thinking ‘That was fun, but thank God that’s not me’. While they’re enjoyable to watch, I don’t know anyone who fantasizes about being any of those characters. Because the creators were smart enough to know that, however often they might make us empathize with the villain, he's still a villain.

That’s not true of the Punisher. Somewhere along the way, he became a hero.

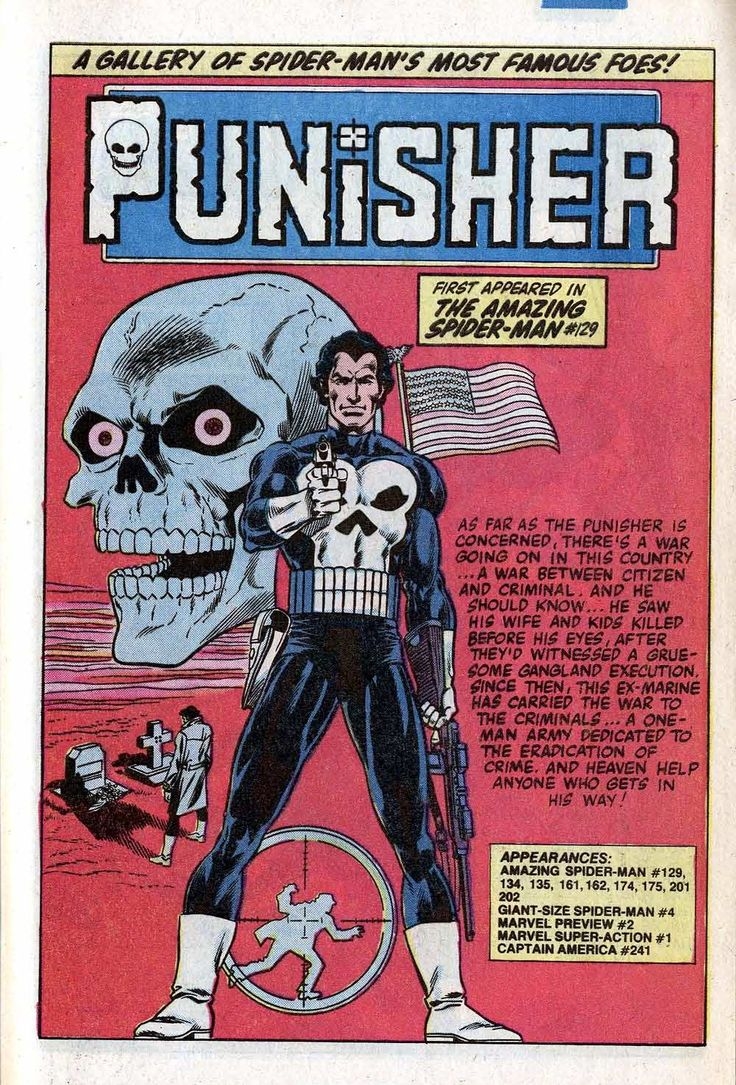

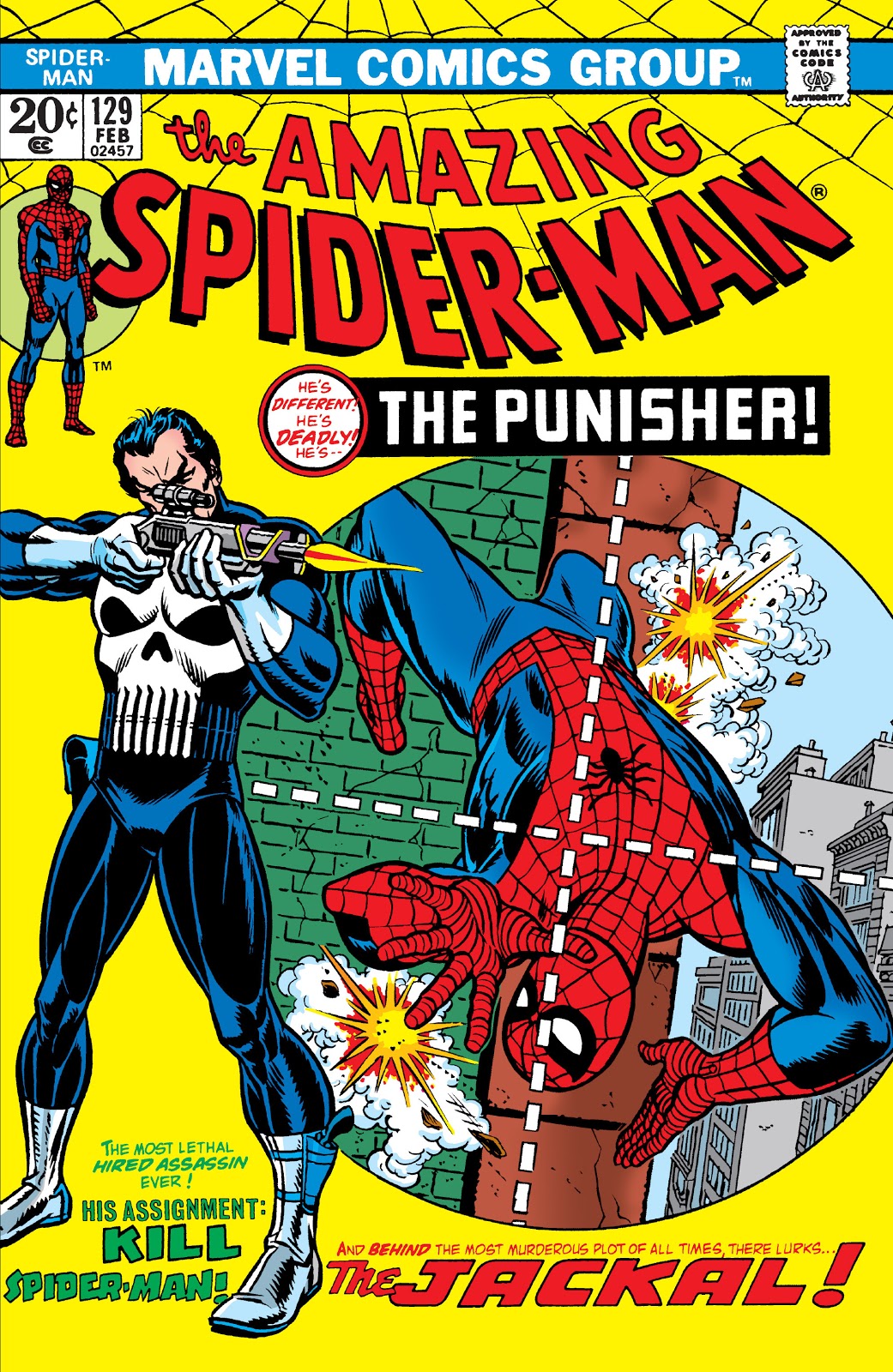

That’s not how he started, of course. He began as a villain. I have the Spider-Man comic in which he first appears, duped by another villain called The Jackal to make Spidey his next target. Here, the Frank Castle is basically a hitman who murders criminals. Yes, he’s got a tragic backstory. But at no point in that story do we mistake him for a hero. He’s a murderer. It’s just that he murders other murderers.

That’s not how he started, of course. He began as a villain. I have the Spider-Man comic in which he first appears, duped by another villain called The Jackal to make Spidey his next target. Here, the Frank Castle is basically a hitman who murders criminals. Yes, he’s got a tragic backstory. But at no point in that story do we mistake him for a hero. He’s a murderer. It’s just that he murders other murderers.

And that’s where things get dicey. This was the 1970s, the heyday of Revenge movies. Of the ‘antihero’.

By definition, an antihero is a protagonist who has none of the qualities of a hero, such as idealism, courage, or morality. Tony Soprano, Walter White, the Man With No Name. All defined by their moral ambiguity.

Antiheroes are great. Edgy. Very James Dean. I enjoy a good antihero as much as the next person. I love Rorschach in Watchmen.

But here’s the rub – when all our heroes are antiheroes, what does that say about us?

The Punisher proved popular enough to warrant another appearance. Then another, and another, then guest appearances in other comics. Somewhere along the line, he became the lead, with his own comic. Then a second series. Then a third. Then three movies.

The villain had become the hero – not even an antihero, but a straight-up Marvel hero, often equated with Wolverine and Ghost Rider. Only trouble with that is, Frank didn’t change – or if he did, it was only cosmetic, becoming more ruggedly handsome. But his methods didn’t change, nor did his goals. No, the Punisher didn’t change. Only our acceptance of him did.

Now, some Punisher comics are really good. Some are violence porn. Some are not just awful, but misguided (the time he began shooting at jaywalkers and litterers, or his time in blackface). All of them were guilty of that thing I hate most in modern action stories. I call it A-Teaming – a gazillion machine guns firing, all of them missing. No stray bullets killing civilians, the hero only ever getting a pretty flesh wound. Otherwise he’s able to dodge and outrun a hail of bullets. That’s a very dangerous myth, one that we continue to spread in all our action stories. Sorry, kids, you can’t outrun a bullet.

I was profoundly glad when his various series just seemed to peter out. Interest had waned. I had hoped we, as a culture, had gotten Frank Castle out of our system.

Then came the Marvel Netflix series Daredevil, which uses violence excellently well (see: the hallway fight, the stairwell fight). Violence with cost, for a purpose. The second season promised to introduce the Punisher, and I was…

Excited. I mean it. I was genuinely excited.

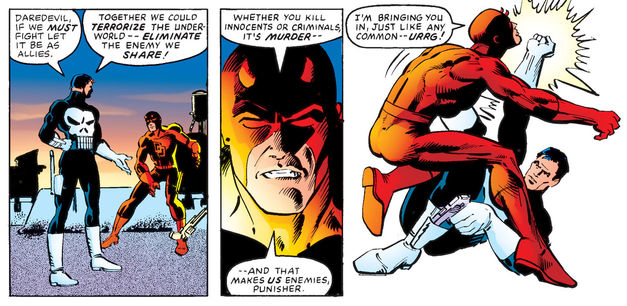

You see, the best use of the Punisher ever was in the pages of Daredevil. There they had the conversation about the nature of vigilantism, of methods and motives, of goals and results. Written by Frank Miller (before his crazy fascist days), one particular debate between Daredevil and the Punisher was profound. Frank Castle served as Matt Murdock’s dark mirror. He was not a hero, but a foil to our hero, which made him so much more compelling. There was no mistaking him as a role model. Instead, he challenged our role model to question himself. Therein lies great storytelling.

That’s the thing about antiheroes. We only recognize them in the face of actual heroism.

That’s the thing about antiheroes. We only recognize them in the face of actual heroism.

Imagine my joy when that exact debate ended up on the screen. After countless many iterations in comics and in film, someone had finally figured out the perfect way to use the Punisher. I was not only quite impressed. I was relieved.

Then I heard they were giving him his own series, and felt sick. It had happened again. We had mistaken the foil for the hero. We had looked at the complex villain/antihero and decided, because he only murdered murderers, that we could make him a hero.

I usually binge the Marvel shows. Not Iron Fist, of course – couldn’t make it beyond the first episode of that one. But all the rest, I’ll binge them the day they drop. (First season Jessica Jones is the best, followed by both Daredevils. Luke Cage is terrific for the first half of the series, then completely loses the thread, which is a crime).

When Punisher dropped, I didn’t want to watch it. I was afraid of pure gun fetishing. We’re living in a time of mass-shootings. Two people I cared about died from gun violence. For all that I work with violence in my art every day, I had no interest in sexy gun imagery.

I should have known better. They folks at Marvel/Netflix did a terrific job. When there’s violence in the series, it hurts. It has real consequences. Sure, Frank should have died at least five times over the course of the thirteen episodes. But this is a Marvel show, we can suspend a little disbelief.

Then we got to the end, and they almost did it. Frank has achieved his mission. He has punished all the people responsible for the murder of his wife and children. Two are still alive, but Frank has arranged for them to be taken down. He’s near death, and the ghostly spirit of his wife appears to him, reaching for him…

And he rejects her. Because revenge was now more important to him than peace.

How I wish the series had ended there. I mean, sure, I loved seeing the origin of Jigsaw (not the Saw killer, the comic book villain). But the last thing I needed was another gun fight. I didn’t want another set of civilians in peril. I especially didn’t want the government to make the insane decision to let him go free, because reasons.

No, I wanted the series to end on that most powerful moment. He’s been dreaming of his wife through the whole series. But when the time comes to join her, he is too in love with violence to embrace her. It’s not the power of life demanding he stay alive. It’s the power of killing that makes him refuse to die. He has nothing to live for but revenge. Yet that’s all he now wants.

Revenge has ruined him. Punished him.

They almost got that point across. He was almost perfectly tragic. Man, what an arc! But then they had to go and make him the hero one last time. Because the Punisher is a character forever teetering on the edge of the hero/villain divide, creators invariably make the error of giving him a heroic end, instead of a tragic one.

That’s the Tragedy of the Punisher. We keep trying to make Frank into a hero, when he’s always the first to tell you he’s not.