This article was the inspiration for Nellie Bly’s novel ALTA LYNN, M.D., on sale now from Sordelet Ink!

The New York World, Sunday, April 14, 1889

Nellie Bly Watches Their Anatomical Work in a Medical College.

An infirmary built up by the efforts of two brave women—An institution where girls may study medicine with hospital practice—Ambitious young women dissecting subjects with perfect indifference.

Phew! But it was horrible. I mean that it was horrible to see pretty, bright-eyed, rosy-cheeked young women busily engaged in dissecting. I saw some of these young medical students at work the other day picking, picking, picking, and so learning the beginning, the end and the object of the veins, arteries, nerves and muscles, and I haven’t had much liking for my dinner since.

It came about this way. I had been told that a dissecting-room was connected with the Woman’s Medical College, at 128 Second avenue. This naturally gave me a desire to see the creatures, whom men claim faint at the sight of a mouse, engaged in dissecting. Of course I thought it over for some time, and I wondered if the students ever fainted at the sight of the work before them. More than all I wondered if I could view them at their work unmoved.

Aside from the dissecting-room, the Woman’s Medical College and the Hospital—the New York Infirmary—with which it is connected, are very interesting. Their history contains the story of the lifework of two great women, who were the first, I am told, to do anything for the advancement of women in medicine. Away back in 1850, or about that time, Miss Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister, Miss Emily Blackwell, decided to study medicine and become practising physicians. The rebuffs and the trials they underwent before their object was accomplished would take a volume to tell. Miss Elizabeth was graduated at the Geneva College, which has ceased to exist. Miss Emily attended the Cleveland Medical College in Ohio.

These two young women then returned to New York City. They found that there was no hospital or dispensary in the United States open to women students, nor did persuasions or financial offers serve to open a way for them. In 1853 Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell applied for a position as attending physician in the Women’s Department of one of the city’s dispensaries. Her application was instantly refused, and she was told if women wished to do medical work among the poor they must establish separate institutions for that purpose. Prejudice against women physicians was so violent that in no place could they secure an opening.

But they were not discouraged. They engaged a building in Bleeker street and went to work to establish a hospital that should be open to women students. As a result of this noble purpose the New York Infirmary for Women and Children was incorporated in 1854. College charters, then as now, required a course of lectures and reading, and nothing more. Therefore, young women graduates were glad to live at the infirmary and to obtain practical experience there. These early students are now scattered over the country, successful and well-known women physicians, and have done great good in founding in different cities hospitals which are under the care of resident women doctors. In 1877 the Drs. Blackwell bought the building No. 128 Second avenue, and the Infirmary was removed there. A college was then opened in connection with the Infirmary. The College of Physicians and Surgeons would do nothing to aid the higher education of women in medicine. The Drs. Blackwell laid the case before the Faculty and made a proposition to establish scholarships—endowed to the amount of $2,000 a year—for women in their college, the students to be selected with care, entered as beneficiaries of the Infirmary, and to be withdrawn if they proved unworthy. This proposition was rejected, so it was decided to found a medical college in connection with the Infirmary.

A Hard Struggle At First.

An attempt was made to raise an educational fund of $100,000. They managed by hard work to raise $30,000. With this they bought the building No. 5 Livingston place, which is now the Infirmary, and the old building on Second avenue was given up to the College and Dispensary.

The building in which the Hospital is located is a most delightful place, roomy, bright and airy, facing on Stuyvesant Park, and has in the rear a large yard and open space. The stairways are broad and the rooms large. At the read is a veranda where patients may enjoy a sun bath. The Hospital is not self-sustaining, as the great majority of its beneficiaries are charity patients

“How did the Infirmary ever live at first?” I asked Dr. Emily Blackwell.

“By begging,” she responded heartily, with a smile.

At present there are some sixty patients in the Hospital. Those unable to pay are received free, but there are some who pay $5 a week as long as they stay, and $5 for an operation if one is performed. Private patients are charged $12 a week. The assistant resident physician, Dr. E.A. Walser, is a handsome young woman with a clear complexion, bright eye, and a fine command of English. She kindly showed me through the Hospital, and explained all that was interesting about it. The wards were very clean, and the patients look more than satisfied.

The most interesting ward is the nursery. I think there were some twelve or fifteen babies in all stages of flannels and humors. A nurse was bathing one little red-faced thing. The doctor led me by her to a crib where lay another red-faced atom and a bunch of cotton. Opening the cotton she told me to look. I did so and a shiver danced down my spinal cord. In the cotton was the smallest little red baby I ever saw.

“Come now, you must see the policeman,” said Dr. Walser, and I followed her forth, laughing at the kindly faced nurse who cuddled up the baby at my look of—well, not quite appreciation, and murmured:

“Oh! the dear little things, I love them.”

In The Nursery.

The policeman! Well, the doctor lifted him out of the crib and held him up for me to admire.

“We call him the policeman,” she explained with a proud smile, “because he is such a fine, big baby. Isn’t he, now? He weighed twelve pounds when he was born.”

His mother, who sat beside the crib, never smiled. She looked unhappy, as if life had never given her anything to be happy about.

A training school for nurses is run in connection with the Infirmary. At present there are ten nurses. They serve sixteen months before they are given a diploma. One month they serve on probation, then for the first six months they are paid $5 a month, and their boarding and washing furnished them free. They pay for the material—striped gingham—for their uniforms, but the making is furnished gratis by the Hospital. After the first six months they receive $8 a month. The nurses now live in a flat in Twelfth street.

No. 1 Livingston place and the adjoining house on East Fifteenth street have been bought and will be added to the Infirmary. They are to be remodelled this Summer and ready for occupancy by the Fall. The College then will be removed from Second avenue to Livingston place. There are about fifty students attending the College. It costs them $300 for the course of three years, with $75 extra for books, instruments and other necessary things. The course is much more thorough than that given young men students. If a young man buys lecture tickets and reads up enough to go through a simple written examination, he can become a physician without ever having attended a patient or having seen one attended. Medical colleges are money-making institutions, no record of scholarship is kept, and it depends largely on the student himself how often he attends.

It is entirely different with the young women. One of the features of the examination is in seeing a strange patient, making an examination and telling what the complaints and what the treatment should be. A free dispensary for women and children is connected with the College, and the young students have the benefit of practical knowledge. Students come from many countries to attend this College. There have been young women from China, one from India, two from Russia and several from Canada. One student from India was invited to Hyderabad by the native King and given a position as physician to his harem and to the city poor at a salary of $4,000 a year. Six languages were spoken in her dispensary. In four years she made herself financially independent, and then she married a Methodist minister and has discontinued practice. She now spends her time translating English books into the language of the people about her. Many other of the students’ histories are just as interesting, and they have accomplished great things in their way. I think the average of marriage among them is about half. Several of them are now the sole support of their families.

The Dissecting-Room.

The dissecting-room is on the top floor of the College. I followed the demonstrator—a man—up the winding stairs, and when the door closed behind me I had to put on my mental brace to prevent my imagination from making me faint. As the demonstrator said, the room is well arranged for air and light. There is a suit of four rooms, instead of one, where the dissecting is done, but as they are only partitioned off it seems like a single apartment.

I did not look at anything about me at first as I followed the demonstrator to the room where he was working. I had a confused glimpse only of bright faces, tables and discolored linen. I was afraid to see more. He closed the door between us and the students, perhaps to allow me to become more courageous. There was a subject on his table and I tried not to see it and to listen attentively to what he was saying. This, in my own language, as I am not able to reproduce his technical expressions, is the substance of what he was explaining:

“We get all our subjects from the Morgue. This,” indicating the object on the table which I could not look at, “is rather a bad one, as we have had it for quite a long time.”

“What is it?” I asked faintly.

“The body of a colored woman. We pay $5 for each subject that we get at the Morgue. They are brought here in wicker baskets. After dissecting we are expected to send all that we do not use back to the Morgue. I do not know how they dispose of it—bury it, I suppose.”

“What is the first thing you do to a subject when you get it here?” I asked.

“We inject into it arsenite of soda and then, twenty-four hours later, we again inject plaster of Paris colored by red lead to make the veins and arteries distinct and easy to find. The plaster of Paris must be sifted very particularly, for if the slightest foreign substance remains in it it clogs up and prevents the arteries from filling. You can see here,” taking his forceps and catching hold of a thread-like artery which looked as though it were filled with brick-dust, “what the plaster of Paris does. Now this,” lifting a white, limp thread, “has not received the plaster of Paris. Something has clogged it up. You see how difficult it would be to find the arteries in this condition, and hence the necessity for the plaster of Paris.”

Preparing The Subjects.

“Then what next is done?”

“We cut off the hair. We never sell it,” he said, with a smile, “nor make any use whatever of it. It goes in the barrel with what is returned to the Morgue.”

“Do the young women ever faint?”

“No. They are so interested in their study that they forget the unpleasant part of it. Of course when a body is first received it is harder to work with it than after it is separated into different parts. Then it really becomes no more to one than if it were a dog or anything else.”

I learned this to be true. As I went among the different tables I forgot that the rapidly baring bones had ever had life.

“Each subject costs us about $10,” said the demonstrator, as we went towards another room. “We charge the pupils $5 a part, and each student must dissect a whole body.”

In the second room were two young women of prepossessing appearance picking at a pair of legs. Although I know that this study is necessary to a medical education, I could not help mentally comparing the students to a pair of vultures. I used to watch the much-petted vultures of Mexico hanging over a dying animal whose eyes grew almost human as it found itself growing weaker and weaker and unable to get away from those funeral-plumaged death-watchers. And then it dies, with a look in its eyes similar to that in the eyes of a murdered man who had gazed upon his murderers, and with one movement those horrid black vultures, with the breath of pestilence, swoop down upon the body and pick its bones clean. Of great benefit to the country, yes, but a most revolting sight. So with the students.

“Do you want that door shut?” the demonstrator asked the busy students.

“We don’t, but the others do,” the one replied, with a smile. Their subject was a fat one, they explained to me, and as the two students had an objection to carbolic acid the other students protest against having them and their subject in the same room. They rested their elbows on their subject while they conversed with the demonstrator. He asked them questions concerning the different things which he pointed out, and they answered very readily, and correctly, he told me.

“It’s very hard to work with this subject,” said one of the young women, “because of the fat.”

“What is it?” asked the demonstrator, as he touched the horrid leg, which now knew no skin.

“A male subject,” she replied unconcernedly. “He was very large and fat.”

A Necessary Branch Of The Work.

We went out to another room where two young women were engaged on the other half of the fat man’s body. One had cleared the hand of most of its flesh and it lay there, bones and sinews. The demonstrator questioned her, and after showing me the large artery at the wrist wanted me to feel in the elbow while he worked the arm. I refused very decidedly. The other student had dug all the flesh away from the arteries in the neck and the doctor touched the “Adam’s apple” in the throat and explained to me that that was what the doctors wanted to cut open in Emperor William’s throat to remove the growth and get at the trouble on the inside. I looked at the head, which was cut in half; at the flattened nose, stuffed with cotton, and the poor mouth, sewed tightly shut, and I wondered.

“Was he black or white?” I asked the doctor, as I looked at the fast blackening skin.

“White,” he replied, but he knew nothing of his history. “We never do,” he explained. “I have had a great deal of practise in the hospitals and I have often wondered if I would not get some one I knew for a subject, but I have never recognized any one yet. We often have bodies who come from the hospital with the tag bearing their name and ward still fastened to their wrist.”

The girl students were so interested in their dissecting that they never lifted their head unless spoken to. They all wore gingham gowns to prevent their clothing from getting soiled, and had their heads tied up with cotton cloths, to prevent the odor penetrating into their hair, for it is almost impossible to get the odor out of hair or fur. Two of the students who suffer from weak throats wore wedge-shaped cardboard filled with cotton over their mouths and nose.

Of course dissecting must be done, and it’s nothing when one gets used to it, but I must say that I did not like to see the girls at it. I can well imagine, though, how interesting it would be after one got well started, and how little different parts would impress them as having been once what they are now—a living, breathing creature. The subjects are mostly old people and colored people. Children are very seldom dissected, though they can be had if desired. Sometimes handsome young girls are sent to the dissecting table, but such cases are rare.>

“We have had women artists come here for the purpose of study,” the doctor said, “but we rarely have visitors of any other kind.”

Of the founders of this useful work, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell has retired from practice and is now living in England. Dr. Emily Blackwell, a handsome woman with silvery hair, is still practising medicine in this city, and has the welfare of the Infirmary as much at heart as when it was started years ago.

Nellie Bly.

This and many more Nellie Bly articles can be found in NELLIE BLY’S WORLD, Vols 1 & 2, on sale now!

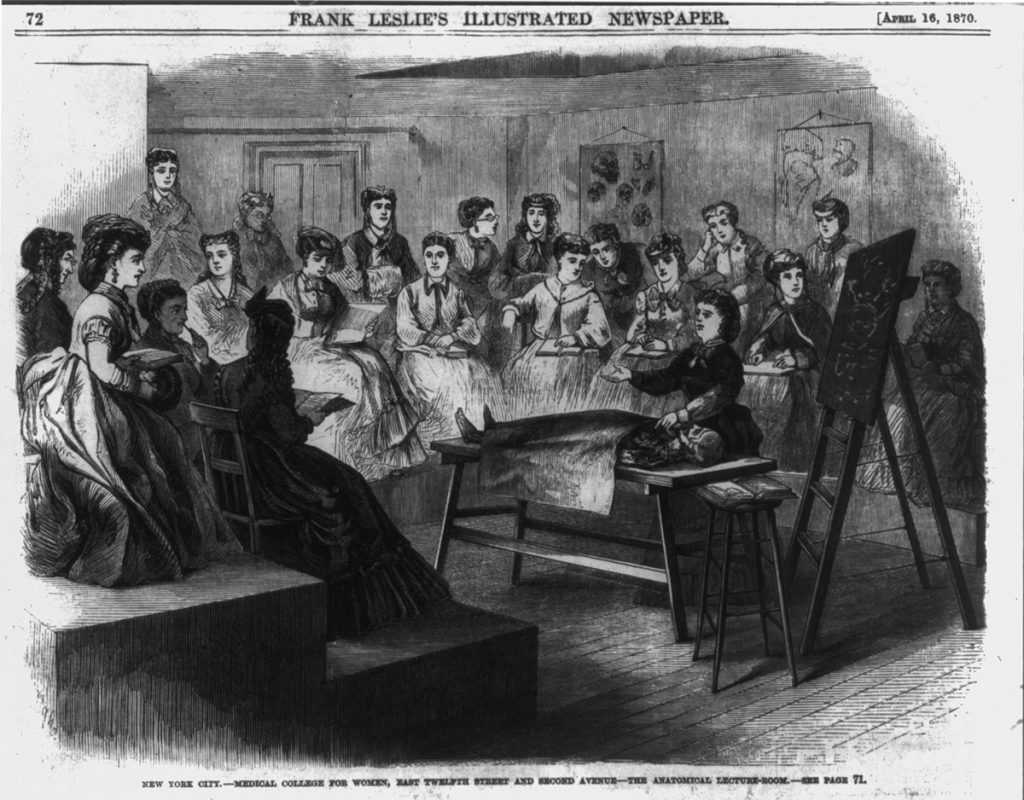

This image is from another story on women medical students, and portrays Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell giving a lecture.