THE NEW YORK WORLD – Sunday, December 23, 1888

The Sad Procession of Invalids Begging For the Simplest Food.

Nellie Bly Visits the Wretched Homes of Some of the Sufferers.

A Charity that Dispenses Nourishment to the Afflicted Poor with Liberal Hand and Irrespective of Race, Religion or Character—The Matron Tells of Her Long Experience—Mrs. Nugent’s Wretched Garret in Mulberry Street—A Hopeless Invalid, Blind and Penniless—The Quarrel Over Mrs. Healy’s Bank Account—Mrs. Siffert’s Misery and Suffering.

It was so near Christmas time—so near the one day in the year when almost the whole world rejoices and is happy, that my thoughts turned to those sad homes where misery, poverty and sickness give little chance for joy. I made up my mind to search out some of these afflicted households, and I turned for a few days from the gay stores and happy shoppers to the narrow streets where poverty and want was sadly apparent at every step.

But it is no simple matter to find the really worthy poor. I have had some experience among the very poor and I know whereof I speak. It occurred to me that I could find no better starting-point than the New York Diet Kitchen, at 137 Centre street, and I went there. I sat down beside the heater in the small, but very clean, oil-cloth floored room, and waited until the matron had given out an allowance to a patient. A little counter, covered with white oil-cloth, separated her from those who entered. A small desk in the rear of the room and several chairs completed the furnishings.

“If you do not object,” I said to the matron as she turned to me, “I would like to sit here for awhile and watch the people who come in for food. I would like to write something about the Diet Kitchens for The World.”

“I will assist you all I can,” she replied with a pleasant smile. “For I think the Diet Kitchen Association is the greatest charity in existence. We only help the sick, so we are not likely to do a wrong by keeping up indolent, unworthy persons.”

“Do you ever have any frauds?” I asked.

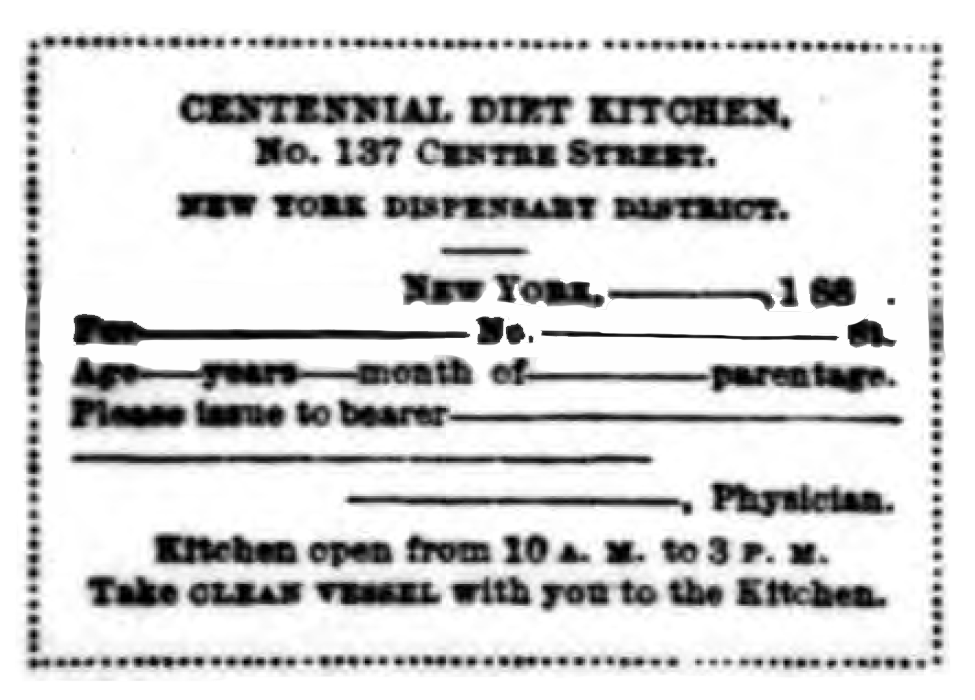

“No,” she said, again smiling, as she sat down. “That is one of the good results of keeping one matron for a long time. I have been here eight years, and I do believe I know everybody in our neighborhood, so I could not be deceived by unworthy ones. But then we do not forsake the sinner when he becomes ill. We help the sick without a question as to creed, race, color or character. Our patients, or customers, are treated at the dispensaries, and any dispensary doctor, knowing that a patient is in need of food or nourishment, can send them to us with one of these blanks filled out:

“You see on the last line they write what to give the patient and how long to continue the supply. We give them milk mostly. The doctors do not favor beef tea any more. They claim that there is more nourishment in milk. Two quarts of milk is an allowance. We also give boiled rice, mutton broth and such things. I use from fifty to one hundred quarts of milk every day.”

“How are the Diet Kitchens kept up?”

“By charity. We receive donations of every kind, and we are very glad to get them, especially old clothing and rags.”

THE THRONG OF CHARITY PATIENTS.

The door opened, and with a wave of cold air in came a thinly-clad woman, whose hair was the only warm thing about her.

“Good morning, Mary,” the matron said, rising from her chair. “How is your baby to-day?”

“He’s no better,” Mary replied, taking a tin pail from beneath her shawl and setting it on the counter. “Can ye give me a double allowance this mornin’? I can’t leave ‘im very well every mornin’ to come for the milk.”

“Have you enough medicine for him?” the matron asked, as she lifted the measure filled with creamy milk.

“I have about two teaspoonfuls left yet from that you bought ‘im,” Mary said, while trying to get the tin lid to fit the pail.

“I will give you some money to buy more to-morrow,” said the matron, and the woman left with her filled pail under her shawl, hardly thanking the matron for her kindness.

A little old woman, her shoulders all humped over from age and hard work, with a red nubia over her whitened head and a large gray shawl pinned about her, came in as Mary went out.

“Good mornin’, Mrs. O’Donnell,” she said to the matron, in a voice which sounded like a bagpipe on the next block.

“Good morning, Ann,” Mrs. O’Donnell responded cheerily. “How are you to-day?”

“Oh, God knows I’m no better, Mrs. O’Donnell,” she cried in a chant, without inflection of any sort. She had only one eye, and that she now turned upon me, letting a large splint basket which she carried slide to the floor.

“Is your daughter well, Ann?” asked the matron.

“Yes, please God, ‘un still workin’,” replied Ann, sitting down by the heater and rubbing her hands.

Mrs. O’Donnell asked me if I would not like to see her kitchen, and then telling Ann to “keep shop” until she returned we went down a flight of stairs to the basement. The kitchen was very bright and very clean.

“Do you do all the cooking?” I asked.

“Yes;” she replied, glancing with pride at the row of shining pans. “I come here at 7 o’clock and cook everything ready for the patients, who are served from 10 to 3. Occasionally I get a woman to help me clean up. The position is not an easy one. It shatters the nerves to be face to face with misery for five and six hours all day. After my hours are over here I visit all new patients in order to see that all is right and what they may possibly need. Still I love the work, and think this is the greatest charity association in existence.”

We went upstairs again, and a woman very fat and rather untidy, to say the least, was waiting for her allowance, which was promptly given to her.

LIFE-LONG DEVOTION.

“This is one of the noblest women I ever saw,” said the matron, nudging me hurriedly as the door was pushed open by a tall, plainly clad woman. Turning to her the matron said:

“Good morning, Miss Maxwell. How is your brother this morning?”

“He is no better, thank you, Mrs. O’Donnell. I think his end is near,” and she tried to smile though the lips quivered and the tears were near the eyes. She was unlike any of the others. Her pale, sad face had an expression of resignation. Her poor little bonnet and gown and shawl were plain, but spotlessly clean.

“What is wrong with your brother?” I asked her.

“It was rheumatism at first, but it is a complication of diseases now. The only work I can do is the fine finishing to vests. I cannot leave my brother alone so I take my work home.”

“She only gets three cents a vest for finishing work,” said Mrs. O’Donnell indignantly.

“Yes,” Miss Maxwell said, with one of her slow, sad smiles, “I worked yesterday, last night and to-day, and up to this time have just finished 21 cents worth. I cannot leave my brother and I cannot get anything else to take home. He was at the hospital once, but they would not keep him because he is incurable. I went to work when I was ten years old to support my mother, who was helpless and bed-ridden from rheumatism,” Miss Maxwell said in a sad, low voice. “She was my charge for the twelve years which she spent in her bed. Her death did not free me, for a short time before my brother has been taken to the hospital with the same disease. My mother was hardly buried when he was discharged incurable. There was no one but myself to care for him, so I took him, and it is now seven years since he left his bed, and in all that time he has been my charge. His disease at last affected his mind and has run into consumption. When he dies I will be too old to marry and too old to go into a factory to work.” And the tears would come to her eyes though she bravely tried to smile.

A little woman whose face had wasted away until she was nothing but great black eyes and a hollow cough came in gasping for breath. She sat down, unable to speak.

HOW SHE KEEPS THE FIRE BURNING.

“I’ve had no fire for several days,” chanted Ann by the heater. Somehow she reminded me of the raven above the chamber door. “My daughter works in a store, and it takes her wages—$3 a week—to dress her. If she don’t dress well she’ll lose her place. If it hadn’t been for Mrs. O’Donnell I could never have lived this long. I pray God’s blessing on her every day and night.”

“Have you got any coal yet?” the matron asked.

“I hadn’t money enough to buy a pail of coal. It costs 15 cents; but I bought a pail of cinders from the Italians for five cents.”

“Where do Italians get the cinders?” I asked.

“They gather them out of ash-barrels and then sell them at five cents a pail.”

“Did you get any stockings for me yet?” piped up the woman with the great eyes to Mrs. O’Donnell.

“Not yet. None have come in. How are you feeling?”

“Very much worse, and I have no under-clothing and the cold makes me worse,” and she broke down coughing again.

I stayed at the Diet Kitchen until I was heart-sick with the world’s misery, and then, following Mrs. O’Donnell suggestion, I made a list of several patients and set out to visit them.

First I want to see a blind woman, Mrs. Ellen Nugent, at 76 Mulberry street. It was a high tenement, with narrow, dark, uncarpeted stairs that wound round and round to the top. On each floor were four doors to as many rooms for as many families. I knocked on one door after another, and dark Italian faces glanced out at me, and in reply to my questions said that they did not understand English. At last one woman made me understand that there were no English people in the house except one family on the top floor. When I reached that place, wading through all the débris in the hallways, I wondered how I would ever get out. I knocked and the door was slightly opened. I asked if Mrs. Nugent lived there, and the woman said she did, but did not offer to let me in until I said that I was from Mrs. O’Donnell. That opened the door for me and I went inside. It was a little room, with a small, fireless stove, a few broken chairs, a table and an open cupboard that had a hungry look. A few colored prints of a religious character were hung on the dirty walls, and the ceiling was low enough for me to touch without getting on my tip-toes. A large woman was attempting to set a few dishes in order in the cupboard.

THE EXTREMIST POVERTY.

I stepped softly into the small room. I cannot describe it. The ceiling almost touched the head of the bed and the plastered walls had never known a finishing touch or paper. Bundles of rags and worn bed-clothing lay in the only corner. The only light came through one pane of glass about six by nine. On the bed, amid feather bolsters and some dirty sheets, lay a little old woman with a baby-white face and snow-white hair. She raised herself on her elbow and turned her sightless eyes toward me.

“Mrs. O’Donnell sent me to see you,” I said by way of explanation as I pressed the wrinkled old hand held out to me.

“Heaven bless her; she is so good and kind,” she answered, in a strong, clear voice.

“How did you lose your eyesight?” I asked.

“It came very strange like, about fifteen years ago, when my husband owned a little store. One day I started out to cross the street—my eyesight was as clear as anything that morning—and a green color came before me, so I turned back and went into the store. Then everything was black. My husband took me to a doctor and he examined my eyes, but he said nothing could ever be done for them. I would be blind all my life. Then three years after that my husband died, and all my acquaintances forgot me and I was alone—alone in the world and blind. I hadn’t one friend, one relative, nor one acquaintance to go to. I moved into this house, and for eleven years I have never been out of this room. I am away in the eighties, and for seven years my back has kept me in this bed.”

“How do you get enough to live on and pay your rent?”

“Sure, and she has no appetite. For four years she has lived on the milk which Mrs. O’Donnell gives her. She hasn’t tasted anything else,” said the woman outside.

“That is Mrs. Bagner,” explained Mrs. Nugent. “She is not a relative of mine, but she has been kind to me. She had rooms in this house, but work was so scarce, and her husband is too sick to work, and she has her grandchild to keep, so she moved in here and takes care of me. We pay $7 a month for these two rooms. The Blind Society gives me $40 a year and Mrs. Bagner makes up the rest for the rent.”

“Do you ever have any one to read to you or to visit you?” I asked the old blind woman.

PRAYING FOR DEATH.

“No one but Mrs. O’Donnell. I am always lying here alone, and Mrs. Bagner has to go out to work all day. We have had no fire for several days now, because Mrs. Bagner had no work. Ah! the ways of God are so strange. For fifteen years I have prayed night and day to die. So many strong people, and happy ones, and young ones have been compelled to go in that time, and here I lie begging to be taken away.”

“She spends the whole night praying to die,” Mrs. Bagner called in.

I bought them some coal, and left.

My next visit was to No. 86 Mulberry street. I went through a narrow, cobbled court and up darker and dirtier stairs than I had yet seen. I went to the top of the house, asking at every door for Mrs. Healy. All the occupants were Italians and could give me no information. When I turned to go down the stairs some boys above amused themselves by throwing pebbles and cinders after me, but I kept close to the wall and hurried on. I stopped in a small candy store underneath the tenement and asked the proprietor for Mrs. Healy.

“Go to the rear house an’ you’ll find one room with a lot of widows in it, an’ I s’pose she’s among ‘em.”

A STRANGE EXPERIENCE.

When I explained further what I wanted I was told that Mrs. Healy had a small bank account, and her two daughters were tearing one another’s eyes out to see who would get the money when their mother died. Through the court and filthy back yard I went, and felt my way up the dark stairs and brought forth several Italian families. At last I found Mrs. Healy’s.

A small Irish woman opened the door, and when I asked where Mrs. Healy was she pointed to the side room. I walked to the door and looked in, and as I had had no luncheon and it was past 1 o’clock I felt my spirits weaken. Two beds had been set up in the room, which left a space about two feet square near the door. The only light came through this door, and by its dim rays I saw two of the filthiest beds I ever gazed upon. A gaunt, ghastly form was propped up on one. As I stepped into the little square the form raised itself to a sitting position and stretching out long, bare, bony arms and claw-like hands to me. The woman made some of the most agonizing sounds that I ever heard. I looked at her, and as my eyes became accustomed to the dim light I saw splotches of blood on the death-like face, the wide, staring eyes, the straggling gray hair.

“What is the matter with your mother’s face?” I asked.

“You see she is alone all day, except when I can come to her, and I have a house of me own to look after. Me sister is a widow an’ she works out by the day, so me mother is locked up here alone. Somehow one day she fell out of bed an’ the people next door heard her moaning, an’ when they came in she was lying with her feet in bed an’ her head on the floor, an’ her face was all scratched full of blood as you see it.”

“As you have a home, why don’t you take your mother there and care for her?” She entered into a long explanation about her refusing to keep her husband’s mother, and now he would not keep hers.

“I wish God would take her, bless his holy name,” she whined. “She is a burden to me an’ to herself an’ I wish God would call her, bless his holy name.”

“What does she have to eat?” I asked, shortly.

“Only the milk from the kitchen, and sometimes I bring her a bit of tea meself.”

“Why don’t you use the money she has in the bank?”

She looked at me in a startled way and then dropping her eyes whined:

“She hasn’t much, God knows, blessed be his holy name, an’ she’s a saving that to bury her when God calls her to him.”

A SAD PICTURE OF SUFFERING.

I visited several other old women and divided my little with them. I was called names by young women who were parading the streets; I was hooted at for “a lady” by rude children, and a “Gospel slinger” by others. Altogether my life was made miserable while I investigated Hester and Mulberry and Mott streets. My last visit was a very sad one. It was to Mrs. Siffert, at 137 Mott street.

It was the old, old story. She has two little rooms, for which the rent is paid by kind neighbors. In the front room are two little children—Willie, six years old, and Frances, four—and in the back room, with the seal of death on her quiet face, lies the widowed mother, with her white lips stained with the blood which surges up every few moments from her wasted lungs. The two innocent children talked and laughed together while the mother wiped the blood from her lips and talked to me.

“Four years ago,” she said, “my husband died and I went to washing to keep the children. Frances was born five months after her father died. I was always well and strong until one day I turned from the washtub to have a hemorrhage. That was seven months ago, and ever since I have been in this bed. I know it is consumption, although the doctor does not say so. Since yesterday I have been coughing blood. The neighbors are very kind and see that things are cared for. The kitchen furnishes me with milk every day, and we live on that; but I have such an appetite,” and the strangely bright eyes glance up to me with a smile. “Isn’t it strange? I am hungry all the time and the milk does not satisfy me. I feel I could eat anything.

“The children will have no Christmas,” she continued, glancing out at her little ones. “They do not understand. You wonder why I do not send them to a home? Think how many years they will have to be without a mother and what a little time I have to be with them. I cannot let them go until it is all over with me. If it had only been God’s will to give me strength how happy I would have been to work for them! If it only been his will”—

The poor, wan face turned on the pillow, and several tears trickled slowly down. The children still whispered together in the corner. “Our birdie is dead,” I heard Willie say, and I glanced at the empty cage in the window. Pressing the thin, feverish hand I went quietly out.

Nellie Bly