New York World – December 17, 1894

Nellie Bly Visits Many Miserable Homes Owned by That Corporation.

WRETCHEDNESS AND SQUALOR.

Outrageous Rents for Filthy Dens in Foul, Rickety, Leaky, Unsanitary Hovels.

DEATH, TOO, LURKS IN MANY OF THEM.

You Will Learn Here Something About the Real Life of Dismal New York.

Trinity! Meaning the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. Embracing everything that means love, mercy, justice, charity.

The Trinity corporation is rich beyond the dreams of avarice. It was within its power to solve the tenement-house question, to use its vast wealth to benefit the poor, but what has it done?

I will tell you.

They have been spending thousands of dollars to celebrate Christmas, ordering masses of green foliage and holly and mistletoe to delight the eye, and a special musical programme to charm the ear, while I have been visiting their poor tenants in their miserable tenements.

I happened by chance to go first to No. 4 Grand street. I did not know the part of the city in which the Trinity property is mainly located, and when the Grand street car suddenly swung around a corner and the conductor pointed down a street that stopped abruptly and went nowhere, as the end, or rather the beginning, of Grand street, I was somewhat surprised.

I alighted and walked down the block, looking closely at the houses,. They were small red brick houses, presenting rather a respectable appearance for a poor locality. Near the end of the street I saw a small dilapidated frame two-story and attic.

THE FIRST GLIMPSE OF SQUALOR.

An empty wagon stood in the street and an ash can, overflowing and vile-smelling, was on the shaky frame stoop. There was no number upon the house, and though some inner instinct told me it was the one for which I searched, still I could scarcely believe it. But on looking closer I saw a badly made figure 4 in chalk upon the dirty door.

There was no knob with which to fasten the door, so I entered and found myself in a dark, dirty and ill-smelling hall. The floor was not carpeted, but it certainly was not bare. A layer of filth, the accumulation doubtless of months, covered it.

A knock upon the two doors leading to the rooms on the first floor was not answered, so I went up a flight of rickety stairs, four one way, then a sharp turn and three the other, and I was on a landing from which opened two doors.

I knocked upon the one nearest. It was opened by a little, clean-faced old woman, bent in form and sad of countenance. I told her briefly that I was looking at the Trinity tenements, and with her permission, would like to see her rooms.

The door was opened wide and I was invited to enter. I am used to tenements and sights of poverty, but the picture of misery that confronted me stirred me deeply.

The room was small, about one and a half times the width of a single bed, and one and a quarter times the length. A single bed that crossed two windows just managed to leave space enough for the door to open. At the end of the room and the foot of the bed was a small cook stove. Two wooden chairs, one with the bottom split and the other without a back, and a rickety table completed the furniture. A few ragged clothes hung upon the door, a wooden bucket containing water sat on the floor, and one cup, one plate, a dish and two knives were on the table.

That was all the room contained except three unhappy people—the little old woman, her daughter and her son-in-law, who lay upon the dirty bed propped up against the headboard, for pillow he had none. His face was thin and pale, and his breathing was loud and laborious.

“Are you ill?” I asked rather foolishly, for my eyes had answered my question.

“Yes,” he replied slowly, and in a husky voice, “I had two hemorrhages Monday, and I’m feeling pretty bad.”

I asked him questions, and he told me his story modestly and without complaint. He is a glass packer, but has been out of work for many months, except such odd jobs as he could obtain. Once he carried sample cases for a Maiden lane jewellery drummer. It was during the very cold and wet weather we had a few weeks since. The cases weighed 106 pounds and he carried them, drenched to the skin and shivering with the cold, to Harlem.

ONE TENANT’S MISERY.

That brought on his first sickness. Two weeks ago he got work at No. 72 Murray street at his trade. On Monday, as he left work he had the hemorrhages, and doubtless by the time he is able to go back to work the work will be over for the season, as it is ended when Trinity rings in the New Year.

Still, the man must have shelter while he lives. And although the rain comes in the windows, which are pasted over with paper to do the service of glass, his room is infinitely better than the streets. Cook, eat and sleep in it, for the outrageous price of $2 a week.

There are eight apartments (so called) in the building. One in the basement, consisting of two rooms, for which the charge is $5 a week. The basement is dark, filthy and damp. On the first floor the price for the front room is $2.50 a week and $3 for the rear room. The prices are the same on the second floor, and the hall room is $1.25. In the attic are two pens called rooms for which the tenants pay $6 a month.

The only water is in the yard, a small space, filthy, ill-smelling and filled with pools of stagnant water. The closet, one for the entire house, has no roof and its floor is unsafe. It stands within a foot of the hydrant.

The tenants of the first floor and the basement were out, but on the floor where I found the sick man I saw in the front room an old woman partially paralyzed.

The plaster in the corner of her room was wet where the rain comes through the side of the house. In some places the plastering had fallen down and in all places it was filthy dirty. The floor was warped and uneven.

This old woman is supported by her daughter, a ragpicker who works from 7 A.M. until 6 P.M. for $4 a week, and then, owing to the dull times, is laid off more than half the week.

The hall-room tenant was out, so I felt my way up a twisting and dark stair, so narrow that two persons could not pass on it, and so twisted that I felt every moment as if I would tumble down.

First at the head of five or more steps was a door, a few boards roughly pounded together and put on hinges. It had no knob. No door in the house had. The sick man’s had a nail fastened to a string. Stumbling on a few steps with my head bumping against the rafters, I hit against another door which flies open at my touch and shows me a low and narrow passage with a window at the end, from which a woman is hanging clothes on a line.

She was a nice little French woman, very tidy. Her room, if I can call it such, was merely a little space under the roof.

At one side, where the roof ran up to the rafter, the height was probably five feet. At the other side, where it sloped down, one couldn’t have found space between the roof and the floor to tack carpets. It was practically a case of making two ends meet—the roof and the floor of a house.

A QUAINT ATTIC PICTURE.

There was one window in the place. It was the kind that is cut in the roof and built to stand out. To reach it one would have had to crawl across the single bed, which took all the space, except what was occupied by the wee cook-stove.

It was the smallest place I ever saw for two human beings to live in. But the little French woman had it as clean as a combination of soap, water and hard work can make it, and it wasn’t her fault that the sickly geranium on the window-sill found it always too warm or too cold for health.

As I did not believe in judging the Trinity Corporation by their houses in one street, I decided to make a jump and see if I could not find better ones.

I went to Clarke street and I saw some good buildings that I thought were Trinity property, but when I inquired, I found that Trinity owned the ground, but lease-holders owned the buildings. I was told if I would go further up the street I would find four houses rented by Trinity. They were Nos. 9, 21-1/2, 26 and 28, the oldest, most dilapidated and disgraceful looking houses in the street.

No. 9 is a frame tenement of three stories. It is ready to fall down. The first floor is occupied by a toy and candy shop and is only one room deep. The proprietor lives on the floor above his shop and rents out the top floor for $6 a month. The water is in the back yard, a wet, dirty place, into which the sun never comes. There used to be a frame tenement in the rear, but the Health Board made the Trinity Corporation pull it down.

The floor in the house is anything but on the dead level, and even a short person could without the slightest difficulty touch the ceiling. For this the toy man pays $25 a month, and he thinks it’s not very high, although he has to keep eight black and white cats and one Skye terrier to keep the rats from carrying away his stock.

I went next to No. 28 Clarke street. It is an old frame that bears its misery on its face.

In the basement, where the floor looks like the deck of a ship in a heavy sea, I found a nice old Italian cobbler, with his wife and two children. The old couple could not speak English, but their little boy, with the ideal face of a poet, answered all my questions promptly, intelligently and politely.

THEY HELP SWELL THE FUND.

His father sometimes didn’t earn a dollar in a whole month, he said, but he had two other brothers, one a little bigger than him, who “made ties” in South fifth avenue. The biggest brother had had no work for a long time, but the other brother got $2 a week for stamping the name on “the ties.” His sister worked on “coats,” for which she got $3 a week.

The combined income, $5, had to keep them and pay their rent, $10 a month. Their rooms are three-quarters under the ground and flat upon it.

There is the front and back room, and between is a dark space divided by the passage which connects the two rooms. This dark space holds on either side two beds, which touch the wall at the head and at the foot.

The floor is warped and the walls are damp, but still trinity charges $10 a month for the place.

On the first floor of the house is the same arrangement of rooms, except that the width of the dirty hall is taken from them.

For this front and back room with the dark space between that will and does hold two beds, the family pays $14 a month. The floor in these rooms is worn out, has been many years, but Trinity will not repair it and the family have been compelled to do so themselves.

“The Trinity carpenter said that the Trinity Corporation was like a woman,” observed the girl I found in these rooms. “If she found a small hold she would patch it, but when it gets to be a big one she things it’s useless to do anything and so she lets it go.”

Of course there are many places uptown where for $14 a month this family could hire a four or six room flat, where they would have a bath, range and running water. But they cannot live uptown. Their work is downtown, and they must be near it. The two sons drive trucks when they have work, and the daughter works at feathers, and they together keep the father and mother.

By going up dirty and uncertain stairs, stairs that aren’t mates, or even any relation to each other, I found on the second floor an Italian family that had lived there for twenty-six years. Their rooms corresponded with those below which I have already described. There are no accommodations whatever, unless running water in the hall is considered by Trinity a modern improvement. For these four rooms the family pays $12.50, and the rent has never been reduced in the twenty-six years, although the house has been growing older and poorer all the while.

And never until this month has the family been compelled to ask the wealthy Trinity Corporation to wait for its rent, the woman told me proudly, and she added that they had been very nice about.

Considering that they have paid in rent the entire price of the house, lacking only $6.50, one would suppose the agent might be “nice” about waiting a day or two.

And that is the only thing I found in all my investigation that was “nice” about the Trinity Corporation.

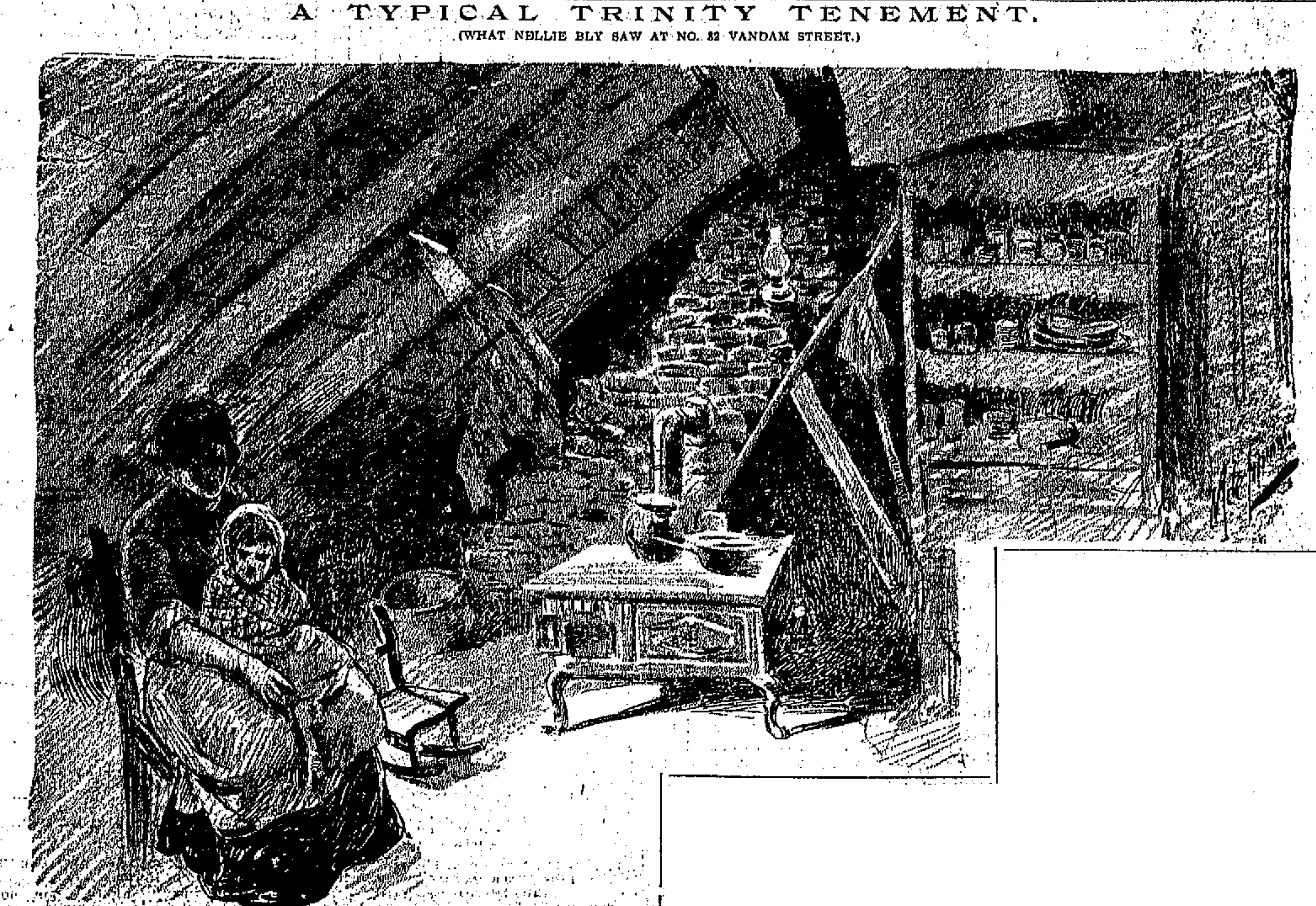

A CRIB UNDER THE EAVES.

On the top floor, if you could ever summon up enough courage to feel your way through blinding darkness to it, you will find a landing with four doors facing each other in space literally not large enough to turn around in.

The one door is from the stairs; the others open into “apartments.” Had I not been told that people lived there I should certainly never have suspected it and never have found them.

As it was I pounded upon the wood I felt in the darkness and a man opened a door and reluctantly admitted me to his home.

I have heard of birds that build their nests under the eaves of houses, but I never knew human beings to have homes there until I visited Trinity’s tenements.

This man’s room was like the one I saw at No. 4 Grand street, only worse. It was smaller and poorer.

A bed stood under the slanting roof at one side; a crib shared the other side with a small stove. Between them was the space of about two feet. It was occupied by a cradle, rather cleverly made of a soap-box, pivoted at either end to two upright pieces of wood. It was certainly not a swinging brass bed, as one sees in the shop windows, but it was built in that style.

The man and I stood at the door. Of course, it was practically impossible to enter the room, or whatever one may call it. We could stand where we were because that happened to be the highest place in the roof, but even a wee baby mouse couldn’t crawl where the roof met the floor.

Still that man, his wife and three children eat, sleep and live in that place. He has not been able to work for many months because he has heart disease, but he can mind the children while his wife goes out to get what work she can—washing, scrubbing, anything—to help make up $4,50 a month so the wealthy and charitable Trinity corporation will permit them to go on living under the eaves.

Trinity has three other “apartments” on this “floor.” They are all like the one I saw, so the man said. One is occupied by an old man and woman, who go out to work every day, and the other is occupied by an old man, who works all day, but, so far as is known, is absolutely alone in the world.

They pay $4.50 for each apartment, which means $13.50 for the floor; $12.50 for the floor below, $14 for the first floor and $10 for the basement, makes in all $50 a month for the miserable old tenement, which is estimated by Trinity as being worth $4,500.

Pretty comfortable interest on their money.

After that I visited a number of Trinity houses. At first I went to some that looked respectable and comfortable, thinking to be able to write that all was not black, but that the wealthy corporation had good as well as miserable buildings for their tenants.

But I was sadly disappointed. Although I spent three days looking after their dwellings in a totally unbiased and conscientious manner, I must state with regret that I soon learned one unmistakable fact:

If a house was painted and had a comfortable look from the outside, it was a Trinity leasehold, and its appearance was totally due to the owner.

On the other hand, if the house was the most dilapidated and disreputable-looking in the entire block, it was owned and rented solely by the Trinity corporation.

Nor did I visit houses in one street alone and base my judgment on them, but made my tour as varied as possible among the houses owned by Trinity in Greenwich Village.

At No. 82 Vandam street I found a miserable two-story and attic frame building, with a collection of poor but interesting tenants.

Going down several steps into a basement that is almost entirely below the street, I found a neat housewife, as I judged by the tidy curtains at the windows.

She had only two rooms, the front one being a kitchen, dining-room and bedroom, and a rear cellar room, the air of which gave me a chill, serving as a second bedroom and containing two beds, which left a space scarcely a foot in width between them.

The poor rooms were as neat as hard work could make them, and the woman was herself as clean as a new pin.

She was such a nice, motherly old lady; the kind that wins one’s heart by a simple glance at her sweet face and white hair, and mild eyes that look straight at one and whose frankness shows that in their whole life they had never one wicked thought or deed to conceal.

I found her in the back yard, vainly trying to pile some good earth around the roots of a tree that had managed to live a starved existence in that poor locality. I love trees as much as I love all dumb animals, and so I naturally felt my heart go out to the dear old English woman.

“Certainly, miss, you may see my rooms,” she said in reply to my inquiry, never asking my object.

And when I had seen them, and she told me the rent—$5.50 a month—and I had involuntarily said something about the outrageous price, she said quietly:

ENGLISH RENTS CHEAPER.

“Do you think that much, miss? I have been told that was low rent for America. We have lived here three years, ever since we came over, and I had no way to know what rent was just.”

“How does your rent compare with your rent in England,” I asked anxiously.

“Well, miss,” she answered, with a smile, “it is vastly different. I only know about Liverpool, where we always lived. We had a nice house there with six rooms; a better house in all, miss, than this, and with it we had a nice garden. For it we paid six six a week, for, you know, miss, we pay our rent by the week there instead of by the month as we do here.”

I asked her how much “six six” was in our money, and she said she thought it was about $1.00.

In this family are the husband and wife, one boy, who “follows the sea,” it being also the father’s trade; two girls and an orphaned niece about fourteen years old. The husband has been unable to work for fifteen weeks owing to a sore leg. One girl lives out, but has no place at present, and the other earns $3.50 a week in a biscuit factory.

There is one other member of the family, a very dear one. It is a green parrot with a black bill and yellow spot at the back of his neck. He calls the nice old lady “Mamma!”, whistles beautifully and sings with a decided cockney accent “After the Ball is Over.”

The floor above this interesting family is divided into two apartments, consisting of two small rooms each. The front rents for $8 a month and the back for $5.50. I did not see either, as the families were out.

From the yard one can walk up a flight of some ten or fifteen stairs to the second floor. It is also divided into two apartments. The front rooms are occupied by a woman whose husband goes to sea. She never speaks to any of the neighbors and has never been known to open her door in reply to any knock. However, all the neighbors know that she pays $7 a month for her rooms.

A little woman with a small baby in her arms admitted me to the rear rooms. The first room is small, and plumes on the hat of a medium sized woman would touch the ceiling.

The room was comfortably furnished, for the family once lived amid better surroundings.

The husband was a longshoreman, or, rather, the employer of longshoremen, a sober, industrious and saving workman. His wife was a neat and saving housekeeper, but exposure to all kinds of weather did its work, and five years ago the husband began to lose his strength.

He held out as long as he could, but the sickness was stronger than he, and now for ten months he has been unable to move from his bed, a victim of consumption.

DYING IN MISERY.

There he lay, a mass of bones covered with a yellow skin. His soul seemed already to have gone beyond, for his eyes were dull and unseeing, giving me the same look of utter unconsciousness that he cast upon his wife and child.

“I have five children,” the woman told me. “The eldest, a girl not yet sixteen, works in a laundry, for which she gets $4 a week. The boy next to her in age is an errand boy and is paid $3 a week. The boy next is at school and the one still younger you see out there in the yard cutting wood for me. The baby (the one in her arms) is not yet ten months old.”

The family lives upon the $7 weekly income and pays $7 a month for their miserable rooms.

I was awfully glad there were three boys. They have to sleep in that bed on the boarded balcony. It must be dreadfully cold, and if it wasn’t that there are three boys and that they have to sleep in a single bed, they would never be able to keep warm. And I am positive Trinity would not give them burial room if they froze to death.

They have to crawl over the foot of the bed to get in. I wonder if they ever laugh, and if they rush to see who’ll get in first, and if they ever tumble each other over the footboard!

Or I wonder if the poor little errand boy is too tired to laugh and play, and if the mother makes the other boys keep still so he can rest, that he may be able to work like a grown man and bring home his poor little $3 every Saturday to help pay the rent to Trinity!

I went up the stairs to the attic. There I found a young widow with two small children. She proved to be one of my human birds, whose nest is under the eaves.

LEAKS! ALWAYS LEAKS!

The roof is high at one side and meets the floor at the other. It has never been boarded over, and the rafters are all black and the light of day shows through the crevices. A stove is fastened to a chimney that goes zig-zag, so that, while it starts near the side of the house, it comes out of the roof at the middle.

When it rains the water comes through on the floor, but the widow smiles as she says it can’t hurt her carpet. She has some bits of worn oil-cloth, but water doesn’t hurt them.

Sometimes the rain drowns out her kitchen fire and that makes her sorry, and when I showed her how wet and damp her walls were she said I must remember that the house must be very old!

She has to go to the yard for the water, as must every other tenant in the house. At night the halls are dark, but in the daytime any one would note how wonderfully clean and tidy the tenants keep them.

For this attic the widow pays Trinity $5.50. She does not complain, nor do any of the others.

I do say, in all my experience among tenements, I never found poorer tenements or better tenants. They are all extremely poor, but they are respectable, clean, and not of the whining, begging class.

An inexperienced person is apt to visit tenements and consider people poor according to their filth. Where they find clean rooms and people they are most likely to fail to note the poverty.

Among the poor in New York I never found as clean and respectable a class as I did in Greenwich village, though Trinity deserves no credit for that.

I next went to No., 88 Charlton street, and I never found a New York tenement so poor. It is a miserable old frame that has stood so many years that it’s too tired to hold up much longer.

On the ground floor is a tailor shop, where a lot of men and women, who pretended not to understand English, sat sewing.

Through the low hall, from which the damp and dirty plastering is hanging, I went up the creaky and unsafe stairs to the landing on the second floor, where I knocked in the darkness until a ragged woman opened a door and let me enter.

She was a poor, miserable, unhappy-looking creature, and was vainly endeavoring to clean a place that can never be made clean.

I never saw walls and ceilings in such a state of filth and dilapidation.

She had this room and one inside that was perfectly dark and had the damp smell of a cellar. The woman made a light and showed me the floor and walls, but the smell was so intense that I asked her a few hurried questions and went away.

A MISERABLE PEN, THIS.

Her husband is at sea, and she has been compelled to put her two boys in a Catholic home. Her girl, not yet sixteen years old, earns $4 a week in the Empire laundry, and on that they live, unless she happens to get a day’s scrubbing.

She pointed to a hole in the ceiling where the plastering had fallen down, and she told me that she paid $8 a month for the miserable pen.

“I think it’s a little too much rent,” she said, timidly, “I don’t think it’s worth more than seven. The halls are dark and filthy, and you should see the yard! We have to carry out water up from it, and it’s awful. I do think the rent’s too much. It’s all poor people can do to pay it.”

I asked her what she knew about the Trinity Corporation—what it meant.

“They’re landlords, that’s all I know,” she answered, which amused me very much.

Next door I found a man and two small and very dirty children in two rooms that beggar description. The filthy and falling walls, the uneven and broken floor, and glassless windows, I leave to the merciful imagination of my readers, who, if curiosity is strong enough, can visit the place.

When I spoke to the tall, dirty man he set the baby he held in his arms down on the floor, and pointing to his mouth, made signs that he was dump. I wrote on a bit of paper that I was looking at Trinity’s tenements, and asked him how much rent he paid. He wrote in reply: “Eight dollars a month.”

I shrugged my shoulders in disgust, and he held up his hands pitifully and helplessly.

I then wrote the following questions, to which he wrote the replies.

“How many children have you?”

“Three.”

“Can you work at anything?”

“I am a longshoreman. No work.”

“Does your wife work?”

“She is out peddling lace.”

RICKETTY AND FOUL-SMELLING.

Just them a pretty little girl not more than five years old came in with a loaf of bread under her arms. She said the man was her father, that her mother talked to him with her fingers, but she couldn’t say much to him. She tried, moving her lips and her little thin arms, but he failed to understand her.

At No. 35 Watts street I found the front house is rented by a respectable widow, who pays Trinity $40 for it and sublets to tenants.

I also learned by this time that many of the Trinity houses are like the corporation—they present a good front.

Many of their old houses have a brick front, which, being painted, is apt to make a casual observer consider the houses very comfortable ut a glance at the miserable frame rears dispelled this delusion.

The rear of No. 35 Watts street is worse even than the yard house back of it, though that is bad enough, It is the only yard house the Fire Commissioners left standing. A short time ago every one of Trinity’s houses had houses in the rear.

In this rear house are two apartments on one side, consisting of two wee cubby-holes, for which the family on the first floor pay $6 a month and the one on the second floor pay $9.

On the next side the apartment on the first floor consists of one room, for which $5 is paid, and on the second and top floor is a room the shape of a flatiron, and scarcely larger, with a small adjoining closet that Trinity calls “room,” for which $5 is paid also.

MISERY PAYS THE TOLL.

The walls and plastering are in a frightful condition. The water is in the yard.

The front and rear houses are estimated at $6,000. The rent collected by Trinity for the same is $85 per month.

No. 259 Houston street is estimated at $5,000 value. It is one of a long row of Trinity houses, but all the others are leased to tenants who sublet. No. 259 has always been leased, too, but the policeman who had it last said he could not make it pay and gave it up.

Two nice old women with snow-white hair live in the basement. They have been tenants of Trinity for the last thirty years. They keep their two basement rooms spotlessly clean and tidy, and it is entirely due to them that the paper on the wall is new and clean and that the ceiling, just an inch or so above our heads, is whitewashed.

But they cannot prevent the floor from being on the slide, nor can they stop the green mould from coming on the damp walls in the hallo, or the green moss from covering the stones in the areaway.

When it rains the water forms in deep pools in the areaway and they have to dip it out, but still Trinity charges them $5 a month for living there.

The first floor has a front and a back room, with two dark rooms between, for which Trinity receives $15 a month. Eighteen dollars a month they get for the second, and the top is divided into two apartments, consisting of two rooms each, for which Trinity receives $9 from each family.

The widow in the rear top rooms is to be dispossessed. She has a boy who used to earn something by “putting in” coal, but he’s been in the hospital for weeks now with spinal trouble. She has two girls. One scarcely twelve was a nurse in some family, but she is homesick. The other girl, a tall, thin, underfed soul, who was frying some foul-smelling fish, said she worked in a candy factory for four years. She used to earn as much as $4.50 a week, but work got slack and slacker, and now she has none at all.

That makes $60 a month Trinity receives on a $5,000 house. The majority of the other homes in the block are leased yearly for $66 a month.

I called at scores of other houses, but as the story of them is the same as that already told of others, I shall not enter into a description of each one. In the rear of No. 12 Clarkson street I found some interesting people. I first looked at the dirty yard and cellar, there being pools of water standing in each.

Then I went in to see the tenement. It and the adjoining one, No. 10, have four floors, with two families to a floor. The halls are narrow, dirty and dark, and the apartments consist of one front room and one small pen dignified by the name of bedroom. Both houses are as filthy and damp as can be imagined, and there is much sickness among the tenants.

The same scale of outrageous prices are charged. For the ground floor $10, $5 for each apartment; $11, or $5.50 each for the second and third floors, and $9, or $4.50 each, for the top floor.

THE CEILING IS FALLING.

On the second floor I found a woman who has lived there for seventeen years next June. Eight years ago her husband died and left her four children to provide for.

She succeeded beautifully. There is no water in the house, but every day of her life this energetic woman carried enough water up from the yard to do a washing. The clothes she had to dry in the one room in which they lived, as the bed fills the other.

Now she does not labor so hard, for one girl lives out, another is a “saleslady” (the mother tells me with pride) and the boy is in a grocery, leaving the little girl at home with her good mother.

In all these seventeen years Trinity has never done any repairing for their worthy widow tenant. Once she papered the rooms herself, but they are in very bad order now, and the ceiling is coming down. The first year after she moved in Trinity reduced the rent to $5, but the next year it was raised again to $5.50, and has remained at that ever since.

In one apartment on the top floor I found a tall, sickly looking man frying fish. A shapeless woman with an appealing look upon her face sat watching him.

He showed me the rooms, keeping a careful eye on the fish meanwhile, so that it might not burn. The walls in the bedroom were wet and the roof leaked in the other room.

The man told me that he used to be a boilermaker in the navy-yard, but his health failed and he was unable to work at his trade and was forced to do odd jobs when his health permitted. He has just returned from ten weeks spent in St. Vincent’s Hospital.

I asked him what was wrong, and the shapeless woman in the chair answered for him.

“He’s got the dropsy, poor dear,” she said, the tears rolling over her cheeks, “an’ they took twenty-six quarts of water from him in the hospital. I’m dying with the same thing. Look at my hands and legs! See, they ain’t any shape to them. I sit here all the time waiting to die. I can’t lie down in bed, ’cause I choke. An’ I haven’t a friend in the world. I’m no kin of his, but him an’ his wife took me in. They’re good, and they deserve better luck than sickness.”

I asked the man how they managed to exist, and he said his wife worked in Gordon & Dilworth’s factory for seven cents an hour. She works ten hours a day, which means 70 cents, and would gladly work longer if her strength permitted.

The man told me also that when he moved in the rooms were so filthy that he had almost concluded not to take them, but the Trinity agents said if he would clean them himself they would allow him for it. But they have never done so, though he papered and whitewashed. They have even refused to pay for the lime.

On the same floor with him is a widow whose sole support is a boy who earns $5 a week in a cracker factory. The woman has “rheumatics so bad she can’t touch the floor.”

Her daughter, about fourteen years old, does the housework. The widow says she has lived there for fifteen years and has never owed Trinity until this month. She is back one dollar, and she sent her daughter out to pawn some clothes so she can pay that.

And this is only part of my experiences among the Trinity tenements.

Nellie Bly.