Girls of the Wild West

Sunday, July 8, 1888

Nellie Bly Goes Down And Makes Friends With The Riders

The Lassies of the Show Are Just Like Nice Girls Everywhere—Miss Hickok Has a Bridle Made from Hair Taken from Scalped Indians—How They Learned to Ride and Shoot Out West When Young.

hew! But can’t they ride? Buffalo Bill removed the gray sombrero from his handsome head in languid surprise, quite English, while I explained that I didn’t want to see any cowboys—although they are a jolly lot—or red chiefs in green paint, trousers and rooster-tail crowns, but just the women folk. He did not object. He said he would be pleased to present me to them as soon as they came off. Just then Nate Salsbury, a hundred handsomer since his marriage, loomed in sight and proffered to relieve Buffalo Bill of the task. We “juked” under the rope which enfences the camp and wandered down to the white tents where live the girls I sought. They were having a little meeting under one of the big trees, and so when Salsbury said: “Ladies, this is Miss Bly, from The World,” I just blushed and said, “Ladies,” and wished I had a plate of cream, a palm-leaf fan and a fizzing soda. “Won’t you come in and sit down?” one said kindly, and we all followed her into a tent on which was printed in big black letters “Lillian Smith.” We talked about the weather and the recent rain and then one excused herself in order to change her habit, she said. Two more wanted to fix up, so I was left alone with two.

hew! But can’t they ride? Buffalo Bill removed the gray sombrero from his handsome head in languid surprise, quite English, while I explained that I didn’t want to see any cowboys—although they are a jolly lot—or red chiefs in green paint, trousers and rooster-tail crowns, but just the women folk. He did not object. He said he would be pleased to present me to them as soon as they came off. Just then Nate Salsbury, a hundred handsomer since his marriage, loomed in sight and proffered to relieve Buffalo Bill of the task. We “juked” under the rope which enfences the camp and wandered down to the white tents where live the girls I sought. They were having a little meeting under one of the big trees, and so when Salsbury said: “Ladies, this is Miss Bly, from The World,” I just blushed and said, “Ladies,” and wished I had a plate of cream, a palm-leaf fan and a fizzing soda. “Won’t you come in and sit down?” one said kindly, and we all followed her into a tent on which was printed in big black letters “Lillian Smith.” We talked about the weather and the recent rain and then one excused herself in order to change her habit, she said. Two more wanted to fix up, so I was left alone with two.

“Tell me all about yourself, beginning with your name,” I said, generously, to the one nearest the entrance.

“I don’t think there is much to tell,” she replied, taking off her sombrero and displaying a handsome lot of auburn hair. (She rides a sorrel.) “My name is Mrs. Georgie Duffy.”

“Where are you from?”

“Wyoming.” She crossed her feet, displaying a pair of jaunty, high-heel boots.

“How did you learn to ride?”

“I always knew how to ride; I never learned.” This was not encouraging. “How did I get with Buffalo Bill? Well, he was traveling out our way and I heard he wanted a rider. He had none then, so I went to him and he gave me a place. For two years Della Farrell, the young girl who has just gone out, and I were the only riders with the Wild West.”

“Of course, you like riding?” I half asserted.

“Yes, I like it,” she replied, warmly. “Well, I wouldn’t do anything else. I don’t call this riding, going around a ring. Out home, where we used to canter for miles through the country, is what I consider riding.”

“How much do you do here?”

“I have the race with Della Farrell, and then I ride in the dance. Twice a day I do this; that’s all.”

“Does nothing ever happen?” I asked, half desperately.

“No, indeed. I think it’s a tiresome world; it’s all the same. My husband is one of the cowboys. He joined the show when I did. Any children? No, thank heaven.”

Mrs. Duffy put on her sombrero and went to her tent, so I turned to the hostess. She was bright-faced, clever girl, and her fingers nimbly constructed a thread lace while she talked with me. She understood what I wanted without making me ask questions.

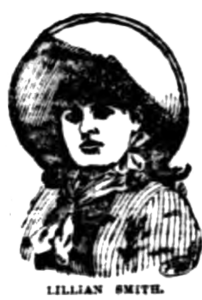

“My name is Lillian Smith. I do the shooting,” she said in a pleasing, unaffected way. “This is my house.”

“My name is Lillian Smith. I do the shooting,” she said in a pleasing, unaffected way. “This is my house.”

“It is quite pleasant,” I replied, as I surveyed the neat interior. Over the entrance was draped a mosquito netting, which gave a certain privacy to her tent, although it did not keep out mosquitoes. The place literally swarmed with them. The white sides of the tent were relieved by dozens of photographs of Miss Lillian’s friends. A centre table, some soft rugs and easy chairs gave a very cosy and homelike look. In the rear was her dressing and bed room.

“I see you have a mirror, anyway,” I said, noticing the large one above a table.

“Yes, that’s the one thing I can’t do without,” she replied with candor; “I always want to be sure my dresses are on straight.”

“It is not strange that I should shoot,” she said, dropping her knitting for an instant to kill, with a sound smack, a mosquito that was imprinting a kiss on her round cheek. “I was born in Coalville, Mona County, Cal. My father was a trapper, or hunter, as you may call him. He shot game for the market. The only other child—my brother—was ten years older than I, so you see I had to find some amusement to fill the place of playmates. My father gave me an old rifle and taught me to shoot.”

“What did you shoot at—marks?”

“First at game,” she replied, turning in place a gold watch bracelet, “and then at balls in the air, as I do here. After one month’s practice, when I was but eight years old, I broke 323 glass balls without missing, and out of 500 I only missed five. That’s my dog,” she said, referring to an exquisite little dog terrier that came nosing around me in a friendly way. “I brought her from England with me. Her name is Beauty. I brought two other dogs—a Scotch collie and a Hardale terrier. They are out in the stables.”

A young Indian lad in gay attire came quietly in and seated himself as if very much at home. He listened to us with dark eyes wide open.

“How did you get before the public?” I asked, while I quietly murdered a mosquito that had tested the thickness of my unfinished kid.

“I got quite a local reputation and one day my father met the manager of Woodward’s Garden, San Francisco, Cal., and he offered me an engagement. I was to give two exhibitions a week for $100, and in all I was to give seven exhibitions. I was only nine years old then and had never been in a city in my life. The largest crowd of people I had ever seen at once time was composed of six people; imagine, then, what must have been my feelings when 7,000 people witnessed my first exhibitions and an increased number those following. Afterwards I travelled with my father, giving exhibitions, until I came with Buffalo Bill. Does it pay? Well, I should say so.”

“Have you never shot yourself?” I asked after she had called my attention to her gun-rack, holding a half dozen rifles, in the corner of the tent.

“My rifle has never gone off accidentally, which is due to the fact that I was taught rightly at first. You see that rifle?” pointing out one not remarkable in any way. I gazed at it steadily. It did not go off. I replied that I saw it. “Well, in London the Queen called me to her and asked me my age and how I liked to shoot, and then she held the rifle, saying, ‘This is quite a heavy rifle.’”

There were no finger-marks on it.

“I own a horse also,” she continued. “He is the only horse in the world, I guess, that has a mane the whole way down his spinal cord. I call him Nigger. Yes, I like to ride, and do quite a lot of it for pleasure. Do we ever get letters from mashers? Well, rather. I got one from a policeman in Newark last week. None of the girls with this show ever care for such things.” Miss Smith is the wife of Jim Kidd, the cowboy.

“Come in, Miss Bly, and sit down,” said pretty Della Farrell, as she held open her mosquito-bar portals. “Bessie will be here in a moment. Take off your hat and be comfortable.”‘

“Come in, Miss Bly, and sit down,” said pretty Della Farrell, as she held open her mosquito-bar portals. “Bessie will be here in a moment. Take off your hat and be comfortable.”‘

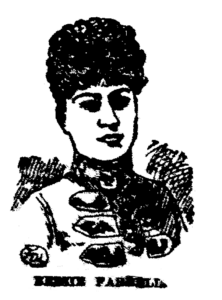

Della Farrell, the young girl who rides the race with Mrs. Duffy, is quite pretty. She had her slender, girlish form tastefully clothed in a white-embroidered blue dress. Her large, blue eyes with long, curled lashes, gaze on one with a truthful, frank candor, and her wavy brown hair, which hangs in artistic looseness around her head, is charming. In the V-shaped vest she wore several gold medals which she has gotten by winning races. One, especially pretty, given her during her first season, is engraved with herself on horseback. Just then Bessie Farrell came in and we all went into the room at the rear of the tent, where it was cooler.

“I could not say when I rode first,” said Della. “I have been riding ever since I can remember.”

“We were born and raised in Denver, Col.,” said Bessie, with a smile. “There were our father and mother, our brother and we two girls in our family. We always had lots of horses and, children-like, we were always romping with them. We were never taught to ride, but just hammered it into ourselves by hard experiences, which is the best way after all.”

“I was never inside a riding-school,” said Della, looking up from the popcorn she was dissecting, “and from what I have seen of women who learn riding so I think it better to learn outside.”

“Della learned outside,” Bessie said with a laugh. “We had a pony”—

“Dolly was its name,” Della interposed, with her mouth filled with popcorn.

“And we children always fought over it, rode it turn about, or stole it from the other,” Bessie continued, “just as children will. We had our own saddles and bridles, that’s one right we religiously kept. I never liked horses half so well as Della did, but I had a mania for stealing away—when I got any money—and hiring a horse from some stable.”

“We never used riding habits,” said Della. “We just jumped on and rode in our short skirts. If we had learned in long skirts we would never have lived to give exhibitions.”

“No, I should say not,” Bessie said, as she vigorously used her fan. “Dolly ran off with Della at last—(“She was a little divil,” from Della)—and so father sold her, because Della was badly hurt.”

“No, I should say not,” Bessie said, as she vigorously used her fan. “Dolly ran off with Della at last—(“She was a little divil,” from Della)—and so father sold her, because Della was badly hurt.”

“I had the worst old saddle,” explained the charming Della. “It only had one horn.”

“We would never have been in a show,” said Bessie, “if old Dave Cook, the great Rocky Mountain detective, hadn’t told at our house one evening that Buffalo Bill was in town and that he wanted a lady rider for his new show. Della got wild to join him—(“I had to coax a long time before my mother would consent,” said Della)—and she went down to the theatre and made an engagement with him. Then I came on and joined them at the Madison Square Garden. It is not hard work, and the pay ranges from $50 to $100 a month, with board.”

Bessie Farrell is quite as nice as Della. She wore a black lace skirt, a cambric blouse closed with gold buttons, a pretty pin, several handsome rings and a large white hat covered with red roses. She has blue eyes, light hair and a lovely expression. I bade them good-by and went to see Miss Emma Hickok, who does the fancy riding, making her horse go through all sorts of movements at the touch of her whip.

Her eyes are dark and her hair, which is short and curly, match them in color. She is rather petite. She wore a white lace dress, caught at the throat with a handsome pin and at the waist with a dozen silver pendants, even as the fashionable women of to-day carry. Heavy silver bracelets encircled her wrists and her fingers glittered with costly rings. Her tent is quite handsome and two vases of fresh flowers enhanced the whole. She is always at ease and did the honors of her little home in a pleasing manner.

“My life has been spent among horses,” she said. “My father was a famous horseman and since I can remember I have known how to ride. I was born in Cincinnati, but I can’t say that I belong to any one place. My life has been spent on the road, so I really have no home. When five years old I began my career as a rider. All I know about training horses I taught myself. Is it hard business? Yes, very. It is dreadful for a woman to keep it up long. Of course I like it, having spent my life at it. The way I got with Buffalo Bill was through my step-father, Wild Bill, who was once Col. Cody’s partner. The work I do now I call rough work. I don’t do any fine business. The big bay which I now ride I only rode three weeks before we arrived in London. I call him ‘Caprice,’ because he is such an ugly-tempered brute. While in England I bought a little black Arabian horse. I call him ‘Kismet,’ and now have him home with me.”

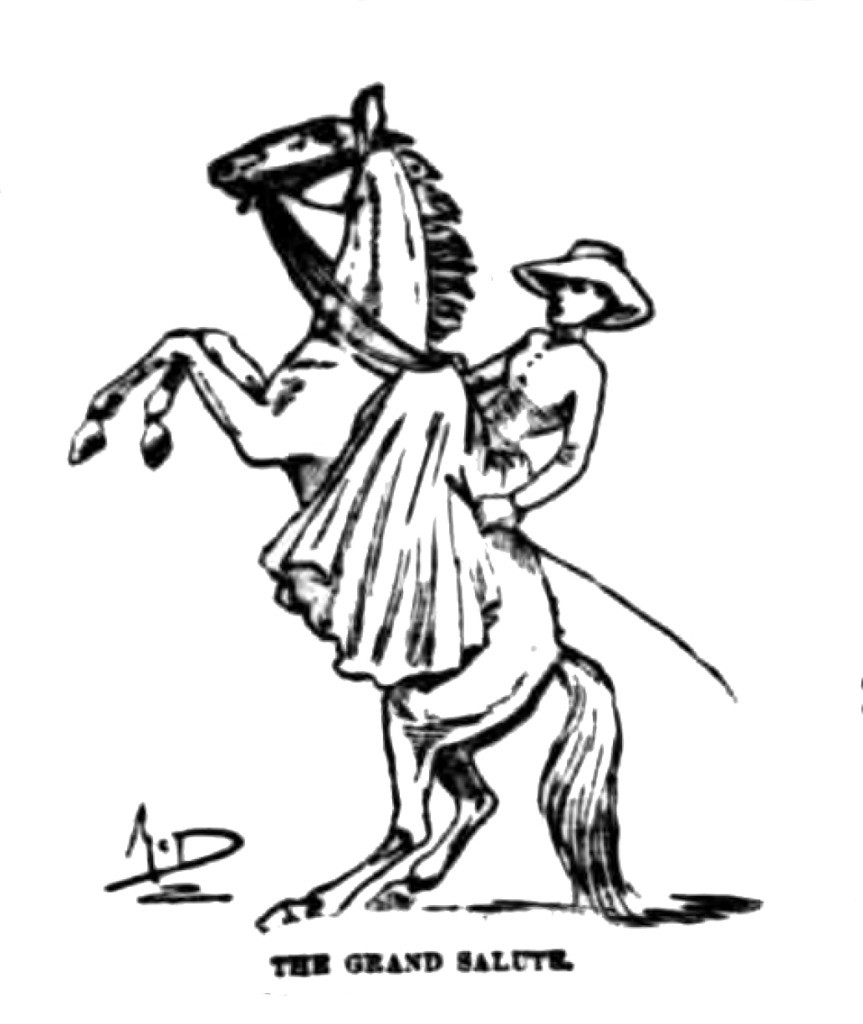

“I notice that you do not use a saddle in your exhibition,” I said. “What do you use instead?”

“I use what is known as a ‘sway.’ It is a pad about six inches wide, and has three horns and a wide girth. My stirrup is a patent one, which I bought in London for a pound. It is arranged so I cannot be dragged. If I fall, the spring flies open and my foot comes out. I always ride with a spur, and I’m the only woman I ever knew who does. You see, if the horse gets stubborn, I have my whip in my right hand and the reins in the left, so, with my spur, I can control both sides. If he jumps one way to avoid punishment he gets it on the other side.”

“I use what is known as a ‘sway.’ It is a pad about six inches wide, and has three horns and a wide girth. My stirrup is a patent one, which I bought in London for a pound. It is arranged so I cannot be dragged. If I fall, the spring flies open and my foot comes out. I always ride with a spur, and I’m the only woman I ever knew who does. You see, if the horse gets stubborn, I have my whip in my right hand and the reins in the left, so, with my spur, I can control both sides. If he jumps one way to avoid punishment he gets it on the other side.”

“Why do you use a sway instead of a saddle?”

“Because it is more attractive. It is much more difficult and so, in the eyes of professionals or those who understand the art, my performances are much superior. There is another thing I do which no other woman does. I ride with a stirrup as long as a man’s. Why, because if the third horn should break I am perfectly independent, having firm footing. As an exercise for women nothing can excel horseback riding.

“I want to show you something which has no like,” she said, and, going to the interior, she brought forth a bundle. “When Col. Cody first saw me ride he said: ‘You are the finest rider I ever saw and I will send you the finest bridle I ever saw.’ Several weeks later I received notice that a package awaited me at the express office. It was an exquisite bridle made of finely woven hair, with buckles of solid silver and tassels of hair.

“This is made of human hair,” she said, “from scalps of Indians taken by Buffalo Bill, and the buckles are made from chunks of silver given him at different mines. It is not possible that you will ever see the like of it again. August Belmont, the New York banker, offered Col. Cody $1,000 for it”—

“Break away, thar—break away!” shouted a deep, good-natured voice, and a great, monstrous fellow, stooping almost double, entered the tent. “Break away, now,” he repeated, and I looked apprehensively at the chair he threw himself into.

He was immense! He wore a bright red shirt, crossed at the front with a gold chain heavy enough to tie down an elephant. He removed his black sombrero and tossed back his long black hair carelessly, while he glanced at me with his bright black eyes in a boyish, teasing manner.

“You are mistaken. This is a different lady,” said Miss Hickok, hurriedly, whereupon she added:

“Mr. Buck Taylor, Miss Bly.”

“How du du?” said I.

“How are you?” said Buck.

We smiled and shook hands.

“Now, look here,” he said. “I’m going to kill the next one. (“Please don’t, she may be nicer,” I inserted.) You’re the third that’s come here and talked us to death and we haven’t seen a line of it printed yet. I shall kill the next.”

“What will you do with yourself when the Wild West is no more?” I asked, in order to divert his mind from his murderous threats.

“Go back to Texas.”

“How do you make the un-English Indians understand?” I asked at random.

“Club them into it,” he replied, with a laugh. “Say, why don’t you try to ride one of the bucking horses? Now, that’s what would make a story.”

“But I might get my neck broken,” I protested.

“That’s what would make the story,” he replied, coolly. “Then there would be something to write up.” He followed me out as I started home. I stopped to bid Col. Cody, who was dictating a letter, good-by.

“Come down some day and take a ride,” he said, cordially. “The girls have lots of habits. You look just the right size to ride. I hate these big women who want to ride. Do they? Well, the bigger the woman the worse she wants to ride.”

Nellie Bly